While preparing for a short write-up of a new ferry under construction in Vancouver, British Columbia, for February’s On the Ways section of WorkBoat, I discovered a hornet’s nest of opposition to the project.

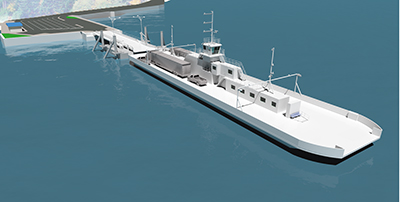

The primary issue is the design and propulsion: it’s a cable ferry. Instead of diesel engines turning propellers and steering with rudders, the boat’s engines will be turning a bull wheel wrapped with a cable attached to the beach at each end of the route. Two other cables, one on each side, will guide the ferry as it crosses a 1,900-meter passage between Vancouver and Denman islands. No propellers, no rudders.

The residents of Denman Island (and Hornby Island, which is only accessible by another ferry on the other side of Denman) are freaked out. A press release put out by the opposition is titled: “Has the BC Ferry Corporation gone insane?” In the release, Dr. Colin Boyd, “a renowned expert of transportation accidents,” says, “The residents of Denman and Hornby islands feel like they are helpless lab rats in some kind of mad scientific experiment being forced on them by BC Ferries. They are protesting again at the Denman Ferry Dock, but despair about how on earth they can stop this madness.”

Apparently, they can’t. The ferry is under construction at Vancouver Shipyards and is scheduled to enter service next summer.

For its part, BC Ferries is confident that the cable ferry will perform satisfactorily, having had extensive engineering studies and reviews by outside firms, including a safety study by Lloyd’s. BC Ferries is also touting the project as environmentally beneficial in that it will require much less fuel to operate. In fact, the ferry service expects to save about $2 million a year in operational costs, compared to the conventionally powered ferry being replaced.

A large part of those savings, however, will come from reduced manning, from six to three, in addition to lower fuel bills. The reduction in manning also frightens residents concerned about safety. And it’s a social and economic issue in that many of the current BC Ferries employees live on Denman Island.

Peter Kimmerly, a former BC Ferry and icebreaker captain and now a resident of Hornby Island, has also publicly opposed the cable ferry, but he said he could support it if it had thicker cables and a deeper, heavier hull.

Mark Wilson, vice president of engineering for BC Ferries, says that his corporation has been doing feasibility studies and engineering analyses for years and that the new cable ferry will deliver “the same level of safe, reliable and efficient service” as the ferry being replaced.

Cable ferries are nothing new. There have been hundreds of them around the world for decades. Some have used chains instead of cables. Pulling a vessel along a cable or chain is like an elevator going horizontally, according to John Waterhouse, chief concept engineer at Elliott Bay Design Group, one of the firms that has worked on the cable ferry project. “It’s a reliable mechanism, there’s not a lot to break down, and it’s a lot more efficient that turning propellers.”