Battered by months of political pressure, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management brought in its experts to appear at a June meeting in Atlantic City, N.J., to explain BOEM’s draft environmental impact statement for the Atlantic Shores offshore wind project off New Jersey.

With posters and graphics, they dealt with residents’ concerns and complaints about how a future seascape dotted with turbines could affect their property values.

Dead humpback whales were another topic, after a months-long barrage of claims that offshore wind surveys might have been a factor in winter whale strandings. BOEM workers talked about survey boats using observers and protocols to avoid affecting marine mammals during geophysical survey work.

“The type of equipment they use for surveying, plus the precautions we have in place, just don’t indicate that that’s a cause,” said Karen Baker, chief of BOEM’s Office of Renewable Energy Programs.

“However, we take it very seriously. All of us are very concerned and impacted by it,” Baker said during an interview at a public information session June 22 in Atlantic City. “You don’t come work for BOEM if you don’t care about the ocean.”

Before joining BOEM, Baker was regional programs director for the Army Corps of Engineers North Atlantic Division from 2019 to 2022, and formerly the Corps’ chief of environmental programs. Living in the Bay Ridge section of Brooklyn, N.Y., along New York Harbor gave her a view of the region’s maritime economy. Offshore wind development adds a whole new dimension.

“I think this is a complex issue. It involves so many different issues. I’ve learned a lot in my year here about what a busy ocean it is and what the competing uses are,” said Baker. “There’s complexity, but a lot of opportunity too.”

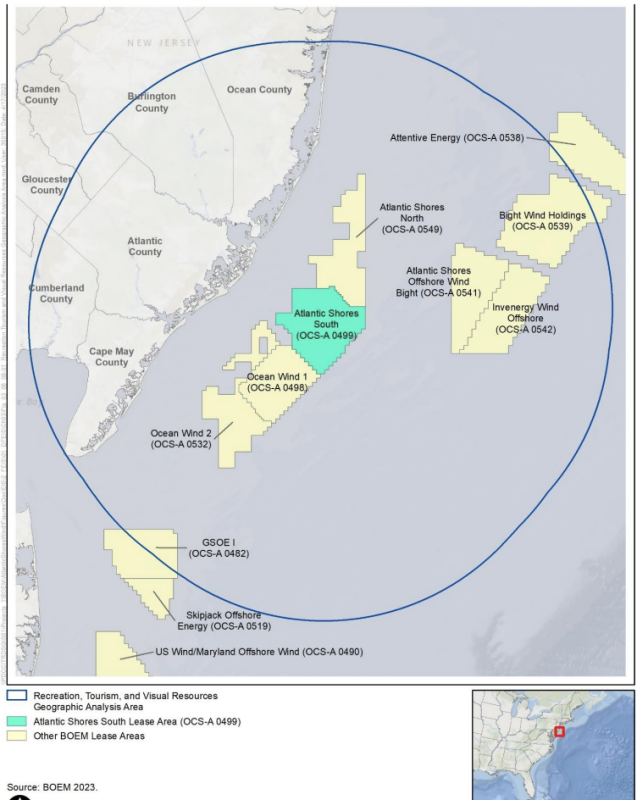

The potential visual impact of offshore turbine arrays has been hitting home on Jersey Shore and New York beach communities as developers publish more simulated digital images. At the Atlantic City session, and another a day earlier in Manahawkin, N.J., seaside homeowners talked about how the Atlantic Shores project would end the clear horizon they cherish.

Some alternatives in the BOEM environmental assessment include possibly reducing the number of turbines to lessen the visual impact.

“I still remain optimistic … even these meetings have given us encouragement,” said Baker. “There’s definitely concerns but there’s still I think a lot of opportunity for us to continue to have those engagements.”

But New Jersey surf clam fishermen say they won’t be able to work in the planned turbine arrays. For years they have sought a two-nautical-mile spacing between turbine towers.

“Our worst fears have been realized and these dreaded exclusion areas will become the norm in the future for the clam industry and other commercial fisheries wherever wind turbines are constructed,” wrote Peter Himchak, a marine biologist and consultant to New Jersey clam companies, in comments to BOEM.

Baker said she could not comment specifically on the clammers’ position. The agency is working “to find mutually beneficial solutions whenever we can,” she said. “I think it’s something we put effort into every day.”

Baker said she’s been visiting with fishermen at docks throughout the region to learn about their concerns. With so much diversity in the fishing industry “it’s definitely not one voice,” she added. “It takes a considerable amount of my time … I’m not complaining about that. It’s important.”

On the West Coast, fishing advocates have raised enough alarm over BOEM’s early plans for wind energy areas that the Pacific Fishery Management Council in March asked the agency for a complete reset on the process. Then Oregon Gov. Tina Kotek and the state’s Congressional delegation likewise asked BOEM on June 9 to pause its planning for more studies. “We’re still reviewing that and considering what the options are,” said Baker.

Meanwhile wind developers’ costs and supply chain challenges roil the industry. As BOEM held its Atlantic Shores review meetings, New Jersey legislators considered a bill to let Ørsted, developer of the neighboring Ocean Wind 1 project, to keep federal tax credits instead of passing them on to utility customers – a sweetener for mounting costs.

“We have a tremendous amount of engagement with all the developers and have a very good understanding of the risk they are taking in terms of their investment,” said Baker. “This is still very much a fledgling industry, and our role is really to put as much certainty in terms of transparency, accountability into our processes, so that we can give the industry confidence in how we’re making decisions.”