If a boat makes a sound in the Arctic, will wildlife flee?

That’s not a rhetorical question but one that Arctic tourism operator Hurtigruten Svalbard has to deal with on multiple levels. As the eldest tour operator on the cluster of islands that reside about halfway between the northwest coast of Norway and the North Pole, the organization understands the impact their boat tours have on the landscape, which see wildlife ranging from walruses to seals to numerous types of whales flee when hearing the roar of their engines from hundreds of feet away. That scattering of wildlife runs counter to the audience experience the organization seeks to provide, as well as to their commitment to sustainable tourism.

A desire to change how visitors can experience these natural wonders while also transforming values that are the foundation of their business led to the creation of the Kvitbjørn, a brand-new closed hybrid boat. Designed for exploration in the heart of the Arctic, the 14.6mX4.2m (48'x13.8'), 12-passenger Kvitbjørn (translation: Polar Bear) is powered by a complete helm-to-propeller Volvo Penta twin D4-320 DPI Aquamatic hybrid-electric solution. Integrated into a Marell M15, the Marell and Volvo Penta teams worked together to create a solution that would provide the ultimate sightseeing experience while also advancing sustainable solutions at sea.

A desire to change how visitors can experience these natural wonders while also transforming values that are the foundation of their business led to the creation of the Kvitbjørn, a brand-new closed hybrid boat. Designed for exploration in the heart of the Arctic, the 14.6mX4.2m (48'x13.8'), 12-passenger Kvitbjørn (translation: Polar Bear) is powered by a complete helm-to-propeller Volvo Penta twin D4-320 DPI Aquamatic hybrid-electric solution. Integrated into a Marell M15, the Marell and Volvo Penta teams worked together to create a solution that would provide the ultimate sightseeing experience while also advancing sustainable solutions at sea.

The team at Volvo Penta invited members of the media out to Svalbard for the formal unveiling and first official voyage of the Kvitbjørn to determine whether or not they succeeded with both. Along the way, we were able to explore what such commitments and customizations can mean for others that are exploring their own hybrid opportunities and how new business models can change an entire way of doing business.

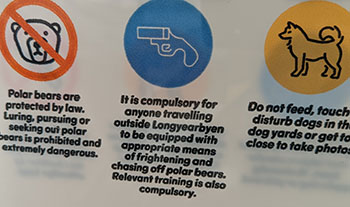

Oh, and we also found out that carrying a gun in Svalbard is not just recommended but mandatory due to the threat of polar bear attacks. Lessons on every level but none as relevant as the ones related to what this environment says about changes that are just around the corner for individuals and the maritime sector as a whole.

Oh, and we also found out that carrying a gun in Svalbard is not just recommended but mandatory due to the threat of polar bear attacks. Lessons on every level but none as relevant as the ones related to what this environment says about changes that are just around the corner for individuals and the maritime sector as a whole.

The world’s northernmost town

To say that Svalbard is like another world doesn’t convey the sense that the uninitiated get when flying over and then landing in a place that doesn’t just look cold but is literally frozen in the warmest of times. This Norwegian archipelago is only about 800 miles from the North Pole, which means temperatures well below freezing are normal in the winter months while the average summer water temperature is around 0°C. The largest settlement is Longyearbyen that has a population of just over 2,000 people, enabling it to become known as the world’s northernmost town.

That small number of human beings has allowed the native animal population to remain relatively stable, with signs warning of polar bears being an especially stark reminder that this world still belongs to those animals. They’ve become a popular spot for tourists to take photos, although posing with such signs is just one of the many activities available to them.

That small number of human beings has allowed the native animal population to remain relatively stable, with signs warning of polar bears being an especially stark reminder that this world still belongs to those animals. They’ve become a popular spot for tourists to take photos, although posing with such signs is just one of the many activities available to them.

That’s for good reason since the local economy is primarily geared towards tourism and scientific research. While year-round coal mining operations defined Longyearbyen in the early 20th century and continue to be the biggest industry on Svalbard, the last coal mine in operation is set to shut down in 2023. The future of the town is very much connected to the tourism industry but it’s a tricky needle to thread. Too much growth can ruin the appeal of such locations not to mention the settings themselves. In a place that’s as serene and untouched as Svalbard, finding that balance is essential.

Doing so is exactly what Hurtigruten Svalbard is prioritizing in the short and long-term. As a full-service provider of experiences that make Arctic dreams a reality, the organization offers everything from dog sledding to kayak paddling to ice caving to skiing expeditions. The Hurtigruten team knows better than anyone how such experiences can tax these same landscapes though, an understanding of which drove their commitment to sustainable tourism. This ethos is designed to take into account the effect that tourism has on the current and future economic, social and environmental impacts of visitors.

Doing so is exactly what Hurtigruten Svalbard is prioritizing in the short and long-term. As a full-service provider of experiences that make Arctic dreams a reality, the organization offers everything from dog sledding to kayak paddling to ice caving to skiing expeditions. The Hurtigruten team knows better than anyone how such experiences can tax these same landscapes though, an understanding of which drove their commitment to sustainable tourism. This ethos is designed to take into account the effect that tourism has on the current and future economic, social and environmental impacts of visitors.

“Our ambition is to be the most sustainable travel operator in the world,” said Henrik Lund, managing director of Hurtigruten Foundation. “That’s not the cheapest way of doing business, but it is the best way. It would have been easier for us to buy a regular boat but it wouldn’t have been the right thing to do. Our commitment to sustainability is engrained in everything we do which means it can’t just stay in a slide deck.”

Their commitment to sustainability partially drove initial conversations with the Volvo Penta team but considering the impact to the way they operate today was also a priority. Boat tour operators could see the sound of their engine caused the wildlife to scatter, preventing guides from being able to showcase the true wonders of Svalbard. The relative silence of the electric motor changes these experiences for the better, which was something that was front and center on the maiden voyage of the Kvitbjørn.

Connecting sustainability and innovation

Climbing aboard a ship that is moored next to others that looks as if they’re completely iced over contributes to the otherworldly experience of Svalbard. Mountains that look like they’re made of snow loom on every side, and the slightest breeze is something you end up feeling in your bones. My personal approach to fashion is to be able to wear the same thing inside as I do outside but that does not work on any level in Svalbard. And especially not when you’re out on the Artic Ocean, with nothing but the water and weather.

Climbing aboard a ship that is moored next to others that looks as if they’re completely iced over contributes to the otherworldly experience of Svalbard. Mountains that look like they’re made of snow loom on every side, and the slightest breeze is something you end up feeling in your bones. My personal approach to fashion is to be able to wear the same thing inside as I do outside but that does not work on any level in Svalbard. And especially not when you’re out on the Artic Ocean, with nothing but the water and weather.

That sense of calm and cold is the core experience of Svalbard though, which the Hurtigruten Svalbard understands. With a top speed of 30 knots, a cruising speed of 24 knots, the boat effortlessly moved out toward what looked like the endless mountains of the archipelago, all of which our guide was able to name. But the shift to silent cruising when we were able to get out on deck and see everything took it to another level.

Out in the middle of nowhere aboard the Kvitbjørn, you can literally hear the ice bob in the water. A walrus that was taking a break on the ice shore didn’t dive into the water. Birds seeming to skim across the water were on every side. All of which provided a sense of not just seeing these settings but actually being part of them. That difference is something the Hurtigruten team understood and knew they could further cultivate.

Out in the middle of nowhere aboard the Kvitbjørn, you can literally hear the ice bob in the water. A walrus that was taking a break on the ice shore didn’t dive into the water. Birds seeming to skim across the water were on every side. All of which provided a sense of not just seeing these settings but actually being part of them. That difference is something the Hurtigruten team understood and knew they could further cultivate.

“We almost did a deal with Marell for a regular drive train but then we met with the Volvo team to explore the option to have something more sustainable, but also something that made business sense,” said Tore Hoem, adventures director at Hurtigruten Svalbard. “To us though, it was really about the guest experience. And the key is silence. The silence is the coolest thing about it.”

That focus on audience experience is connected to what Hoem mentioned with the product making business sense. The deeper commitment to sustainability that the company prides itself on is evident in Svalbard, where you can see why this ecosystem is one that needs to be respected, cared for and preserved. At the same time, providing a better experience makes business sense because it means customers will keep coming back and recommending said trips to friends and colleagues.

That focus on audience experience is connected to what Hoem mentioned with the product making business sense. The deeper commitment to sustainability that the company prides itself on is evident in Svalbard, where you can see why this ecosystem is one that needs to be respected, cared for and preserved. At the same time, providing a better experience makes business sense because it means customers will keep coming back and recommending said trips to friends and colleagues.

Being able to cultivate these new experiences was a technology question that was addressed in those initial meetings between the Hurtigruten and Volvo Penta teams but the connection between technology and core business values runs deeper for both teams.

“We believe that sustainability and innovation are connected,” said Johan Inden, president of the Volvo Penta marine business unit. “Innovation comes from being able to understand the use case and then being able to design for it. This boat was designed for the Arctic waters of Svalbard but how would this hybrid solution need to be different than just another drivetrain? Those weren’t answers that we had when we began the initial conversations, but we’re committed to testing and learning what can work anywhere and everywhere. If we’re not trying, we’re not going to get there.”

Getting there is related to a bigger goal of the organization. Part of larger Volvo Group, Volvo Penta’s vision is to become a world leader in sustainable power solutions, with a vision to be a net-zero emissions company by 2050. Their full-systems approach is not just about more sustainability but higher performance, which is the only way that vision for sustainability will become a reality. That means the technology has to not only create quantifiable efficiencies but be reliable in a very practical sense. The capability and reliability of this technology gets pushed to the limit in Svalbard.

“We’re operating in such a harsh environment, where everything has to work.” said Jonas Karnerfors, sales project manager at Volvo Penta from the deck of the Kvitbjørn. “We needed to think more carefully about the job to be done, which is why we knew we had to create something that would seamlessly shift between driving modes. That connects back to the experience though, because when the boat is operating silently it’s operating in a much more sustainable manner. If it works here it can work everywhere.”

“We’re operating in such a harsh environment, where everything has to work.” said Jonas Karnerfors, sales project manager at Volvo Penta from the deck of the Kvitbjørn. “We needed to think more carefully about the job to be done, which is why we knew we had to create something that would seamlessly shift between driving modes. That connects back to the experience though, because when the boat is operating silently it’s operating in a much more sustainable manner. If it works here it can work everywhere.”

Connecting innovation and sustainability isn’t just about technology though, as this project also marked the debut of an e-mobility-as-a-service’ model from Volvo Penta. Designed to soften what are otherwise very high upfront payments typically associated with electromobility solutions, the model will see Hurtigruten pay a monthly fee depending on how much they actually utilize the drivetrain, which is something the Volvo Penta team considered in great detail.

“The price of this technology is higher so we knew we needed to better understand the business model,” Inden continued. “Is there a service model? Is there a rental model? We decided it’s not just a technology platform. It gives us a shared risk and joint responsibility. We are responsible to upgrade or make changes so we more fully determine how this can be used on commercial size. So we’re not only testing the technology with this but also testing brand new business models.”

Although it’s still at a concept stage, news about and developments related to this model could end up changing how these solutions are approached and adopted. If the cost isn’t what’s standing in the way of someone fully exploring the opportunities that are associated with hybrid-electric vessel technology, then what is? That’s the question this model will put squarely in front of owners and operators who might not be operating in the Arctic but will need to determine if the capability and reliability that hybrid technology has demonstrated makes sense for them this year and beyond.

Although it’s still at a concept stage, news about and developments related to this model could end up changing how these solutions are approached and adopted. If the cost isn’t what’s standing in the way of someone fully exploring the opportunities that are associated with hybrid-electric vessel technology, then what is? That’s the question this model will put squarely in front of owners and operators who might not be operating in the Arctic but will need to determine if the capability and reliability that hybrid technology has demonstrated makes sense for them this year and beyond.

Taking the long view of such challenges is easier to do in a place like Svalbard, where the stakes associated with decisions being made today can literally be experienced. Avoiding chunks of ice in electric mode makes all the difference in the world but it’s impossible to not think about the experiences that others can and will have in this same environment. Enabling those future experiences is something the Hurtigruten team is dedicated to, highlighting what it means to properly consider all the options that the technology represents.

A challenge to the maritime industry

The investment that Hurtigruten has made in hybrid technology is tied to the experiences they can now enable but also to ensure they aren’t behind the curve. Their customers expect and often push for greener solutions which has compelled them to set a benchmark that could soon become a new industry standard. This sort of standard needs a collaboration between owners, users and stakeholders though and it isn’t about a specific piece of technology or use case. New technology changes behavior, and while this solution is specific to short, dedicated journeys, there’s a bigger push for it to be an enabler for many different types of commercial marine operations. What exactly that looks like will depends on how this technology can fit into a specific vessel or operation, which will require active collaboration that many are pushing to see.

The investment that Hurtigruten has made in hybrid technology is tied to the experiences they can now enable but also to ensure they aren’t behind the curve. Their customers expect and often push for greener solutions which has compelled them to set a benchmark that could soon become a new industry standard. This sort of standard needs a collaboration between owners, users and stakeholders though and it isn’t about a specific piece of technology or use case. New technology changes behavior, and while this solution is specific to short, dedicated journeys, there’s a bigger push for it to be an enabler for many different types of commercial marine operations. What exactly that looks like will depends on how this technology can fit into a specific vessel or operation, which will require active collaboration that many are pushing to see.

“We want to challenge the industry with this solution,” Inden said. “That challenge isn’t about saying that hybrid solutions have to be adopted over the next two years or something prescriptive like that. Our challenge is about compelling vessel owners to really look at what they’re doing and work to transform an entire industry into something more sustainable that also make business sense for them. With new payment models we believe we can support this transformation that directly connects to being a net-zero emissions company by 2050. That isn’t our vision for the future, it’s our plan.”

“We want to challenge the industry with this solution,” Inden said. “That challenge isn’t about saying that hybrid solutions have to be adopted over the next two years or something prescriptive like that. Our challenge is about compelling vessel owners to really look at what they’re doing and work to transform an entire industry into something more sustainable that also make business sense for them. With new payment models we believe we can support this transformation that directly connects to being a net-zero emissions company by 2050. That isn’t our vision for the future, it’s our plan.”

Sitting less than 1,000 miles from the North Pole in a boat that is using electric power to maneuver through a field of ice, surrounded by wildlife that allows you to get right next to it, it’s simple enough to understand the stakes of that transformation, both in the short term and long term.

Just as the sign about polar bears mentioned though, properly preparing for a transition is on individuals. It’s the same whether you’re transitioning from the relative safety of Longyearbyen to the surrounding wilderness, or changing from the relative stability that powering systems have provided to the maritime industry to incorporate hybrid options. Heeding the warnings of literal or figurative signs that call out these transitions all comes down to the choices that people do or don’t make with tools that are readily available to them.