A national, pandemic-infused labor shortage has made an already tough hiring environment in the maritime industry even worse, sending inland barge companies into recruiting overdrive and setting off alarms about whether the industry will have enough workers now and in the future as demand for barging rebounds.

Faced with a generation of older workers retiring, a new generation that knows little about maritime careers, and coming off an infusion of federal aid during the pandemic that kept people at home while drawing benefits, barge companies are having to be creative and proactive to fill vacancies.

They are increasing their presence at job fairs and on social media (posting on TikTok is a current favorite), venturing far beyond their local areas to drum up interest in waterways careers, hiring professional recruiters, increasing pay, expanding training, and making pitches to a more diverse applicant pool.

INCREASED LABOR COSTS

On top of the challenges in finding people is the high cost of paying new recruits and existing workers. Operators say they are being hit with high labor costs at a time when barging is just starting to make a comeback and company profits are fragile. Some barge companies have had to turn down work because they are short-staffed.

And there’s general agreement among operators and others who track the industry that the situation isn’t likely to get better anytime soon.

Labor challenges were on everyone’s mind at a meeting of the American Waterways Operators in May, according to AWO CEO and President Jennifer Carpenter. With labor shortages across all sectors nationally, barge companies must compete with other industries that offer good salaries, signing bonuses, and no time away from home.

Barging “is an essential sector with strong implications for national security, so we need to make sure we have a pipeline of people who want to come into this industry and make a career of it,” Carpenter said in an interview. “The short-term challenge (for operators) is making sure we’ve got people to run the boats now and we have the people to grow the industry into the future. Those are big issues for our members.”

There is no immediate playbook or solution to this, and companies must take a many-sided approach to recruiting and employee retention, Carpenter said.

“A number of folks thought that it would have righted itself sooner,” she added. “If there was an easy solution, folks would have found it. If there was one lever to be pulled, they would have done it. Instead, everyone is facing the reality that it’s going to be a multifaceted effort and there are things we need to do to tell the story of the industry and companies are going to have to put resources into recruitment.”

The increasing cost of labor is a big concern for operators. “It has gotten to the point of people (in the industry) looking at automation and different things that I never thought we’d be embracing, but the cost of people is pushing the unsustainable limit,” said Austin Golding, president and CEO of Golding Barge Line, Vicksburg, Miss., a tank-barge operator that moves refined petroleum and chemical products. “In our industry, it’s gotten there from a lot of consolidation, which means less focus on long-term things like training people.”

He said companies leaving the barging business didn’t invest in training because they had an exit plan in place. “We weren’t making enough money to pay for the training that we’ve traditionally done on our boats. During the downturn in the industry, part of the cost-cutting measures were training and part of the cost-cutting is coming back to bite us, as there are not as many people who have been trained and the demand is up and we’re short of people.”

CREATIVE HIRING PRACTICES

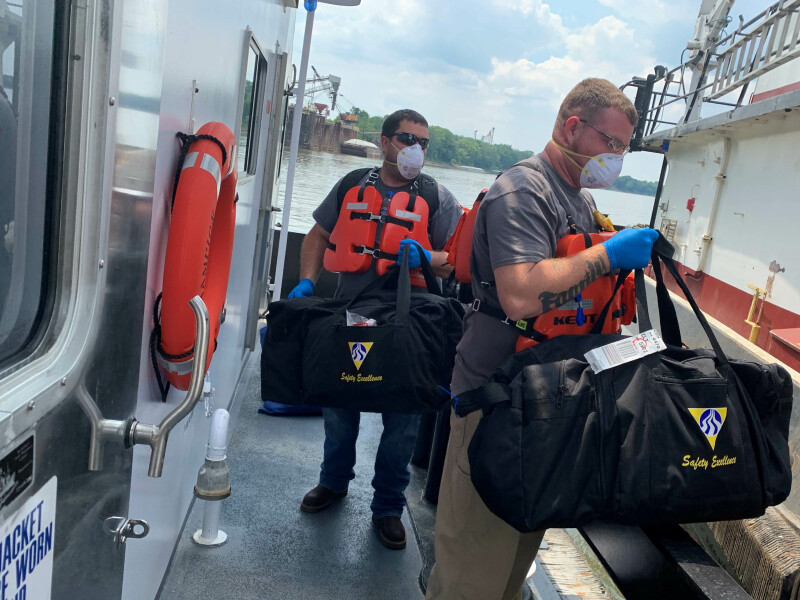

The labor shortage has forced operators to take a hard look at how they operate, from retooling hiring initiatives and reviewing salaries to the comfort of their vessels. One approach is to beef up training programs that offer new hires broader opportunities for well-paid, long-term career advancement rather than emphasizing a job with a good paycheck.

Campbell Transportation Co. Inc. (CTC), a Houston, Pa.-based barge line that moves coal and liquid products along the inland system and the Gulf of Mexico, has invested in its in-house steersman training program that will put deckhands through a long training process so they can get their license.

“From day one, when an employee starts, there’s now more frequent opportunities to move up and enhance their training,” Kyle Buese, Campbell’s president, told WorkBoat. “We take care of the training. People don’t want to get stale in their careers or feel like they are getting stale. More frequent career development plans are needed. Those things have worked for us.

He added that today’s new vessels offer much more comfortable accommodations and living spaces, good communications technology, and a much better onboard experience. “The vessels themselves and the comforts are leaps and bounds from what they were 20 years ago,” Buese said. “They are very comfortable, very crew oriented. A lot of these boats have a nicer kitchen than in a hotel or a house. You’ve got to make them a place where people want to be.”

CTC has also hired a full-time professional recruiter with years of industry experience who is focused on finding the right candidates and properly screening them, Buese said. This has meant beefing up the company’s presence on social media, attending recruiting forums and educating potential recruits about the lifestyle on an inland vessel, which many acknowledge is not for everyone with the physical demands and a work schedule that includes long absences from home.

The industry is also learning that it needs to reach out to a far more diverse pool of potential applicants than it has in the past — notably minorities and women, both of which make up an increasingly larger slice of the U.S. population.

Companies are reaching further from their home base to meet with job seekers, are partnering with maritime training schools, and are talking up the profession to high schoolers and even younger students.

Golding Barge is searching beyond its base in Vicksburg, deep into rural areas of the Southeast to reach potential recruits, emphasizing long-term salary and career opportunities.

“If you sit around and wait for people to come to your door, you’ll be in a bind,” Golding said. “We used to have 20 to 40 in a stack of applications to go through all the time. Now we only have a handful that have been cultivated from a proactive movement. We made it a priority to go find people. We go to civic centers, hotels, conference rooms, and to small towns across the Southeast, setting up our own booths and advertising online and locally at job fairs. We’re moving very off the waterways, the more trees the better. You have to show them and hold their hands. We’re not advertising what they will make the day they take the job, but what they’ll make if they stick with the job for five years.”

Still, the problem of convincing people to take a job that keeps them away from home for long periods still persists. “The work-life balance is the number one thing they cite. It’s never the pay or the strenuous nature of the work. It’s always the work-life balance.”

That, Golding acknowledges, is something that will be hard to change given the unique nature of how the barge business operates.