Offshore wind energy companies are contending with many of the same environmental issues as other maritime industries in U.S. waters, and on a compressed timeline.

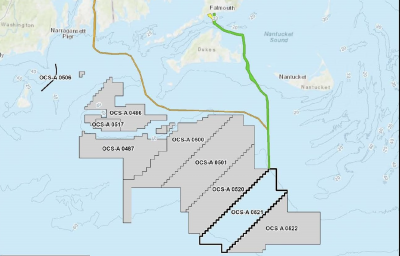

Pumped up by state policies encouraging renewable energy, and the Trump administration’s big buy-in to promote new domestic energy production, a dozen federal wind energy leases are already approved off the East Coast, and construction and operation plans for two projects are under review.

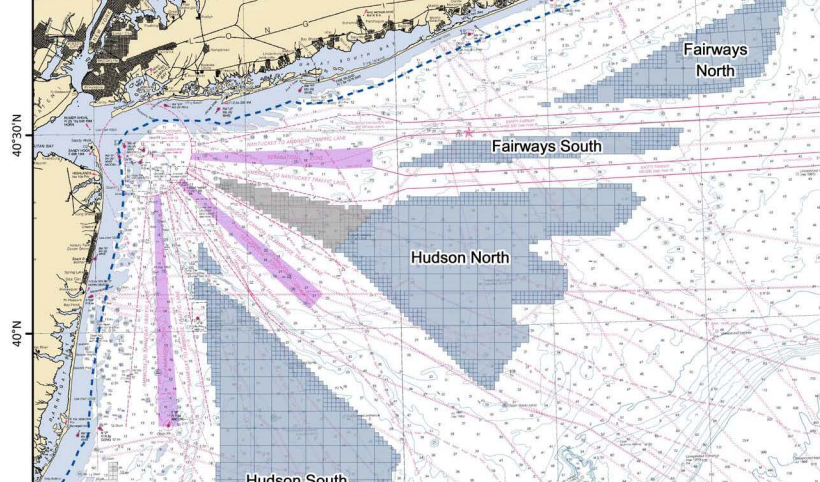

Deepwater Wind could have turbines on its South Fork Wind Farm off the east end of Long Island, N.Y., operational in 2020. The federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management says developers have plans for 8.5 gigawatts capacity of offshore wind power, with construction picking up pace through the 2020s.

Renewable energy advocates hail this as a train coming down the track. Fishermen want scientists’ help to at least slow it down.

“We’re really hoping to partner with the scientific community in this process,” lawyer Anne Hawkins told an audience at the American Fisheries Society annual meeting in Atlantic City, N.J., this week.

Researcher Matt Breece of Delaware State University holds an Atlantic sturgeon that was captured and released in April 2012 under NOAA-NMFS Endangered Species Collection Permit 16507. Kirk Moore photo.

Hawkins has represented scallop fishermen who say building wind arrays on the continental shelf threatens to shut them out of some of the richest shellfish grounds. This spring they and other seafood interests formed the Responsible Offshore Development Alliance, seeking to present a unified front in engaging the wind industry and government regulators.

Wind developers have more than the fishermen to deal with. There are endangered species out there where they would be driving piles and laying cables between turbine towers, from the northern right whale to the prehistoric-looking Atlantic sturgeon.

Brian Hook, a marine biologist with BOEM, described how the agency is getting help from sturgeon researchers to map out migration routes the fish use from the ocean to their spawning grounds in Chesapeake and Delaware bays and the Hudson River.

One effort at Delaware State University employs commercial fishermen to help researchers catch sturgeon and release them with acoustic tags – colloquially called pingers – that emit periodic signals so the fish can be tracked.

Those are helping BOEM seem migrations in time and space of the ocean – a critical factor in deciding where to site turbines and when to allow construction.

Much more research needs to be done, scientists say.

“In a few years we’re going to have a lot of construction, and that doesn’t give us much time to get the baseline down,” said Kevin Stokesbury, a fisheries professor at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth.