It will be the rare WorkBoat reader who isn’t familiar with the 2009 seizure of the containership Maersk Alabama. The incident, more often described as a hijacking, took place during an era in which the interdiction of shipping by Somali pirates was a common occurrence.

Indeed, according to The New York Times, Somali pirates operating in the Gulf of Aden that year attacked upward of 214 vessels, resulting in 47 hijackings.

As it happened, the pirates in the Maersk Alabama affair were unable to gain control of the ship and resorted to taking Capt. Richard Phillips hostage, as later chronicled in Capt. Phillips’ memoir as well as the movie in his name starring Tom Hanks.

Phillips would be the keynote speaker at the 2014 International WorkBoat Show.

The incident was also atypical in that it was the first Gulf of Aden hijacking involving a U.S.-flagged vessel.

If the Maersk Alabama episode was unusual, the hijacking two years later of the Brilliante Virtuoso, a Greek-owned, Liberian-flagged Suezmax tanker bound from Ukraine to China, was as bizarre as it was sordid.

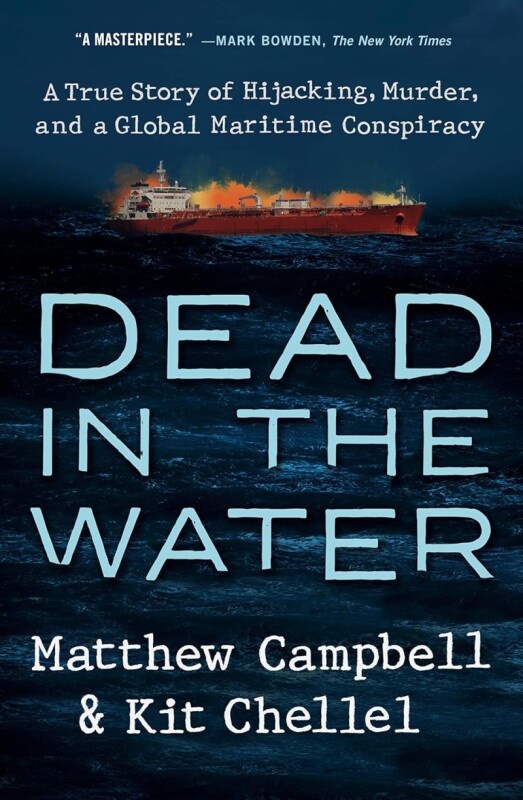

The story is chronicled in “Dead in the Water: A True Story of Hijacking, Murder, and a Global Maritime Conspiracy,” by Bloomberg reporters Matthew Campbell and Kit Chellel. The book represents a monumental reporting effort, yet it is as engrossing as tightly written fiction and very often as hard to put down.

Pirate activity continued to trend upward after 2009, but it appeared that ship owner Suez Fortune, which had yet to spring for a shipboard security team, had a plan to get the tanker through the Gulf of Aden unmolested.

The Brilliante would rendezvous and take a security team aboard on the morning of July 6. No vessel carrying such a team had ever been attacked. To be on the safe side, crewmen strung razor wire from the railings, readied the fire hoses (for blasting any pirates who would scale the vessel’s hull) and placed a coveralls-clad dummy as a scarecrow visible in the stern. They also prepared a so-called citadel stocked with necessities should they need to barricade themselves in a safe redoubt.

On the night of July 5, the Brilliante shut down, presumably to await the arrival of the security team.

Shortly after midnight, seven men wearing camo gear and masks and with Kalashnikovs slung over their shoulders — but no shoes on their feet — arrived by in a small, wooden outboard and asked to come aboard. They assured the Filipino crewman who hollered down to them that they were, indeed, the security team, and on the captain’s orders the crewman allowed them aboard.

It was only moments until the crewman felt a Kalashnikov in the small of his back.

What unfolded was odder still. The boarding party rounded up the crew, who remained under guard. Four of the boarders then set out with the captain and the chief engineer. To the chagrin of the captives, the main engine started. The crew assumed they were en route to Somalia to bide their time amid rats and feces until a ransom deal could be worked out.

Then the engine stopped and the lights went out. There was an explosion. Smoke billowed through an air conditioning vent. When the crewmen tentatively opened the door to get out into the air, the companionway was empty.

The boarding party was gone. The crewmen found the captain but were unable to locate the chief engineer. All but certain he was consumed by flames in the engine room, they abandoned ship; he was eventually spotted waving a flashlight from the Brilliante’s deck. After diving into the sea he was picked up by a helicopter crew from the cruiser USS Philippine Sea.

Although her crew was safe, the Brilliante Virtuoso was burning off Yemen.

In many respects, this is where the story begins. The Brilliante was carrying $100 million worth of oil; the vessel itself was insured for another $80 million — more than enough to attract attention in the hoary offices of Lloyd’s of London.

David Mockett, a British master mariner and marine surveyor who had lived in Yemen for decades despite its increasingly violent political climate, was sent to survey the burned ship, now anchored off Aden. This did not appear to be the work of pirates. He made known that he could not make sense of what he found.

But if this was an inside job, the owner could have peddled the oil in an out-of-the-way port, pocketed that money, then scuttled his ship, collecting an insurance claim as well.

Days after expressing his doubts, Mockett was incinerated in the blast of a car bomb placed under the seat of his car.

“Dead in the Water” chronicles the twin tracks of an insurance fraud investigation and a murder case. Its cast includes characters honorable and dishonorable, as well as those burdened by fear. Actions of the ship’s owner, chief engineer, and salvor strained their credibility.

It is also an insightful look into the world of high-stakes insurance. Founded in a London coffee house in 1689, Lloyd’s is not so much as an insurance company as it is a marketplace where corporations and private individuals come together to collect premiums and spread risk.

Although there may be figurative truth in the notion that city skylines are defined by the towers of insurance companies flush with cash from policyholders who cannot get through on the phone, eight- or nine-figure maritime claims can shake their foundations.