The U.S. barge industry, which largely supported Donald Trump for president, has found itself in an uncomfortable position of late with the president’s promise to spend $1 trillion to shore up the nation’s sagging infrastructure.

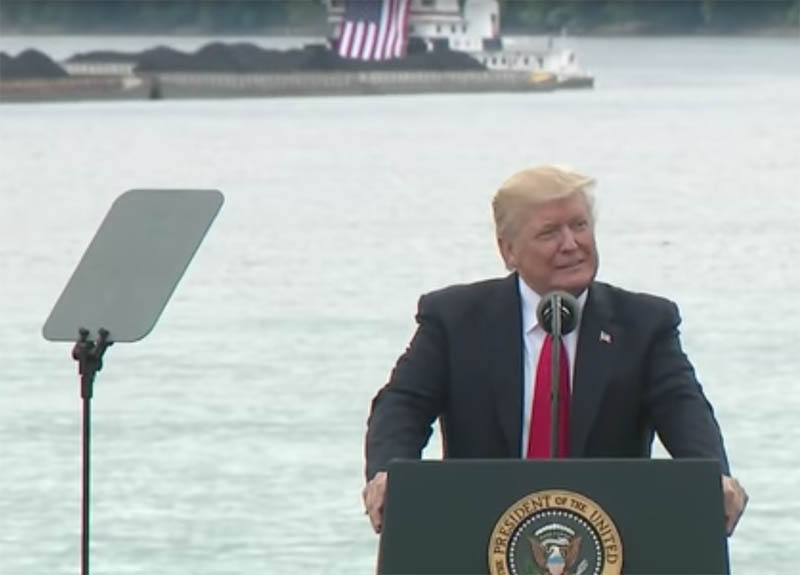

In principle, the inland industry should be elated. They finally have a president who has put a spotlight on the needs of the nation’s aging and failing inland navigation system. In Cincinnati last week, with an Ingram barge loaded with coal as a backdrop, President Trump laid out for a national audience the urgent needs of the waterways system.

He called rivers “critical corridors of commerce [that] depend on a dilapidated system of locks and dams that is more than half a century old and their condition is in very, very bad shape.” He also quoted figures often used by the industry that show how waterways economically and safely move tons of goods for domestic and export markets.

Groups that represent the barge and agricultural industries praised the president for his attention to the industry. Mike Toohey, president and CEO of the Waterways Council Inc. (WCI), which advocates for waterways infrastructure funding, said it was the first time in his career that he’s seen a president show such a high profile interest in river navigation. Rails, bridges and highways always get the nod, while rivers seem to be an afterthought, if they get any thought at all.

So far, the president has revealed little about how he will organize and fund his $1 trillion infrastructure plan and how it will affect the waterways. But what his administration has offered up so far is troubling to the barge industry, and is laden with policy contradictions. As a result, the industry has found itself in the position of trying to stop actions that might harm their operations, as much as promoting policies for a new infrastructure plan that would help navigation.

Consider this:

- The Trump administration wants to invest more in modernizing inland infrastructure and reducing the red tape and permitting that bogs down many civil works projects, but has proposed a 16% cut in the budget of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which builds and maintains the inland waterways system.

- The president’s fiscal 2018 budget includes funds for only one inland modernization project: the much-delayed Olmsted lock and dam on the Ohio River.

- The budget offered up what WCI calls a “recycled” user fee concept for commercial users of the inland waterways as a revenue-raiser for waterways improvements. The industry has vigorously opposed such a fee in the past, saying it already pays into a fund for inland projects through a diesel tax. It also says additional fees are unfair as barges aren’t the only users of the rivers, and would essentially double what the industry is now paying into the Inland Waterways Trust Fund, a public-private partnership that funds inland projects.

- By doubling what operators are paying, but only spending on Olmsted, the budget proposes to spend only a small fraction — about 12% — of total revenues coming into the trust fund on waterways. WCI asks why barge operators should pay double if the government intends to spend so little and use the revenue for other government programs.

- Trump has said that infrastructure improvements can be better financed by public-private partnerships that involve more private capital investment in place of tax dollars. But this doesn’t work well in river transportation, where there are multiple users of the rivers, the industry says. Operators further argue that they already have a successful partnership at work through the IWTF, which shares the cost of new projects 50-50 between Uncle Sam and the industry through the diesel fuel tax. So far, the administration has offered no details on how this might work for waterways.

The new attention lavished on river navigation is certainly welcomed after all the years that waterways operators have toiled in the shadows of the U.S. transportation system. But the devil is in the details, and the industry has its work cut out for itself itself to make sure that an infrastructure plan intended to improve the waterways doesn’t change things for the worse.