Recent detailed proposals from the Fisheries Survival Fund and Responsible Offshore Development Alliance – coalitions of the commercial fishing industry – and the American Clean Power Association representing the offshore wind industry, presented the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management priority lists for their industries’ coexistence.

Some of those recommendations distinguish between ‘mitigation’ – avoiding conflicts between wind development and fishing – and ‘compensation’ – paying to make up for fishermen being displaced from longtime fishing grounds.

Fishing advocates say BOEM should be following a “mitigation hierarchy” under the National Environmental Policy Act to “avoid, minimize, mitigate and compensate” for impacts of offshore wind development.

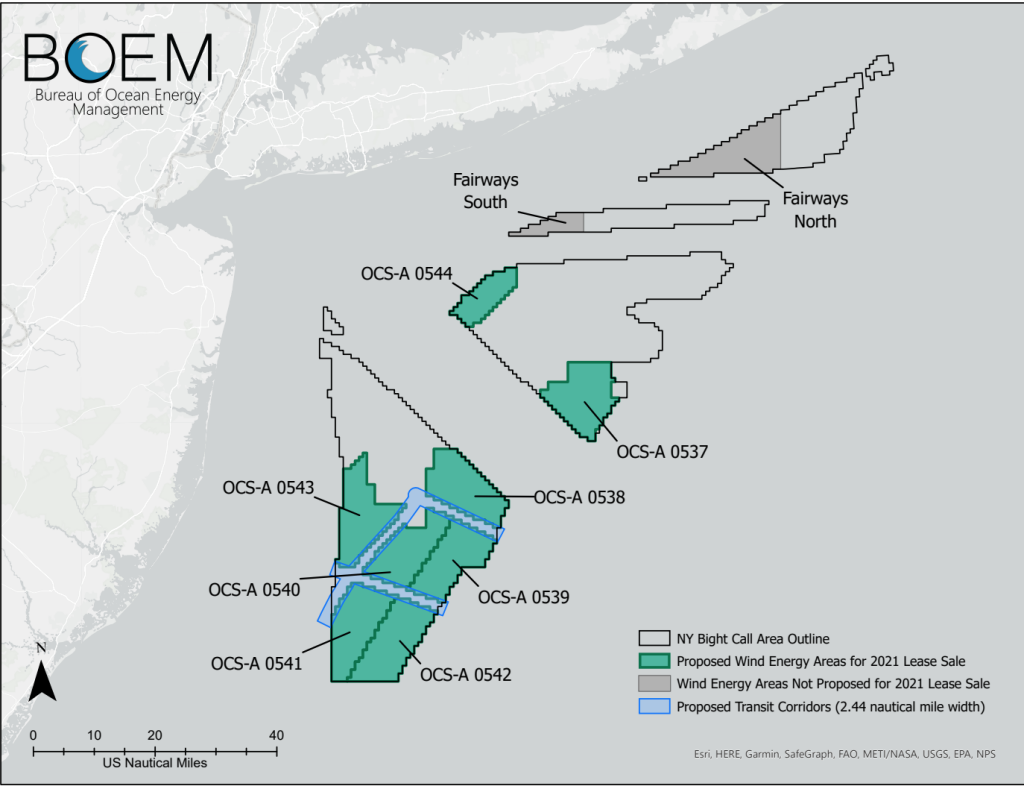

BOEM officials and wind energy advocates say that’s being done. As examples they point to modifications to the South Fork Wind project east of Montauk, N.Y., to preserve critical bottom habitat, and shifts in the New York Bight wind energy lease areas to reduce conflicts with the scallop fleet.

But the progress of BOEM’s permitting process overall is too light on avoiding conflicts at the start, said Mike Conroy, executive director of the Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen’s Associations. “They really seem to be skipping over the first three steps and stressing compensation. They view compensation and mitigation as interchangeable.”

On the West Coast, “it is still shocking to me how few people out here are really paying attention … whether it’s because they don’t realize what’s coming, or they’re hoping it goes away,” said Conroy, who is in the midst of putting together fishermen’s comments to BOEM on the proposed 206-square-mile Humboldt wind energy area off northern California.

“We’re being asked to comment on theoreticals,” with the future effects of wind arrays unknown and poorly researched, he said. “It’s not like you can tell people, ‘Hey guys, cool it for six or seven years and let’s see how these things work out.’”

If fishermen were to drop out, it could affect the viability of the West Coast’s small fishing ports. Without fishing business coming in, harbors and waterfront communities could not withstand intense pressure from recreational and real estate interests, said Conroy.

There’s worry that compensation offers early on could speed that and divide the industry, said Conroy.

“It all goes back to bad siting,” said Bonnie Brady, executive director of the Long Island Commercial Fishing Association. “The way to solve this is to keep these things off our fishing grounds.”

The Rhode Island Coastal Resources Management Council sought a more cautious approach going forward from the 30-megawatt Block Island Wind Farm that went online in late 2016, Brady recalled.

“The next logical step is to scale development up to a small utility scale project based on the lessons learned from the first step,” the council said in comments on the South Fork Wind project that Brady cites. “This allows proactive planning based on scientific best practices.”

The South Fork project as proposed was “exactly aligned with this desired progression in size and scope,” the council commented. “Nevertheless, the location of the SFW project on Cox’s Ledge, an area known for its biological diversity, is in our view one of the worst possible locations for this project.”

BOEM and the developers ultimately agreed to shuffle the layout for South Fork, reducing the number of turbines from 15 to 12. But Brady said turmoil between regulators, developers and fishermen could have been avoided earlier.

If it does come to compensating fishermen — an absolute last resort, in the view of Brady and other advocates — “here’s the solution,” she says.

In Denmark — home to much of the European offshore wind industry — “there’s a requirement as part of Danish fisheries law that all fishermen who fish in those (wind energy) areas must be compensated,” said Brady.

Setting up a fair and equitable system to do that must be built from the ground up, said Jim Kendall, a longtime scallop captain who now runs New Bedford Seafood Consulting.

“I along with others, strongly feel that the state, Massachusetts or any of the others should not be in charge of holding or distributing whatever funds are set aside for those purposes,” said Kendall. “The distributions should be handled by regional boards that would be designated to be responsible for area impacts and fisheries.”

A larger, or even smaller managing body, would be unlikely to have the expertise to handle larger coastwide fisheries, or properly represent fishermen who are not fishing at that time in its local waters, he said.