Shipyards told Congress Tuesday that they have the technical knowledge, workforce skills and construction experience to build the next generation of heavy icebreakers that will meet the growing U.S. maritime and security interests in the Arctic.

“There is strong interest in icebreaker construction from at least 10 shipyards located around the nation from the Northeast to California to the Northwest and again along the Gulf Coast and Great Lakes region,” Matthew Paxton, president of the Shipbuilders Council of America, told a House subcommittee hearing on the Coast Guard’s Arctic capabilities.

“The level of interest will ensure a robust level of competition for this project, which is certainly good for the Coast Guard and for the nation.”

Paxton said that although U.S. shipyards have not designed or built a heavy icebreaker in the past 40 years, the industry has delivered several other icebreakers during that period. The medium polar icebreaker Healy – built by Huntington Ingalls at its now-shuttered Avondale Shipyard in Louisiana – was put into service in 2000, and is actually larger than the Lockheed-built heavy icebreakers Polar Star and Polar Sea. The industry also built a smaller icebreaker for scientific research in 1992, the Great Lakes icebreaker Mackinaw in 2005, and the commercial icebreaking anchor-handling tug supply vessel Aiviq in 2012.

Industries that partner with shipyards also have the capability, equipment and technology to support building icebreakers, and the shipyard workforce is experienced in working with the steel thickness required for these heavy vessels. Paxton said many yards have built commercial containerships that require a steel thickness that is greater than that of icebreakers. “And many of our shipyards work in heavy steel construction beyond ships, building structures for nuclear power plants” that have even thicker steel requirements.

“Any notion that our industry could not handle the engineering and manufacturing of steel hulls rated at the highest polar codes for icebreaking just does not understand the capability of the domestic shipyard industry,” Paxton told the House subcommittee on Coast Guard and Maritime Transportation.

He said that once the Coast Guard has stable and validated requirements in place, it would take about seven-and-a-half years to build a new icebreaker, from start of concept design and construction to delivery.

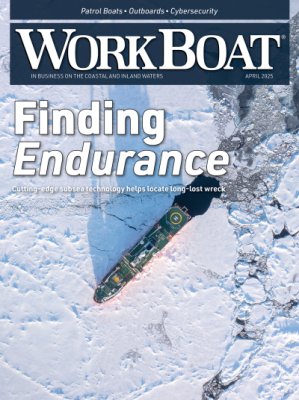

Global interest in maritime traffic in the Arctic has intensified as the summer sea ice levels have reduced, making the area navigable for longer periods. There’s also strong interest in exploration for oil, gas and minerals. This has prompted the Coast Guard to develop a strategy to meet mission demands in the region, and has highlighted the age and inadequate condition of the heavy polar icebreaking fleet to meet the new responsibilities. A recent study by the Government Accountability Office said that there will be a three- to six-year gap in heavy icebreaking capability before a new icebreaker is operational.

Rep. John Garamendi, D-Calif., said Congress must work over the next few months to set a policy to authorize and build two to three heavy icebreakers and two to three medium icebreakers. This should be done before the end of the year so that the new Congress and new administration have a policy in place going forward, Garamendi recommended.

President Obama has requested $150 million to fast-track construction of a new icebreaker, and the Senate Appropriations Committee recently included $1 billion for the first ship in the Defense Appropriations bill.

Garamendi concluded the hearing by saying that when it comes to building icebreakers, there’s no question that “we will make (them) in America.”