The prospect of massive wind turbine arrays along the approaches to New York Harbor now seems very real, and advocates for maritime industries are raising their voices.

“Our ultimate goal is safety…we are the largest U.S. petroleum products port,” Edward Kelly of the Maritime Association of the Port of NY/NJ told a gathering of officials from the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management and state agencies Wednesday.

The association supports developing offshore wind energy and the jobs it would bring to the port, said Kelly. But it must be done right without increasing hazards in the East Coast shipping crossroads, he told a BOEM task force in Newark, N.J.

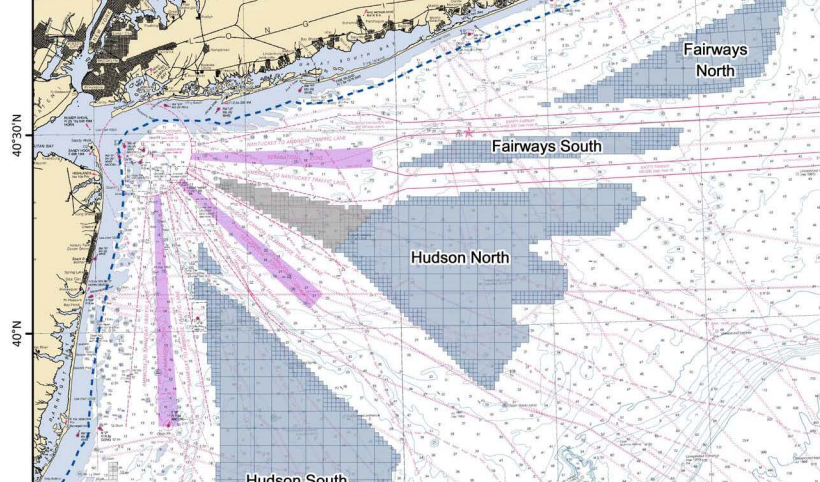

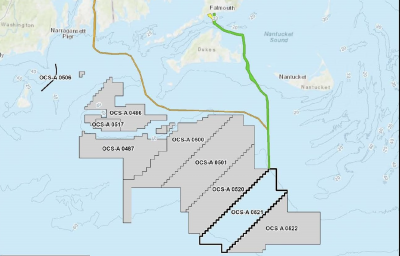

In a series of regional meetings BOEM is gathering information on its latest “call area” to consider expanding offshore wind energy leasing in the New York Bight, an arm of the Atlantic curved between New Jersey and New York’s Long Island shore, with the harbor entrance at its apex.

Wind power developers and federal energy planners have long seen the bight as an ideal location for developing wind farms.

Three critical factors are present, says Jim Bennett, who manages the BOEM renewable energy program: a shallow continental shelf for building turbines, dependable winds mostly from the northwest and southwest, and a needy energy market in the populous Mid-Atlantic and Northeast states.

Those populations need a lot of shipping too.

“We handle over 10,000 deep draft transits through that area every year,” said Kelly. “We feel the setbacks (from shipping lanes to turbines) are absolutely essential…we would like to have at least 1 nautical mile.”

“We cannot have any risk factor,” said Kelly, adding that any major accident like a ship allision with a turbine resulting in an oil spill would “have a generational impact.”

Tug and barge operators say the preliminary areas outline by BOEM are far enough offshore they don’t present an immediate conflict with their operations, said Brian Vahey, senior manager for the Atlantic region with American Waterways Operators.

There is some concern about how future wind leases might impede passages cutting across the Bight between Delaware Bay and New England. Extending more arrays eastward could force operators farther offshore and that could pose more risk in bad weather, said Vahey.

But overall in discussions with BOEM, “we’re optimistic that the process is good,” he added.

The ports of New York and New Jersey handle $205 billion of cargo annually, and are connected in trade to $50 billion out of Delaware Bay – a major petroleum shipping port with $50 billion – and similar values for Norfolk, Va., and Baltimore, Md., according to Coast Guard officials.

The Coast Guard is incorporating East Coast wind energy proposals – already some 11 areas leased by BOEM to developers already – into its Atlantic Port Access Route Study.

Meanwhile, containerships are getting bigger. Around thirty ultra large container ships now call at East Coast ports, and vessels bigger than those 14,000 TEU capacity ships could be coming.

Making space for all the traffic plus new wind farms could lead to cumulative effects on vessel traffic, and the Coast Guard converting longtime navigation corridors into new “shipping safety fairways” or other routing measures, said Chris Scraba, deputy waterways chief for the Coast Guard Fifth District in Portsmouth, Va.

One danger is that vessel density – ships operating within the same sea space – would be increased by the funneling effect of constricting traffic between turbine arrays. Another is the radar shadow effect of rotating turbine blades that can affect navigation radars.

Then there are the bigger containerships. At 1,200’x140’ “having to stop in a dime, there is no way for them to do that,” said Scraba. It can take an ultra large 2.5 miles of full astern to brake to a halt, he said.

Scraba compared the New York Bight traffic patterns to an interstate on land, like I-95 running up the East Coast. Part of the challenge is safely separating big and small, fast and slow vessels, he said.

But each wind farm and nearby ports will be different, so that will influence how appropriate buffers and setbacks are recommended to BOEM by the Coast Guard, said Scraba.

The stakes are high, he stressed.

“It’s critical we get this right,” said Scraba. “At the end of the day, we don’t have room for one accident, or one spill, in the New York Bight.”