To help meet the energy demands from a growing population, alternative energy sources must work with the environment, not deplete it of its natural resources.

For the first time last year, renewables surpassed coal and nuclear as top contributors to U.S. electricity generation. Today, renewable energy sources (wind, solar, hydropower, biomass, geothermal) generate just over 20% of U.S. electricity.

Offshore wind has become a focal point in clean energy alternatives. The industry has grown exponentially over the past decade, and campaign promises have fortified offshore wind’s place in U.S. energy production.

The Inflation Reduction Act, signed into law in August, grants $40 billion in direct investment to expedite the development of the U.S. offshore wind supply chain. This allotment includes the construction of US-flagged ship builds, further bolstering domestic production throughout the entire industry.

There are hurdles, though, tied to such expansive growth over such a short period of time. The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) noted that the current supply chain challenges faced by U.S. manufacturers can also prove to be future expansion opportunities.

There’s also the overlap of different maritime sectors, particularly autonomous transfer vessels, and subsea robotics, that can be used as an asset for offshore wind companies. The implementation of these vessels can help to reduce crew costs and mitigate risks at sea.

However, opponents are concerned that we need to further explore the effects that these offshore wind farms will have on ecosystem services.

With so much growth in a short period of time, things are changing daily.

Administration energy goals and programs

The U.S. is only producing 42 megawatts (MW) of energy from offshore wind operations. One gigawatt (GW) of potential energy is currently under construction and about 19 GW is in the permitting phase.

The Biden administration has set an offshore wind production goal of 30 GW by 2030. It will power an estimated 10 million homes, support 75,000 U.S. jobs, reduce energy costs for U.S. citizens and enable private investment throughout the entire supply chain, the Biden admistration said. To put it in perspective, globally, fixed-bottom offshore wind turbines account for 50 GW of energy production.

Floating offshore platforms is a relatively new technology, accounting for only 0.1 GW of global production. The administration plans to position the U.S. as a leader in floating offshore wind platforms by advancing lease areas in deepwater, set to deploy 15 GW of floating offshore wind capacity by 2035.

It is projected that roughly two-thirds of the U.S. offshore wind potential exists over bodies of water too deep for fixed-bottom turbines, demonstrating the need for floating platform technology.

Commercially today, offshore floating wind projects are 50% more costly than fixed-bottom platforms. The Department of Energy's Floating Offshore Wind Energy Shot seeks to reduce the cost of floating offshore wind energy by more than 70%, to $45 per megawatt-hour by 2035 for deep water sites far from shore.

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law funds a new prize competition for floating offshore wind platform technologies. These technologies include modeling tools for project design, port needs, and funding for additional research efforts.

Supply chain constraints

The domestic supply chain for offshore towers, blades, nacelles, and substructures is still relatively new. The DOE identifies the need to accelerate supply chain development to meet the administration’s energy production goals.

Inflation Reduction Act incentives have spurred new plant announcements, and that’s likely to gain steam in 2023. Tax credits are offered for the domestic production and sale of qualifying wind components, for critical mineral production, and for projects that re-equip, expand, and build U.S. manufacturing facilities that build these components. These incentives should bring new manufacturing of clean energy elements back into the U.S.

The federal government has yet to clarify many of the details, though that’s not stopping the private sector from following suit with significant investment. In 2021 alone, investors announced $2.2 billion in supply chain funding. Included in their pledge is a commitment to developing nine manufacturing facilities set to produce wind turbine components.

Despite all these supportive policies and investments, growing demand in 2023 could exacerbate supply chain constraints and interconnection bottlenecks, further boosting prices and extending project timelines.

Last year, several factors led to renewable energy’s delayed growth: increased costs, supply chain delays, inflation, trade policy uncertainty, and higher interest rates.

A recent Deloitte survey of 76 executives representing the U.S. power sector noted, “56% of respondents said that while new incentives for domestic manufacturing of clean energy components will spur production, it could take more than two to three years to ease supply chain constraints.”

Another growing concern is the electric grid’s lack of battery storage capacity to handle growing volumes of variable renewables. The U.S. is low on the world totem pole for manufacturing grid storage components. Its current processes for mining raw materials for lithium-ion batteries (cobalt, nickel, lithium) are almost negligible compared to other countries.

Provided the electric grid does have the storage capacity to handle this new energy generation, maintaining that voltage within the operational limit becomes a critical issue. One study explores the “concerns regarding the integration of wind energy to the electricity grids, including wind energy intermittency, resiliency, and reliability issues.”

Port and vessel infrastructure development are also major undertakings that need to scale production.

Shipbuilding

The significant ramp-up in domestic manufacturing of offshore wind components will stimulate growth in ports, shipyards, and the U.S. workforce. Currently, these three areas are all far too limited to support the needed levels of commercial-scale offshore wind energy deployment.

As these projects grow in scale, so then does the need for larger ships. Norway currently has the world’s largest floating wind project, with a turbine rotor diameter of 160 meters. With advancements in turbine technology, future turbine lengths could increase up to 70% by 2030. Offshore wind vessels need to scale alongside these tech advancements to maintain workability on these platforms.

There is currently a shortage of viable vessels capable of performing the build-out of offshore wind farms. Globally, there are only a few vessels that can install large offshore wind turbines. Of that select few, only one meets Jones Act requirements.

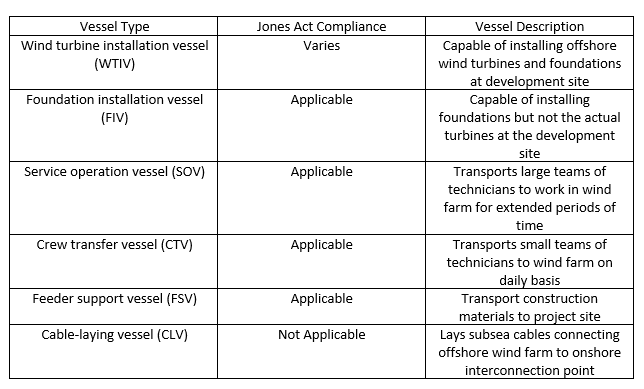

The Labor Energy Partnership broke down the vessels working in offshore wind and their Jones Act status:

“Some of these vessels will need to be developed specifically for the U.S. OSW industry. For instance, any Jones Act–compliant WTIV would need to be newly built for the industry because these types of vessels are uniquely designed for their role of installing the turbines,” and there are currently no operational Jones-Act compliant WTIV’s capable of installation.

The Offshore Marine Service Association and Vineyard Wind (VW) have recently traded blows regarding VW’s use of a Dutch vessel to reposition their anchors.

A recent WorkBoat article further broke down the contractual, regulatory, and legal challenges that shipbuilders and shipowners face when navigating the offshore wind industry.

The Federal Ship Financing Program (Title XI) is a debt guaranteee program intended to promote the growth and modernization of U.S. shipyards. The program encourages U.S. shipowners to obtain new vessels from U.S. shipyards in a cost-effective manner, as well as modernizing their facilities for building and repairs of offshore wind vessels. Studies are now being conducted on developing the optimal fleet size to minimize the transportation costs of offshore wind farms.

Opposition

Off the New Jersey coast, the recent uptick of whale deaths in 2023 have initiated local and federal officials of both parties to seek answers from NOAA and BOEM. NOAA and BOEM said that there is no link between recent whale deaths and offshore wind surveying projects.

Just last month, on the Oregon coast, the Pacific Fishery Management Council voted that the BOEM do a complete reset on its offshore wind farm planning areas. The offshore energy site proposals are to completely start anew to minimize siting impacts to fisheries and ecosystem resources.

The second day of the 2023 International WorkBoat Show will begin with the Offshore Wind Breakfast. Discussions will take a look at what is being developed on the East Coast and the Gulf of Mexico, with a focus on supply chain potential for ports, shipbuilders, and turbine components.

For more information on the state of the offshore wind industry, download your free digital issue of WorkBoat +Wind here.