A study by students at the Brown University Climate and Development Lab charts relationships among groups opposed to offshore wind energy projects off the U.S. East Coast, and calculates that conservative and libertarian groups with ties to legacy fossil fuel have channeled $72 million into the opposition movement since 2017.

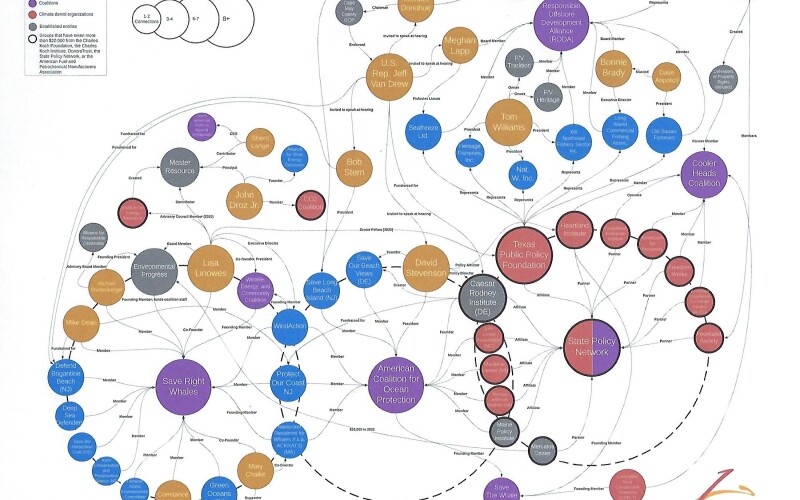

A centerpiece of the report is a graphic diagram of those relationships, and funding shared among some groups that are players in furious public debates over wind projects.

“This map illustrates the deeply interwoven relationships between new grassroots- appearing anti-offshore wind (anti-OSW) groups and known fossil fuel-allied actors in the conservative movement,” the Brown researchers wrote in an introduction. “Though journalists have illustrated specific connections between local actors and national interests, no cohesive understanding of offshore wind opposition exists.”

They say the “report reveals how these East Coast offshore wind opponents are not solely local – they are embedded in a network of seasoned fossil fuel interests and climate denial think tanks that have perfected obstruction tactics for decades.”

“These new grassroots-appearing groups and experienced obstructionist think tanks share legal support, public speakers, leadership, and information and tactical subsidies,” wrote authors Isaac Slevin, William Kattrup and professor J. Timmons Roberts. “Though they appear to operate organically, in many cases they are directly supported by well-funded, national organizations with ties to the fossil fuel industry and dark money. This creates a facade of local opposition that is actually part of a broader, sustained anti-renewable energy campaign.”

“We think this is going to be useful” for researchers and journalists, said Roberts, who is a professor of environmental studies and sociology at Brown University and executive director of the university’s Climate Social Science Network.

It’s not the first close look from Brown University researchers about offshore wind opponents. An April 2023 paper from the Climate and Development Lab contended Rhode Island activists used misleading arguments to influence public perceptions of wind projects proposed off southern New England. That project got them looking into broader, national connections among opposition group, said Roberts.

“With increasing frequency and coordination, national-level fossil fuel interests have involved themselves with grassroots-appearing groups in a half dozen states along the Eastern Seaboard,” the authors wrote. “Local groups such as Protect Our Coast NJ and Save Long Beach Island have entered partnerships with think tanks that receive money from the fossil fuel industry and its allies, and that have been identified in the literature as climate denialists.”

That has angered some activists, like the Save Long Beach Island group, who posted on social media a claim that Brown researchers were “spreading lies” about anti-wind power protesters being funded by fossil fuel interests.

While the study notes connections among groups, it does not say Save Long Beach Island gets funding, said Roberts.

“We don’t want to make any claims we can’t support,” he said.

In the upper right corner of the report’s graphic is a constellation of commercial fishing groups, who were raising concerns about environmental effects of building wind turbines long before seaside property owners. Central among the fishing groups is the Responsible Offshore Development Alliance, which organized in spring 2018 with scallop fishermen and other East Coast operators as its first members.

The Brown authors note that six fishing businesses that are members of RODA are also represented in a lawsuit by the conservative Texas Public Policy Foundation challenging permits for the Vineyard Wind project, now under construction off southern New England. Like Save Long Beach Island, RODA is shown in the report for its ties to various groups, but not for any direct funding.

RODA executive director Annie Hawkins said the fishermen have steered an independent course, and have worked with government agencies and university scientists studying how offshore wind development may affect the industry and ocean environment.

“We are a non-partisan trade association, and while we do have board members working on a lawsuit with the Texas Public Policy Foundation, we also have others with much different backgrounds and our association doesn't work directly with (nor accept funding from) the other groups mentioned in the report,” Hawkins told WorkBoat. “We also have significant partnerships and collaborative work with all types of entities including federal and state agencies, research institutions, and others that amount to a much more complex narrative than the report implies.”

Hawkins said “100% of RODA's advocacy funding comes from within the fishing industry (and) 100% of our research program funding comes from scientific grant entities including NMFS, state agencies, and the like. We also occasionally receive small facilitation contracts for topics that are prioritized by our members and approved by our Board. This is all clearly shown in our tax filings, which as a non-profit are fully public.”

The Brown University team plumbed such tax filings to profile the role of other actors too. In charting relationships among wind project opponents, the Brown researchers list “18 local groups and businesses, 14 climate denial think tanks, 8 coalitions, 11 other established entities, and 16 key individuals.”

“Though donor-advised funds and disclosure issues make it impossible to reveal all direct funding sources, we identify a direction of influence extending from dark money donors and fossil fuel organizations to local grassroots-appearing groups,” the report says. “We identified six major fossil fuel and dark money donors – the Charles Koch Foundation, the Charles Koch Institute, DonorsTrust, the State Policy Network, and the American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers Association – that fund 17 think tanks involved in the anti-OSW network.”

“The think tanks, in turn, influence local anti-OSW groups by providing financial resources, legal support, and personnel. We identify a total of $72,276,593 in contributions from the six major donors to groups in the network between 2017 and 2021.”

On the receiving end of the money, the Texas Public Policy Foundation is one of the largest recipients, taking more than $6.6 million from the Charles Koch Foundation and Charles Koch Institute between 2017 and 2021, according to the Brown study.

An important regional player is the American Coalition for Ocean Protection, or ACOP, organized in summer 2021 in opposition to southern New England wind projects, according to the researchers. Its founding president David Stevenson is a former member of the Trump administration’s Environmental Protection Agency and policy director for the Caesar Rodney Institute, a Delaware-based libertarian think tank that has also been allied with southern New Jersey wind power opponents.

“ACOP is an ambitious project. It joins five libertarian think tanks in five different states with five organizations fighting against specific offshore wind initiatives on the local level,” the report says.

“It’s important to follow the money. But that’s only part of the story,” said Isaac Slevin, a Brown student and member of the research group. “There are a lot of links, some financial, some not.”

Th most difficult work for the group was verifying the complex links and the financial connections, he said: “We really wanted to make sure we were right on this.”

One striking aspect of the anti-OSW network is the sharing of tactics and rhetoric, both in mainstream media and on social networks, said Slevin.

“The flow of dollars from right-wing megadonors and think tanks is critical to the activities of the anti-OSW movement, but money only tells one part of the story. Without financial strings attached, individuals and organizations with widely varying missions and degrees of national influence have engaged in complex trades of information and tactics that have helped advance the movement,” the report notes. “When a leader of one offshore wind group speaks at another’s event, or when an article published by a prominent national think tank appears in an anti- OSW Facebook group, talking points and strategies spread across the movement.”