Charles Good recounts the moment that quite literally sparked the beginnings of Cox Marine.

The year was 1966. Charles was a 20-year-old aboard his mother’s wooden sailboat, anchored off Greece’s Ionian Islands. He was decanting gasoline into a smaller container when he spilled a significant amount on the deck. Almost immediately, the liquid erupted into flames after coming in contact with a nearby gasoline-powered refrigerator.

Fortunately, the fire was contained, and nobody onboard was injured. Though Good was unscarred, the incident left a lasting impression on him: It was then that he recognized the need to develop an outboard engine using diesel fuel.

“It was obvious to me that the market needed a diesel outboard and has needed it for decades," he said in a Cox Marine web series. "Nobody had done it. And there was a reason for that, it is very difficult to do.”

The difficulty lies in the engine’s weight.

Decades passed, and by the early 21st century a diesel outboard engine had yet to come to market. Good was working at a small investment bank at the time, and the global demand for a diesel outboard had only intensified.

Good remembers a project that kept hitting his desk. A U.K.-based engineer had designed a lightweight idea for a diesel engine. The man behind that project was David Cox, an innovative engineer specializing in engine design on the Formula One automotive racing circuit.

“The thinking behind it was, 'How do you take weight out of an engine?'" he said. "Formula One! There’s no better place to look. They spend a vast amount of money taking weight out of engines.”

In 2008, Good was introduced to Cox and was immediately struck by his innovative nature. To provide some background into the out-of-the-box thinking required to reimagine the diesel engine, a little context on Cox’s resume in the Formula One circuit is necessary.

Around the time Good nearly set himself afire on his mother's boat, Cox was making strides in the auto racing industry. He had designed a turbocharged engine and was offered a job as a development engineer at the British Touring Car Championship. There, he developed several V8 engines, and built the Brabham BT46B fan car: a car that made a name for Cox in the Formula One circuit. This design won its first and only race, as it was ultimately banned in Formula One racing.

Cox's success in the racing circuit, paired with his ingenuity, led to other creative concepts that could not be overlooked. His innovative solutions are recounted in his personally narrated curriculum vitae, which he notes as an unusual method to describe his job history.

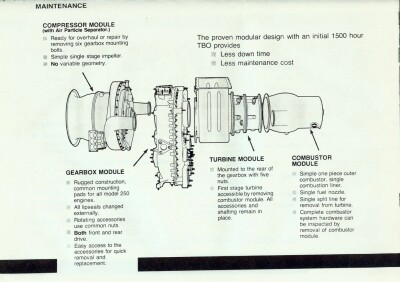

Cox's innovations vary from a 12-wheel race car called the Lion Grand Prix to new crankshaft designs for 6-liter Ferrari Maranello Le Mans engines in cars that won their classes. The last project that he mentions in his CV is his “eureka moment in a small room [which] brought forth the POCOx (Piston Opposed Cylinder Opposed) engine concept” that he had been working on for two years.

It was this project that Cox was working on that made its way onto Good's desk in 2008. Good took the plans to a neighboring engineering firm, Ricardo PLC, which liked a lot of its features. Their intrigue was enough to commit Good and his investor group to back the development of Cox's lightweight diesel into the powerhead for an outboard engine.

The first fire of Cox’s concept alpha engine occurred in 2010, and three years later the engine began its on-water demonstrations.

Cox passed away during the development years, but he was able to witness the test trials of the first diesel outboard, and his idea lives on through the Cox Marine name.

Using his concept as a foundation, Cox Marine was able to build the first outboard diesel engine on the market. The company employs engineers from automotive combustion backgrounds and has hybridized their tecnhical knowledge for marine application.

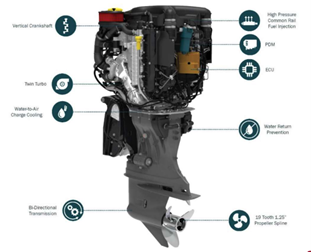

The CXO300 went into production in May 2020 and is becoming increasingly popular. Its technology is confined to the same dimensions as a gasoline outboard but harnesses a diesel inboard's fuel efficiency and reliability.

The same vertical crankshaft architecture is present in both engines.

What makes the CXO300 unique is that it consumes 35-70% less fuel compared with a gasoline outboard, with 44-76% less CO2 emissions.

These features all stemmed from a single idea in a small room by an engineer who pushed the boundaries of the diesel engine.

At his funeral, Coxs's innovative nature was summarized by his friend John Minett. “Someone said to me recently that perhaps David’s ideas should have been locked in a safe and revisited after 10 years to give the rest of the world time to catch up.

“If he had settled on something slightly less ambitious, we could have had it running earlier, and what he saw as engineering compromise was never David’s way.”

.jpg.small.400x400.jpg)