A new analysis by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration shows more vessel operators are abiding by ship speed limits the agency sets to protect endangered North Atlantic right whales from ship strikes along the U.S. East Coast.

A few hours before the agency’s study came out, the environmental group Oceana issued an update in its own series of analyses tracking ship speeds. Its conclusion: far too many vessels are still breaking the recommended 10-knot limit when right whales are known to be in waters near U.S. ports.

Both reports rely on data from Automatic Identification System transmitters carried by most commercial vessels, which record their tracks at sea. AIS is chiefly a safety system – allowing vessel operators to broadcast their real-time positions and see where other ships and boats are in relation to them.

AIS data also allows observers to calculate real-time and past vessel tracks and speeds. NOAA and Oceana used the same data, but different methodologies to draw somewhat divergent conclusions.

For NOAA, its examination of vessel speeds shows improvement since the agency started declaring “special management areas” around right whale habitat and shipping lanes during the 2008-2009 season.

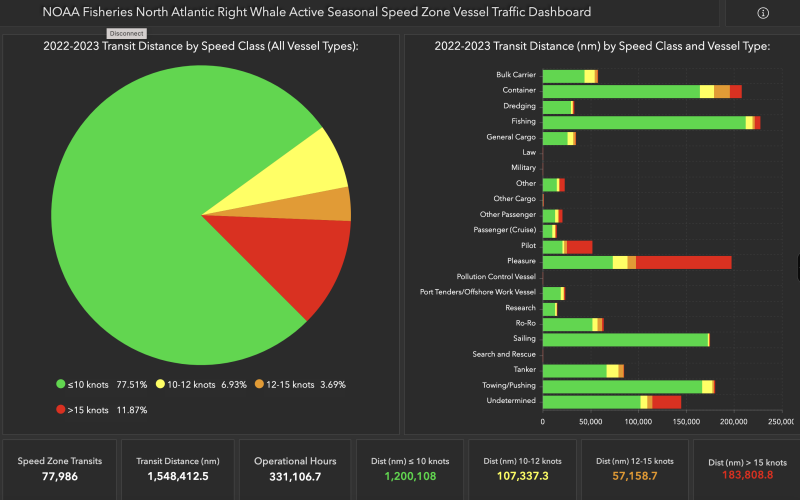

Overall compliance with the speed rule during the first season the rule was in place during 2008 to 2009 was approximately 50%, said Lauren Gaches, a spokeswoman for NOAA Fisheries. During the most recent season in 2022 and 2023 the compliance rate is up to about 80%, said Gaches.

That’s after a stepped-up enforcement campaign by NOAA’s Office of Law Enforcement, which has levied more than $1 million in civil penalties on vessel operators documented to have exceed speed limits in the last two years. OLE officers are using a suite of enforcement techniques, from monitoring vessel AIS tracks through seasonal management areas, to officers on shore and on the water using radar to determine how fast ships are moving.

NOAA has proposed expanding the speed limit requirement to vessels under 65 feet in length – a measure fiercely opposed by the charter fishing industry, recreational boatbuilders and other maritime interests with allies in Congress. Oceana is pushing for faster action on vessel speed limits, and says its new report shows a pressing need for it.

The new analysis “found that 84% of boats sped through mandatory slow zones, and 82% of boats sped through voluntary slow zones. This report, which provides an update from Oceana’s 2021 analysis, shows that stronger safeguards and increased enforcement are needed to save North Atlantic right whales,” the group said in issuing its report.

“If NOAA wants to save this species from extinction, ships must slow down when these whales are present, and speeding boats must be held accountable. Time is of the essence before North Atlantic right whales reach the point of no return,” said Gib Brogan, campaign director for Oceana.

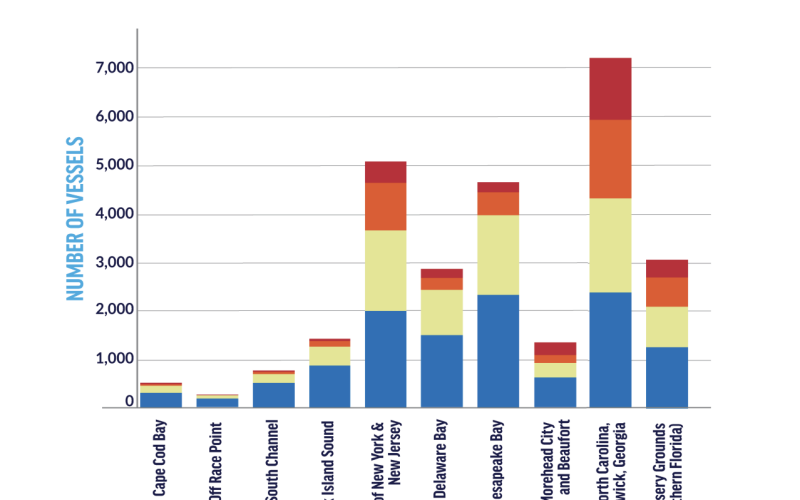

The 2008 rule created two categories of speed zones. Special Management Areas are drawn around areas at times of the year when right whales are known to be using them for feeding, breeding, giving birth to calves, and migrating. Ten SMAs from Massachusetts to Florida require vessels 65 feet and longer to hold their speed at 10 knots or less, with exemptions for safety reasons and federal and state vessels conducting law enforcement or search and rescue operations.

Dynamic management areas are declared by NOAA temporarily for 15 days based on visual sightings of right whales, and operators are asked to voluntarily restrict their speeds to 10 knots on vessels 65 feet or longer.

The NOAA and Oceana reports diverge in the methodology each used to measure compliance with the rule.

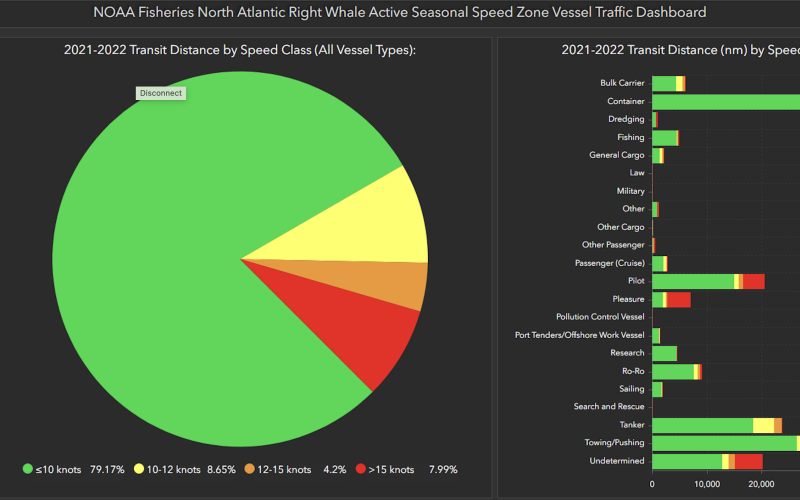

The NOAA findings are presented through a new online digital “dashboard” that allows users to examine vessel speeds in special management areas over time. It provides a summary through 2022-2023. Oceana’s analysis runs through the 2021-2022 season.

While both groups rely on AIS data, “our methods to classify speeding are different,” Brogan told WorkBoat.

“For example, using NOAA’s methodology, there was almost 79% compliance (or 21% non-compliance) in the 2021-22 season in the NY/NJ Seasonal Management Area,” said Brogan, referring to a screenshot image of the NOAA dashboard.

In contrast, “Oceana’s analysis shows a much lower 12.9% rate of compliance during the 2021-22 season (reported in our report as 87.1% speeding on page 18),” said Brogan.

“It only takes one second for a speeding ship to strike a whale. We can’t rely on weighted averages when it comes to speeding,” Borgan contends. “Just like speed enforcement on our roads doesn’t account for the weighted average speed of the car’s trip. You’re either speeding, or you’re not. Speeding at any point in slow zones is dangerous for both the boaters and the whales when they’re in the same waters.”

Both reports will come into the ongoing debate over NOAA’s proposal to extend speed limits to vessels between 35 and 65 feet.

Activists’ case for extending the rule was bolstered was boosted by several incidents, including a 2021 case when a 54’ charter sportfishing yacht headed home to St. Augustine, Fla., struck and killed a juvenile right whale, despite the captain and mate keeping visual and radar lookouts. They barely made it back to the inlet with eight passengers to ground on a sandbar before sinking, a $1.2 million loss.

But there are moves in Congress to head off any action by NOAA, seeking to force a delay in extending speed limits.