Some Jersey Shore people who recovered and rebuilt their homes after Hurricane Sandy say projects like Atlantic Shores Offshore Wind must be part of the renewable-energy answer to climate change and rising sea levels. The storm legacy loomed large in this week’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management scoping sessions.

The New Jersey shoreline “is in critical danger of being destroyed by climate change,” said marine science teacher Amy Williams of the New Jersey Organizing Project, a community group that arose after Sandy struck in October 2012.

For others, the prospect of 800-foot turbine towers on the horizon 10 miles off Long Beach Island presages another kind of disaster.

The location is “completely inappropriate” said Wendy Kouba of the LBI Coalition for Wind Without Impact, a group calling for BOEM to include its Hudson South wind energy area – 30 to 57 miles offshore ¬– as an alternate site in the environmental impact study for Atlantic Shores.

With two major offshore wind projects – the Atlantic Shores joint venture by Shell New Energies US LLC and EDF Renewables North America, and Ørsted’s Ocean Wind on a neighboring lease to the south off Atlantic City – New Jersey has become a battleground for the wind industry’s fiercest critics and supporters.

Commercial fishing conflicts are one major issue for the New Jersey projects. Barnegat Light and Cape May are ports for the thriving sea scallop fishery, while large volumes of surf clams are landed in Atlantic City and Point Pleasant Beach.

Both fleets have engaged with BOEM and wind developers for years, foreseeing their dredge boats could be effectively excluded from future turbine arrays with their towers and buried power cables.

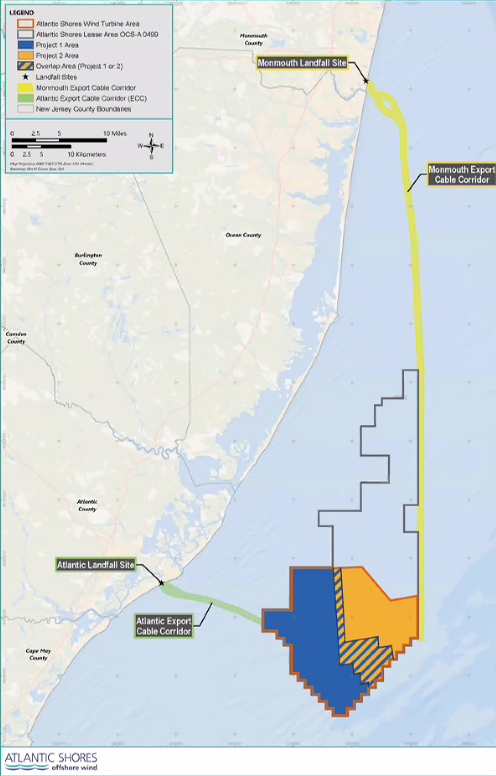

The first phase of Atlantic Shores is planned as 200 turbines, in a grid pattern of 1.0 by 0.6 nautical miles, said Jennifer Daniels, development director for Atlantic Shores. That design was laid out to align with most fishing vessel traffic through the area, she said.

But scallop and clam fishermen still complain that few of their concerns bring changes. “We make suggestions and get no response except ‘Thank you for your comments,’” said David Wallace, an advocate for the clam industry.

With proposed turbine arrays that put tower locations in 1-nautical mile grids, it will not be safe for clam vessels towing their heavy hydraulic dredges to continue fishing those areas, said Wallace.

The clammers have insisted they need 2-nautical mile spacing for safety. Without changing those plans, lease areas off the beaches will be lost to fishing and wind developers should provide mitigation and compensation for the fishing industry, as wind projects will be more efficient with larger turbines, said Wallace.

“They can get more money by putting these bigger turbines into a smaller space,” he said.

Charter fishing captain Paul Eidman of Anglers for Offshore Wind Power cites how Ørsted’s Block Island Wind Farm – the five-turbine pilot project built in 2016 – has become a fishing destination in its own right, attracting fish, recreational anglers and charter boats to its tower foundations.

Eidman said recreational fishermen can live with wind development if three principles are respected: Unrestricted access to turbine foundations, serious input and advice accepted on siting and planning, and scientific studies of the changes before, during and after construction, with all data transparent and available to the public.

Fishermen are on the front line of climate change right now, with fish species like surf clams and black sea bass already clearly shifting their stock ranges northward, well documented by fisheries scientists and management agencies.

“Whether they admit it or not, every fisherman out there sees the effects of climate change,” said Eidman.

But for the New Jersey critics, the 30-megawatt Block Island project is a blip compared to the scale planned for Atlantic Shores. The 1,510 MW project, 10 to 20 miles offshore, would extend from off Atlantic City to Long Beach Island.

“Block Island is not even a comparison to what’s proposed off Long Beach Island,” said Kouba.

Her LBI group, including island businesses and homeowners, predicts there could be more than $300 million in losses to the island region’s economy, and is preparing a legal challenge to the plan.

Wind advocates insist those claims pale compared to climate threats.

“It is a clear energy gold mine but we have to be able to tap it,” said Doug O’Malley of the Environment New Jersey group. The Jersey Shore “is the most vulnerable coastal community right now” with two feet of sea level rise predicted in this century, he said.

Part of the conflict lies in the history of BOEM’s early years planning offshore wind.

In 2009 the new Obama administration was embracing offshore wind power, and then-Interior Secretary Ken Salazar came to Atlantic City for a press conference to talk about developing the industry off the East Coast. BOEM was just starting to map out where the so-called wind farms could go – and learning how the New York Bight has some of the most crowded waters on the East Coast.

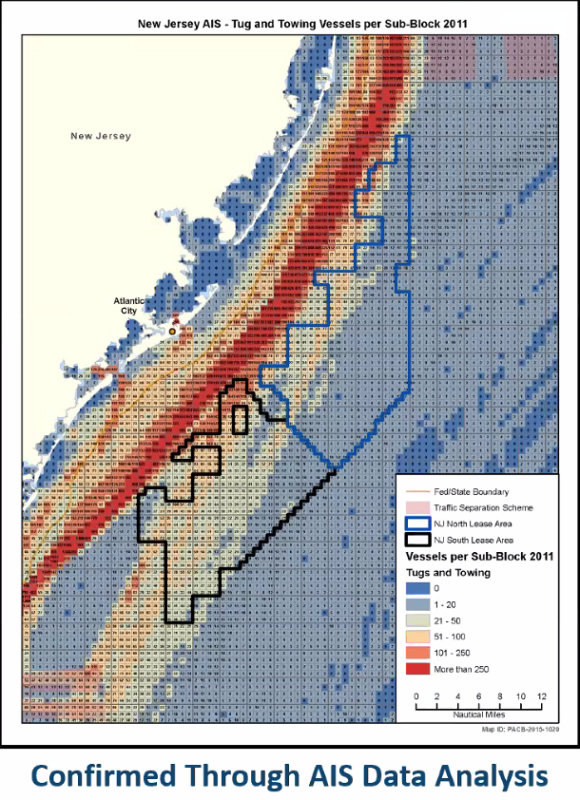

With three traffic separation lanes radiating from New York Harbor like spokes, there was the obvious constraint of big ships. Planners soon learned from mariners and AIS data of the less-charted but busy nearshore routes transited every day by everything from barge tows to fishing vessels.

Despite years of consultations, there are still changes needed to ensure safety of shipping, said Edward Kelly, executive director, of the Maritime Association of the Port of New York and New Jersey. “We believe there is enough space in the New York Bight to coexist with other user groups,” said Kelly.

But the maritime community is “still distressed” by a persistence of 1-nautical mile setback for turbine arrays from some shipping lanes, he said.

Wind development “must be looked at on a cumulative basis, with full build-out throughout the New York Bight,” Kelly stressed. “Even a small marine casualty…would be devastating to the New Jersey economy.”

Visual impacts from shore were one thing that was not so much on the radar back then in 2009 to 2011, said BOEM specialist Will Waskes.

New York State energy planners faced that conflict with coastal resorts on Long Island, the preferred summer getaway for moneyed New York City residents, and decided to retreat from the visual-impact fight. The state’s policy has been to prefer wind sites at least 17 miles offshore, and urged BOEM to set that limit on future lease plans.

Those complaints about visual impacts give pause to some inland New Jersey residents, who saw immense tax dollars spent on post-Sandy beach replenishment.

Seaside homeowners and beach businesses objecting to wind power development “will be the ones who want to government to pay” for escalating damage from storms and sea level rise, said Paul Teshima of Morristown.

Other commenters said offshore wind energy can help convert New Jersey’s energy supply to renewable sources, but must be done in balance with the region’s longstanding economic, social and cultural character.

For fishermen and coastal communities affected by wind power development, “these people should be made whole. We shouldn’t forget that,” said Jamie Klenetsky Fay, an inland Morris County resident with roots and family in seaside Monmouth County, close to the proposed New York Bight wind energy areas.

But without developing new renewable energy sources to deal with climate change, she added, “so many more will be hurt if we do nothing.”