The government’s plunge toward creating more offshore wind energy areas in the New York Bight is looking like a repeat of its mistakes in planning southern New England projects and needs to be braked, fishermen said in a meeting Aug. 6 in New Bedford, Mass.

“It’s going to be responsible for the destruction of a centuries-old industry that’s only been feeding people,” Bonnie Brady, executive director of the Long Island Commercial Fishing Association, told officials of the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management.

“If you really want to do that right thing, stop everything” until wind energy areas can be better assessed to accommodate power generation while maintaining fisheries, said Brady.

Speaking with fishermen via a Zoom online link, BOEM Director Amanda Lefton opened the meeting by saying the agency has learned from experience and is working to engage better with the fishing industry and head off conflicts.

“We have to improve our engagement with the fishing industry,” said Lefton. “We are doing our best to makes changes.”

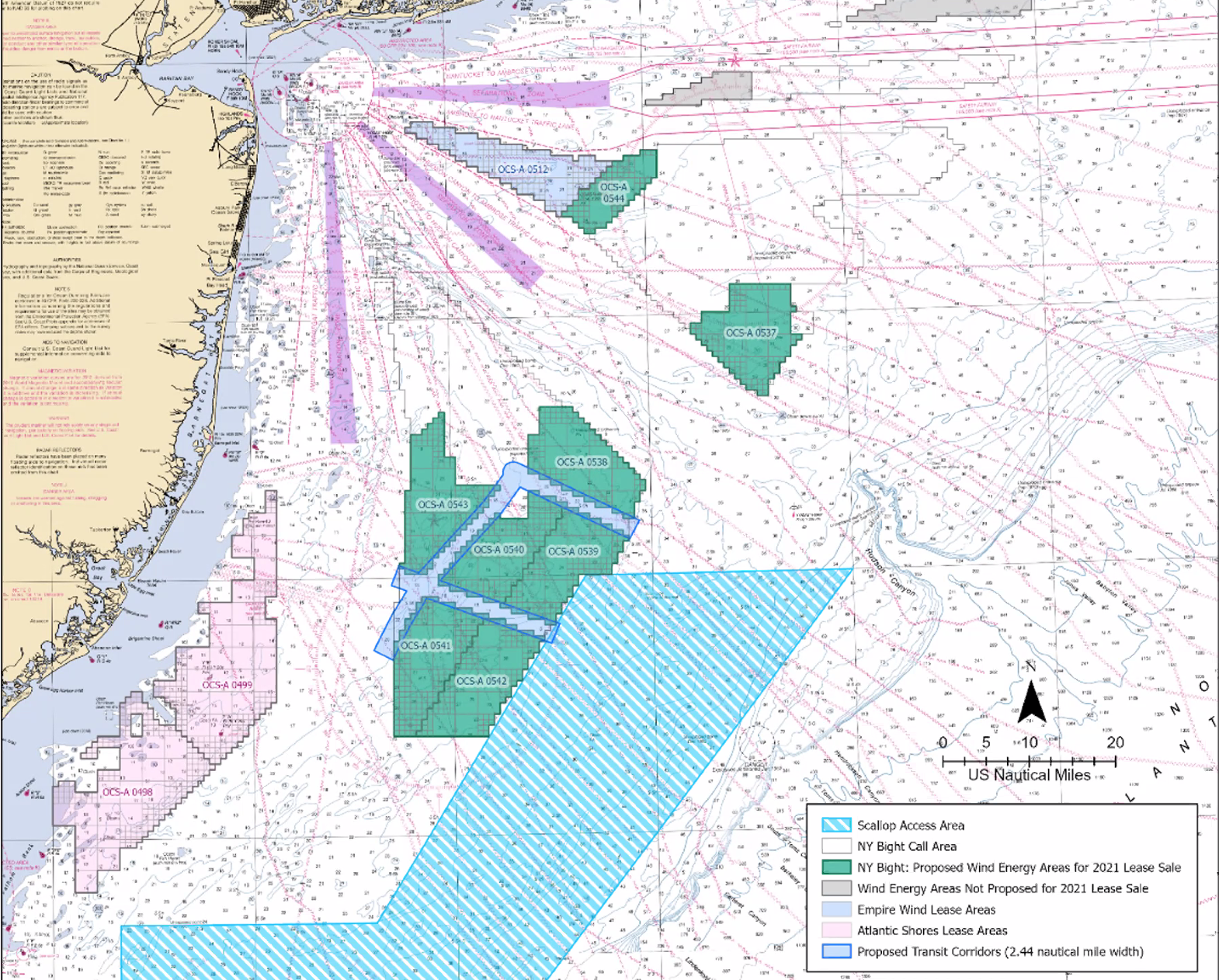

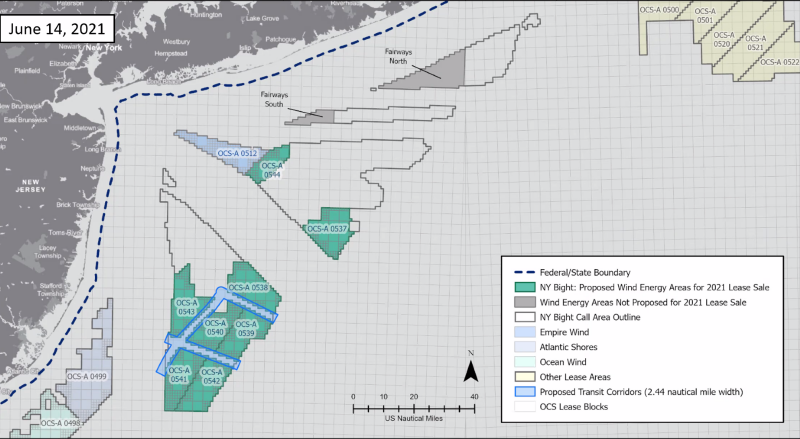

Some changes are coming in how BOEM will review plans for the New York Bight – the arm of the Atlantic between Long Island and New Jersey, adjacent to the voracious New York regional energy market and already targeted for major offshore wind projects.

Future new leasing will include requirements for wind developer to report more frequently and be more accountable for how they will deal with issues of environmental impact and effects on fishermen and other maritime users, BOEM officials said.

Fishermen said they are skeptical after seeing past performance by the agency and wind developers.

“When we give feedback…we want to see it taken seriously and put into the project,” said Katie Almeida, senior representative for government relations at The Town Dock, Point Judith, R.I. “We just need to see some of what we’re saying brought forward…and incorporated into wind farm planning.”

“We’ve only been asking for this for six years,” Almeida added. “This can’t be just going forward” with future leases, but should be applied to approved projects like Vineyard Wind and South Fork off southern New England, she said.

“I come at it from a legal standpoint…it seems like there’s a burden of proof,” said Blair Bailey, general counsel for the Port of New Bedford which hosted the meeting.

While fishermen’s detailed critiques and suggested changes have fallen by the wayside in planning, Bailey said objections from wealthy seaside communities have not. For example, New York State energy planners explicitly cited views from onshore Long Island in discounting potential sites closer than 18 miles.

“When someone doesn’t want to see a wind turbine from their house onshore, that area disappears,” said Bailey.

Fishing advocates urged BOEM to approach planning on a wide regional basis, saying the experience in southern New England has been project-by-project.

“It’s a divide-and-conquer approach, and it’s not a reasonable approach for a federal agency,” said Peter Hughes, general manager of Atlantic Capes Fisheries in Cape May, N.J.

BOEM is trying to do that better with the New York Bight wind energy areas, including proposed vessel traffic lanes, said Luke Feinberg, a project coordinator with the agency.

The need to think regionally should have been evident from the start, said Brady.

“I was the one who had to tell them there were like six other states (fleets) that fished there” from Virginia to New England, she said. “That’s where these guys live.”

Building the Vineyard Wind project will likewise have industry-wide impact beyond ports in its immediate vicinity, with up to 60 percent of East Coast squid catches coming from that area in some years, Brady added.

Surf clam and scallop fishermen said the deeper ecological and hydrological impacts of building potentially hundreds of turbines need intense study.

“Nothing has been done,” said Guy Simmons, senior vice president for marketing, product development, fisheries science and government at Sea Watch International, a major East Coast surf clam operator. Adding those new structures could alter the Mid-Atlantic cold pool, the seasonal stratification in ocean water temperatures that is a key factor in marine species’ life cycles, said Simmons.

“The currents around the turbines are exactly what breaks down the cold pool,” said Simmons, adding “they need to stop everything right now…until the proper environmental considerations” have been studied.

“We are taking a hard look at the hydrodynamic implications,” replied Brian Hooker, a marine biologist with BOEM, who added that scientists at the University of Massachusetts and Rutgers University are likewise investigating how new structures might change ocean conditions.

“We are going to die by monitoring,” Simmons replied. “We need to do the science ahead of time.”

“We know that when you put structure in the water you change currents,” said New Bedford scallop fisherman Eric Hansen.

Other effects from building towers and their rock-armored foundations will be increases in blue mussels – competitors to scallops for food in the water column – and scallop predators including moon snails and starfish, said Hansen.

The industry group Fisheries Survival Fund is recommending a 5-nautical-mile buffer between any future wind leases and the Hudson Canyon scallop access area, a resource that's been critical to the fleet's success over two decades.

“Right now, there’s a legitimate fear of the unknown,” said Hansen, “but we have to go slow before we ruin everything.” ,