Newly developed propulsion options are making a difference in the Arctic to San Francisco Bay.

At the Electric & Hybrid Marine Expo North America Conference and Exhibition held in Houston this week, stakeholders from across the maritime sector explored what these details look like in the present while also predicting how they’ll affect the future for owners and operators.

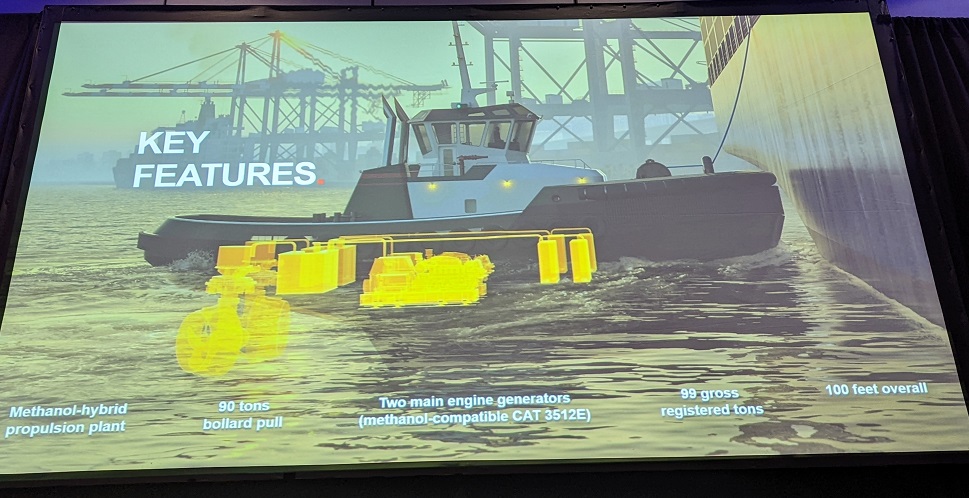

In the "Futureproofing your Fleet: A Low-Carbon Tug Designed for the U.S. Market" session, Dave Lee from ABB and Peter Soles from Glosten took to the stage to detail the SA-100, a dual-fuel hybrid electric tug design that would enable operators to keep costs down.

Those details were key to the development of the tug, as Glosten began to field questions in 2019 and 2020 around the creation of a fully electric tug. Soles said that at the time there was no demand for it. Expensive to build and operate, and the regulatory and operating risks prevented the company from moving forward with the development of this type of vessel. Doing something all-electric felt out of touch.

Fast forward to 2022, and Soles explained that his opinion began to change. He saw a growing interest in commercially viable and hybrid designs but an unwillingness for operators to get priced out when adopting them.

“It’s okay to make incremental advances but there are still operational and logistical boxes that need to be checked,” Soles said.

Eventually, a concept for a competitive tug came together. Three factors were key considerations. Their design needed to deal with regulatory uncertainty, define an environmental impact, and address business practicalities. That led to the joint development of the SA-100.

The methanol-hybrid propulsion plant, 90 tons bollard pull, and two main engine generators, 99 GRT, define the main features of the vessel.

While the challenges with methanol are well known, Soles explained the decision around using methanol came down to the practicality as the most viable and “future-proof” diesel replacement option.

Lee detailed how similar questions and conversations had been taking place internally at ABB and with their customers, some of which focused on why they hadn’t gone all-electric. The answer then and now comes down to where and how the tug will operate.

Electric passenger vessels can make sense because you always know where they’re going to be but that isn’t the case with tugs. All electric tugs have their place, but that’s within a 2.6 nautical mile route, rather than one that stretches 10.5 nautical miles.

Both Lee and Soles mentioned how these specifics factored into component decisions with the SA-100, which included why they wanted to utilize the Caterpillar 3500 series engines.

Ultimately, the total cost of ownership comes down to considerations around the best balance of capability, versatility, and cost/complexity. The balance considers how these new engines can be smaller when compared to traditional tugs of this size and how these new builds may qualify for a variety of federal and state grant funding programs.

“There is no guarantee that a mechanical diesel tug built today will be less costly,” Lee said.

Joshua Sebastian of the Shearer Group further detailed how electric towboats are viable from a commercial perspective. His background as an engineer defines an approach that is focused on the people who are actually doing the work, meaning the technology has to be able to function and deliver as intended.

Joshua Sebastian of the Shearer Group further detailed how electric towboats are viable from a commercial perspective. His background as an engineer defines an approach that is focused on the people who are actually doing the work, meaning the technology has to be able to function and deliver as intended.

That capability was something he highlighted with the Zeeboat, which is designed to decarbonize short-sea shipping. While there are major goals associated with decarbonizing deep-sea shipping, short-sea shipping is different. Electrification of tugs like the Zeeboat is being positioned as the answer to short-sea shipping challenges by being more than a barge.

This short video describes the need for these sorts of solutions in short-sea shipping and the value that Zeeboat specifically enables:

While the product opens up the path towards decarbonization of the entire sector, the short-term practicality from the perspective of vessel owners and operators is something Sebastian made sure to highlight.

“Our numbers show how adoption can make your OpEx go from $100 million to $10 million,” Sebastian explained. “While the environmental impact is there, it’s also a commercially viable option that is based on traditional inland towboat construction costs, scalability, volumetric efficiency.”

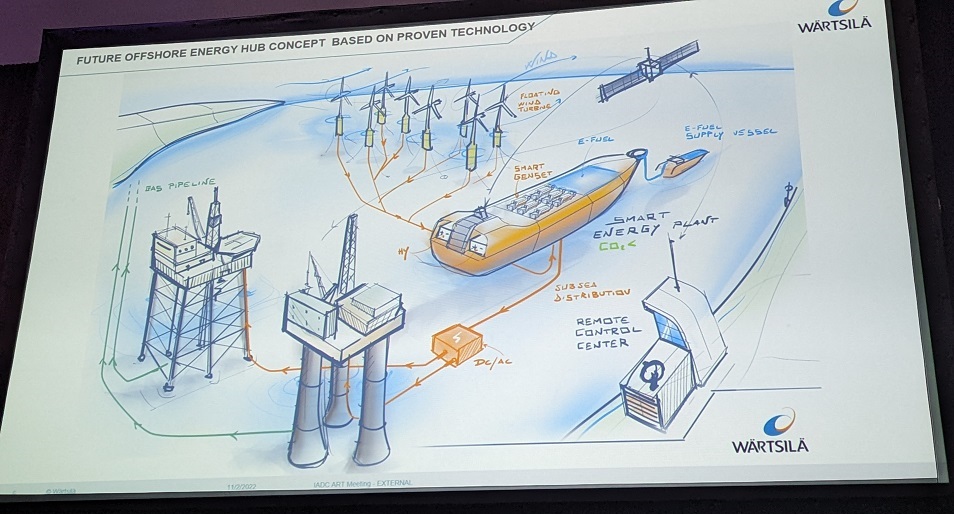

Later on, Joel Thigpen from Wärtsilä detailed the many viable pathways to decarbonization through electrification, hybridization, and fuel strategies. He spoke about what it means to design a vessel that will be ready for the potential technologies and challenges of the future while designing a particularized and optimized solution today. That exploration included a look at Wartsila’s concept for a future offshore energy hub.

Regardless of what these changes actually look like or what it will take to enact them, all of them need to consider options that utilize everything from yellow hydrogen to direct air capture (DAC) processes. Wartsila actually has a dictionary that details many of these terms and processes.

Ultimately, there’s not a single answer for what’s next for the maritime sector or for owners looking to make a decision on what system of propulsion will be used for their individual fleets.

“There are options now,” Thigpen said about how diesel alternatives are affecting vessel design. “It really comes down to the question of ‘What’s it going to take?’”