An incoming administration under president-elect Joe Biden will bring strong support to the emerging U.S. offshore wind energy industry, likely paving the way for additional federal lease offerings, according to industry analysts.

“For the offshore wind industry, a President Biden is a far more positive development,” said Sarah Vilms of Squire Patton Boggs, a law and lobbying firm with offices in Washington, D.C.

With his intent to return the U.S. to the Paris climate agreement vacated by President Trump last week, climate policy “will be a defining” aspect of a Biden presidency, Vilms said during a Friday webinar hosted by the industry group Business Network for Offshore Wind, on the eve of U.S. media networks calling the 2020 election for the former vice president.

If Biden’s policy moves are blocked by a Republican-controlled Senate – now apparently dependent on runoff elections for Georgia’s two Senate seats – Biden like former president Barack Obama will likely resort to his own executive orders, said Vilms: “We expect him to use that power.”

That could foreshadow a re-run of dueling executive orders from the Obama and Trump presidencies, as when the Trump administration early on sought to undo Obama orders restricting Arctic ocean energy leasing.

Biden might exempt wind power development from President Trump’s executive order calling a moratorium on ocean energy leases from Florida to North Carolina, announced in the waning days of his re-election campaign.

The Trump administration itself has thrown out mixed signals on offshore wind for four years. Trump himself belittles wind energy, probably influenced by his personal experience trying to block an offshore energy project near a golf club he owns in Scotland, said David LesStrang of Squire Patton Boggs, a former Congressional subcommittee staff director.

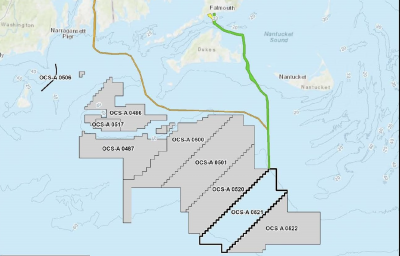

Meanwhile, the Department of Interior and its Bureau of Offshore Energy Management forged ahead on planning and granting wind energy leases, with 15 projects now planned off the U.S. East Coast. The agency is well underway for planning new wind energy areas off California and Oregon.

“Regardless of the (election) outcome, offshore wind in the United States has a very promising future,” said Liz Burdock, president and CEO of the Business Network for Offshore Wind. “Aggressive climate change policies at the state level” are largely driving the momentum, she said.

There is now bipartisan recognition of renewable energy potential, said LesStrang.

“Republicans have supported basically an all-of-the-above approach,” said LesStrang. “There seems to be now acceptance on both side of the aisle that renewables can compete with fossil fuels.”

Alongside climate policy, environmental justice for under-represented communities has been another goal for the Biden campaign, and U.S. fishermen could use that to make their case for a bigger proactive role in planning wind energy areas, Vilms suggested.

A Biden administration could bring more outreach to fishing communities, she said: “I see Biden striking a good balance there.”

“The environmental justice narrative is something that plays well on the Eastern seaboard of the United States,” LesStrang added.

One thing offshore wind developers should not expect is any big change to the Jones Act, the 1920 law that gives U.S.-flagged vessels and mariners preference for working on the nation’s waters.

Jones Act requirements are a growing source of friction between offshore wind developers – including European-based companies, who say the U.S. industry will need foreign flag installation vessels and expertise to get started – and longtime U.S. offshore services companies who want lawmakers to ensure domestic job creation is a priority.

Getting Congress to make changes is “an incredibly tall hill to climb,” said Emily Higgins Jones of Squire Patton Boggs, who noted the late Sen. John McCain of Arizona was unsuccessful for years in trying to build a consensus for Jones Act amendments. “I think it’s going to be a tough nut to crack.”

International energy analysts Wood Mackenzie predict a sharp policy pivot after Biden takes office. A new administration will act faster to help coastal states develop wind power, but over time will constrain offshore oil and gas development, according to Ed Crooks, the firm’s vice chairman for the Americas.

“There will not be a ban on fracking, but Biden has pledged to end sales of new leases for oil and gas development on public lands and waters,” according to Crooks. “Onshore, the impact would be minimal. Offshore, the effects would be more significant, although they would take some time to become apparent. A ban on new leasing, if permanent, would mean that by 2035 US offshore oil and gas production would be about 30 percent lower than if lease sales had continued.”

Similarly, Woods Mackenzie analysts estimate a Biden administration could boost offshore wind turbine construction in U.S. waters by 30 percent by 2030 compared to what a second Trump administration would do.

With the offshore oil industry battered by low prices and lower demand, all opportunities look good to U.S. offshore service operators.

“While the political landscape may look different after today, the promise of American energy remains constant. From offshore wind projects along the Atlantic Coast to oil and gas production in the Gulf of Mexico, the benefits of American energy production lift every American, regardless of party,” Erik Milito, president of the National Offshore Industries Association, said in his group’s statement. “NOIA congratulates President-elect Biden on his election win and looks forward to working with his administration and the incoming Congress.”