Offshore wind energy got its prime-time national spot when former president Donald Trump promised to shut down all U.S. projects if he wins the White House again.

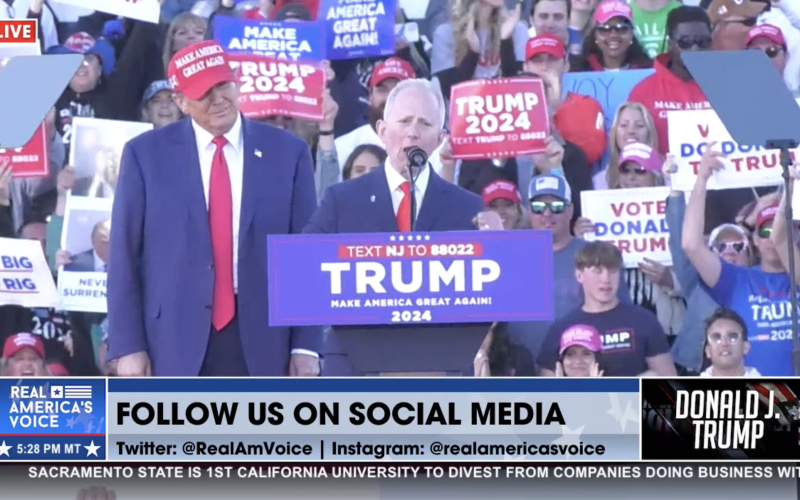

“We are going to make sure that ends on day one, I’m going to write it out as an executive order,” Trump told the crowd at a May 11 beachfront rally in Wildwood, N.J.

In the days following, other Republican politicians hastened to enhance their anti-renewable energy credentials. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed a law to prevent offshore wind development in state waters, repeal requirements for considering climate change in energy policies, and end state renewable energy and conservation programs.

The new law effective July 1 “will keep windmills off our beaches, gas in our tanks, and China out of our states,” DeSantis wrote on social media. “We’re restoring sanity in our approach to energy and rejecting the agenda of the radical green zealots.”

DeSantis signed the law two weeks before the start of what veteran hurricane watchers at Weather Bell Analytics predicted as early as Dec. 7 to be “a hurricane season from hell” owing to a confluence of factors.

Record-setting sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic basin and Gulf of Mexico preceded a shift from El Nino to La Nina conditions in the Pacific, optimizing prospects for the highest number of tropical storms in years, according to the National Hurricane Center, Colorado State University and other research centers.

To critics it looks like DeSantis and his allies in the Florida legislature have hung a “kick me” sign on their own backs. Southwest Florida still struggles with the long-term impacts from Hurricane Ian’s category 4 landfall in 2022.

Insurance companies, looking at increased hurricane risks, are boosting homeowners’ annual premiums. Florida’s political establishment appears unable to do much about it, and that’s threatening the state’s real estate market – the engine that drives Florida’s economic success.

But no worries about the sight of future wind turbines driving down those home prices! In fact, offshore wind developers and the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management have shown no real interest in developing wind energy areas off Florida. Wind speeds there are just not that attractive. In the western Gulf, there’s more interest off Louisiana and the potential for harnessing offshore wind to power industry and future hydrogen fuel production.

Yet for all the chest-thumping against renewable energy, Floridians have little appetite for seeing oil and natural gas developers off their shores.

In January 2018 then-Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke abruptly announced the Trump administration was taking the eastern Gulf of Mexico out of consideration for new offshore oil and gas leasing. Critics saw it as a political move to benefit then-Florida Gov. Rick Scott, who would shortly undertake his campaign for the U.S. Senate.

That came as a surprise to offshore energy advocates, who eagerly anticipated Trump’s promise to open more offshore leasing. As the 2020 presidential campaign tightened in September that year, the offshore industry felt ambushed again, when Trump announced he was extending a 2012 Obama-era drilling moratorium off the Southeast coast.

That turnaround came as the Trump campaign and Republicans saw poll numbers improving for challenger Joe Biden. Opposition to offshore oil development had long been a bipartisan issue in Florida, and Trump’s move toward extending the moratorium off South Carolina aimed for more voters’ support in the tourism-heavy Lowcountry region.

In Campaign 2024, the lineup for and against offshore wind comes as no real surprise. The Biden administration’s juggernaut of proposed wind power development continues apace, and the ferocious opposition of East Coast beach resort communities and the fishing industry is a ready pool of votes for a second Trump administration.

.JPG.small.400x400.jpg)