Even as other states move faster, Maine has big potential to develop “next-generation” offshore wind energy technology with floating turbines, according to a new report by clean-energy advocates.

The American Jobs Project, a California-based nonprofit that promotes policies to create new U.S. manufacturing jobs in “advanced energy” including wind and solar power.

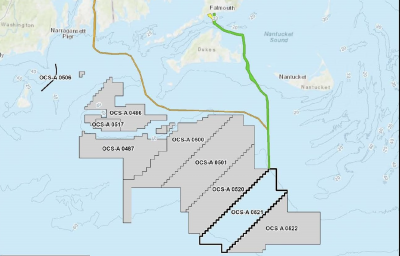

To the south, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New York and Maryland are all working to enable wind energy development on leases in nearby federal waters, with expectations that major wind power arrays will be up and running by 2030.

“Maine itself doesn’t have hard policy like that on the books,” said Ryan Wallace, director of the Maine Center for Business and Economic Research at the University of Southern Maine, helped the report authors with research and connecting to Maine businesses and groups.

From 2006 to 2009 the state’s long-range energy planning did have provisions for 5 MW of offshore wind in its long-range energy planning, and Norway-based Statoil considered a pilot project there using floating turbines.

That proposal ran into stumbling blocks, and then opposition from the administration of Gov. LePage. But Maine has something else: a decade-old project at the University of Maine to develop floating turbines that can be built onshore in the State of Maine and deployed in deep water offshore.

The university’s Advanced Structures and Composites Center developed the VolturnUS floating concrete hull technology to support wind turbines in water depths of 150’ or greater – much deeper than the shallow continental shelf areas that wind developers are working on to the south.

The Volturn model turbine, a 1/8 scale, 65’ tall machine deployed in Maine waters, became the first grid-connected offshore wind turbine in the U.S. in June 2013 – technically pre-dating the first commercial wind farm, Deepwater Wind’s Block Island array that went online in 2016.

“Next-generation floating turbine projects” could tap more powerful winds farther offshore, and help address the ocean planning issues to avoid conflicts with fishing and navigation, said Wallace.

Offshore wind could generate 2,000 new jobs annually through 2030, including direct and indirect employment, and build an infrastructure for new composites manufacture and use Maine’s existing concrete industry to build turbines and their floats on land, the report says.

The paper comes as Maine utility regulators review proposed electricity rates, including what would be paid for energy from a next-stage demonstration project.

The Maine Aqua Ventus I, GP, LLC group would build two 6 MW turbines on a Volturn semi-submersible hull south of Monhegan Island. The components would be assembled in Brewer and Searsport, and towed to the offshore test site. Anchored by three cables to the seabed, the turbines would be connected by an AC cable to Port Clyde.

The report contends Maine could climb on the same wind energy train as other East Coast states and recommends a number of policy steps – including a revival of the State Planning Office, which had worked on wind development but was dismantled in a cost-cutting move by the LePage administration.

“While Maine lags behind in comparison to Massachusetts and New Jersey and Rhode Island, I think that as momentum builds the industry is going to ramp up quickly,” said Wallace.

Now is a critical time because developers are looking for the most promising locations, he added.

“Policy is going to drive this, and if there is no consistency…they’re going to look elsewhere,” Wallace said. “If Maine’s not in the game, they can’t win."

---