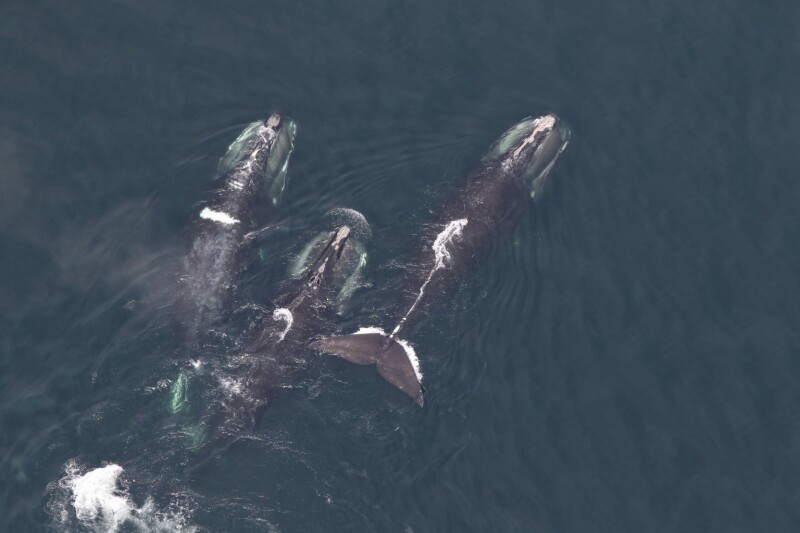

With only around 340 North Atlantic right whales surviving in one of the world’s most endangered species, preventing their deaths in ship strikes is critical, conservationists say.

“Even one human-caused mortality puts the species at risk of extinction,” whale researcher Jessica Redfern of the New England Aquarium warned, as a Congressional subcommittee heard testimony Tuesday on new proposed vessel speed limits to protect the whales.

A rule proposal by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration could extend 10-knot speed limits in areas when right whales are present, and expand the limits to cover vessels between 35 and 65 feet in length. Aimed at protecting the whales, the proposal is seen as a mortal threat by some U.S. maritime groups, from recreational boat builders to charter fishing captains and port pilots.

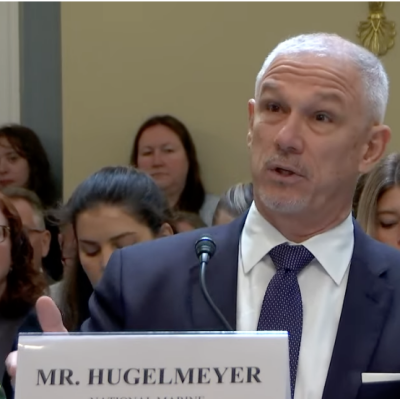

Allowing NOAA to declare 10-knot speed zones would be “the greatest restriction to our nation’s cherished waterways” from Massachusetts to central Florida, said Fred Hugelmeyer, president and CEO of the National Marine Manufacturers Association. Hugelmeyer was one among a panelists of experts invited to the House of Representatives Natural Resources Subcommittee on Water, Wildlife and Fisheries.

NOAA’s proposed “strike reduction rule” is aimed at reducing maritime roadkill. “What makes right whales so vulnerable is they spend so much time at or near the surface,” explained Janice Coit, NOAA’s assistant administrator for fisheries.

“We can’t afford to cause even one more whale death per year, and achieve our conservation goals,” said Coit, whose agency is legally bound to protect the whales by federal laws dating to the 1970s. But Coit also acknowledged NOAA’s plan to extend speed rules is controversial; more than 90,000 comments poured into the agency during a public comment period that ended Oct. 31, she said.

“It is important to emphasize this is a proposal,” Coit told subcommittee members. Meanwhile, the Biden administration this week announced a package of spending goals for ocean issues that will include $82 million for monitoring the right whale population and finding ways to protect them, said Coit.

Hugelmeyer said NOAA failed to engage the National Marine Manufacturers Association in early discussions about the rules, leaving them “stunned to learn” of plans to extend speed restrictions.

In poor weather and sea conditions, mandating 10-knot limits would force boat operators “to risk their vessels and their own lives…at the speed of a bicycle,” said Hugelmeyer.

NOAA’s assessment of likely impacts of the rule on the boating industry is “littered with inaccuracies” including underestimates of how many vessels would be affected, said Hugelmeyer.

Extending speed limits would make the work of U.S. port pilots more dangerous and increase the danger of shipping accidents near East Coast ports, said Clayton Diamond, executive director of the American Pilots Association.

Pilots head out to meet ships incoming to U.S. ports in small, speedy boats, and they need speed for safety when coming alongside ships to make pilot transfers, Diamond explained. Making the ladder climb up the side of a container ship is always dangerous; eight pilots have died since 2006 in accidents during vessel transfers, said Diamond.

A 10-knot speed limit “would make it impossible” for running tuna charter fishing trips, said Fred Gamboa, a captain who operates 39-foot and 44-foot center console boats out of Point Pleasant Beach, N.J.

“We have a symbiotic relationship with whales,” said Gamboa, a 17-year veteran of the charter industry. Whales help lead fishermen to aggregations of fish, and inspire his clients, Gamboa said: “When we see one, it turns a good trip into a great trip.”

But his captains rely on speed for safety, keeping their boats up on plane and watching the sea surface ahead – not just for whales, but drifting shipping containers and other debris common in the New York Bight.

If NOAA imposes a 10-knot speed limit in that region, “it is simply not feasible,” said Gamboa. He’s calculated that his business could be at risk of losing 70 trips in a year, at a loss of $140,000.

Gamboa and other industry advocates said they want Congress to delay any rule adoption by NOAA until new measures can be taken to reduce the danger of whale strikes. There is also apprehension that environmental groups could push NOAA to adopt broad speed limit rules on other U.S. coasts.

“There’s already a petition to NOAA to expand this to the Gulf of Mexico,” said Hugelmeyer. “We expect this to metastasize” with activist groups seeking similar measures on the West Coast, he added.

The group Defenders of Wildlife said extended go-slow zones are one chance to stave off the right whales’ decline.

“We need seasonal slowdowns to protect right whales in danger zones, just like we have lower speed limits to protect children near schools. Slowing down is the best way to reduce accidental collisions and protect both whales and human safety,” said Jane Davenport, senior attorney with Defenders of Wildlife. “NOAA Fisheries’ science-based rule is vital to the survival and recovery of this iconic species."