The Department of Interior’s review of the potential cumulative impact of East Coast offshore wind energy development is officially due in early 2020.

Despite some speculation that process could go on for some months later, industry advocates say the nascent U.S. industry’s momentum is continuing, with new contracts and commitments, and expectations of new Bureau of Offshore Energy Management offshore lease sales in the New York Bight and California waters.

“In 2020 we’ll have additional leases coming on line in New York and California. This will become a bicoastal industry,” Liz Burdock, president and CEO of the Business Network for Offshore Wind, told audiences at the 40th annual International WorkBoat Show in New Orleans last week.

While BOEM controls the granting of offshore leases, “the states are feeding the market,” with their ambitious plans to dramatically boost renewable energy supplies, said Burdock. Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey and others are seeking offshore wind as a replacement as aging fossil fuel and nuclear power stations are phased out in the Northeast.

The process of permitting as many as 15 federal waters leases is on a pause along with a BOEM environmental impact statement on the Vineyard Wind project off Massachusetts, as the agency examines the potential impact of building those turbine arrays on the environment and other maritime uses.

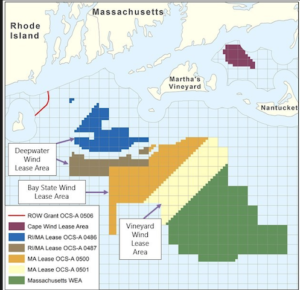

Vineyard Wind plans to build its 800-megawatt project (in yellow) 15 miles south of Martha's Vineyard. BOEM image

Interior Secretary David Bernhardt ordered that review after the National Marine Fisheries Service refused to sign off on the Vineyard Wind impact statement, the target of commercial fishing advocates who say the effect on both the environment and their industry are being underestimated.

The review is in effect “a tap on the brake” by Interior officials and is likely to the long-term benefit of the wind industry, said Ross Tyler, a senior developer with RWE Renewables.

“It’s better that we have this review at this point, than when we have two or three utility-scale projects underway,” said Tyler, until recently the vice president of the Business Network for Offshore Wind. “This will clear.”

Both Burdock and Tyler say the review pause gives some breathing space for more U.S. companies to get involved in planning for offshore wind projects and the domestic supply chain it needs to develop, apart from the global industry’s northern European roots.

“I actually see this as a positive,” said Burdock. “We were moving so quickly that a lot of U.S. businesses were not able to jump in.

“We’re continuing to add projects,” she added. “This will be resolved.”

Connecticut is the latest entry this week, announcing it will buy 804 MW from Vineyard Wind if it builds its planned Park City Wind project, using Bridgeport, Conn., as its hub port. Burdock said that raises to 9,040 MW the potential now under development. Other states have boosted their ante of their future planning, like New Jersey which recently doubled its long-term goal to 7.5 GW.

Since starting with modest 1-megawatt turbines in the 1990s, European developers have installed 18.66 GW of capacity, and over the years employed a fleet of 570 vessels, from survey and construction vessels to crew transfer vessels and others used in continuing operations and maintenance, said Burdock.

By comparison, the East Coast states could have access to 23.6 GW from planned projects, said Burdock. “So that gives you a sense of what this market will be like.”

What would completed turbine arrays look like? Compared to around 3,000 offshore oil and gas rigs in the Gulf of Mexico, 4,534 turbines stand in European waters.

If East Coast projects now proposed reach fruition, Burdock estimated there could be 686 of the most powerful turbines now under development, GE’s 12 MW Halide machines.

If the first projects are built with smaller turbines in the early 2020s, then stepped up to 12 MW, Tyler foresees two phases ultimately building around 1,000 turbines.

For the maritime industry, that could put 266 vessels in various roles – crewboats, construction, safety and other missions – to work through the 2020s, said Jason Folsom, national sales director for turbine manufacturer MHI Vestas.

Those jobs will come from across companies working on those projects, said Burdock.

“Everyone thinks you have to go to the developers” for contracts, she said. “Turbine suppliers will be contracting for crew and installation vessels. The foundation suppliers will be doing the same thing.”

The sole operating U.S. offshore wind installation is the 30 MW Block Island Wind Farm off Rhode Island. But longtime Gulf of Mexico offshore operator Joseph A. Orgeron said it has validated his conviction that there is a big future in the industry.

Now business and technology developer for Second Wind Maritime based in Galliano, La., Orgeron told industry colleagues about his experience bringing Gulf of Mexico liftboats north to Rhode Island to work on the Block Island project.

After the relatively wide-open Gulf coast, working in New England was tricky, Orgeron recalled. After travelling up the East Coast and getting into Narragansett Bay, the liftboats faced the Clairborne Pell/Newport Bridge suspension span.

With their 235-foot high high jackup legs, and just 196 feet of air draft under the bridge, the liftboat operators had to work a careful transit plan with the Coast Guard.

So, the trick was to lower the legs some feet and “kind of do a limbo under the bridge,” Orgeron explained. “Fortunately, there’s about 115 feet of water under the bridge.”

Similar constraints face the industry at other Northeast ports too, and wind advocates and workboat providers said a lot of networking will be needed to organize construction.

Wind developers have long worried about finding enough equipment to establish the industry here. Block Island showed that the Gulf of Mexico industry can bring its combined experience and equipment to the game “as a cost-effective asset they hadn’t thought of,” said Orgeron.