Plans to open more of the New York Bight to offshore wind development will threaten the East Coast scallop fishing industry that brings in more than $425 million in dockside value annually and much more to the larger U.S. economy, fishing advocates say.

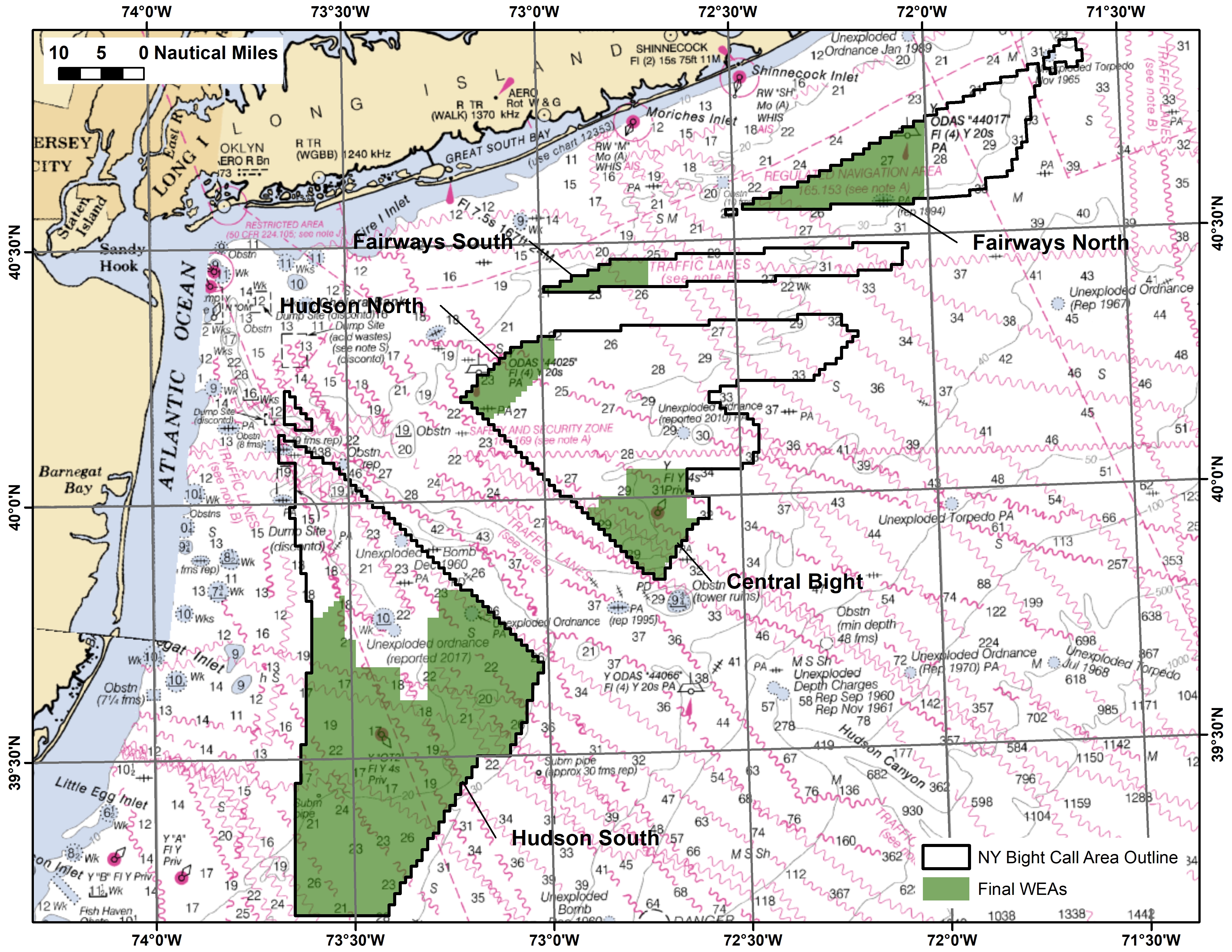

They say one immediate step should be creating a 5-nautical mile buffer zone between the southeastern edge of the Hudson South Lease Area that’s been proposed by the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, and the Hudson Canyon Access Area, highly productive scallop grounds that have supported the industry’s immense success over the last 20 years.

In the late 1990s, fishing pressure, declining scallop numbers and fishermen catching smaller scallops brought the fishery to crisis. But fishermen, scientists and regulators regrouped, creating a system of rotational scallop area management that federal scientists say has added more than $1 billion in revenue to coastal communities.

The drive by the Biden administration to develop more offshore wind, avidly supported by state governments in New York and New Jersey, will threaten that progress, representatives of the Fisheries Survival Fund and the port of New Bedford, Mass., told BOEM officials in a July 20 online conference, the group said.

“Proposed lease areas need to be thoroughly re-evaluated to reduce impacts to scallops and scallop fishermen, who operate in the most valuable federally managed fishery,” according to a statement issued by the group this week.

Beyond operational difficulties of fishing around wind installations, the technology “presents many potential environmental threats to marine ecosystems,” the Fisheries Survival Fund says in a summary:

- Assembling turbines and foundations “displaces large amounts of sediment on the seafloor, creating scour and sediment plumes that can interfere with scallop growth and filter-feeding processes.”

- “The turbine arrays themselves can disrupt ocean currents and thus scallop larval flow and settlement.”

- “Wind farms create habitats for other filter feeding species like mussels, which compete for available phytoplankton, change the biological makeup of the surrounding area, and interfere with the sustainability of the resource.”

- “Young scallops also face increased predation from marine life known to proliferate in wind energy installations such as starfish and moon snails.”

- “Seismic activity involved in wind farm site assessment activities has also been shown to damage scallops.”

The proposed buffer zone would create a 5-nautical mile strip inside BOEM’s mapped Hudson South wind energy area, standing off any future turbine construction from the southeastern edge that borders the Hudson Canyon scallop access area, said David Frulla, a lawyer with the Washington D.C. firm Kelley Drye & Warren who has represented the fund and other fishing groups.

“The buffer zone’s purpose is to make sure there is not a wind farm hard up against an access area,” said Frulla.

Scallops were worth well over $500 million to coastal economies in 2019 and nearly $750 million “when taking into account their processed value. And this does not include the additional economic value added by the remainder of the supply chain until the product ultimately reaches consumers in markets and restaurants,” according to the Fisheries Survival Fund.

Founded in 1998, the Fisheries Survival Fund was an industry reaction to its crisis then, and now includes fishermen Maine to North Carolina. The group says it continues to work “with academic institutions and independent scientific experts to foster cooperative research and to help sustain this fully rebuilt fishery.”

Scallops are a colossal part of New Bedford’s economy, bringing in $265 million in 2019 or 80 percent of the fishing industry’s dockside value there in 2019, according to the New England Fishery Management Council. It far outpaces Dutch Harbor, Alaska in value even with 114 million pounds in landings versus 763 million pounds at Dutch Harbor, according to NMFS annual reporting for 2019.

With their high per-pound values scallops have an outsized value for ports large and small.

Right behind New Bedford in 2019 was Cape May, N.J., with almost $54 million or 81 percent of its dockside value. Sixty miles north on Long Beach Island, scallops brought in $19.4 million that year, 77 percent of the sales.

“Damage to the scallop industry will have far reaching consequences for working families in ports throughout the Atlantic coast,” according to the Fisheries Survival Fund. “The harm will extend beyond fishermen and processing plant employees – many of whom are recent immigrants – to fuel docks, marine equipment suppliers, restaurants, and markets.”

BOEM organized the July 20 meeting to hear from scallop, trawl and surf clam fishermen, and the agency plans another Aug. 6, said Frulla.

Last week representatives for scallopers and the port of New Bedford made their case that BOEM “has been more responsive to concerns of wind developers and other ocean user groups like the military and commercial shipping interests than to those of fishermen.”

The agency needs to hold in-person meetings with fishermen because many are not accustomed or equipped to participate on Zoom and similar online platforms, the group says.

While offshore wind development may bring new jobs and economic development to coastal communities, “the benefits should not come at the expense of those who have historically relied on the scallop fishery to provide for their families,” the group says.