Federal energy planners dropped two areas near Long Island from immediate consideration for offshore wind energy leases, citing potential conflicts with maritime traffic, fishing and seaside views from exclusive New York beach resorts.

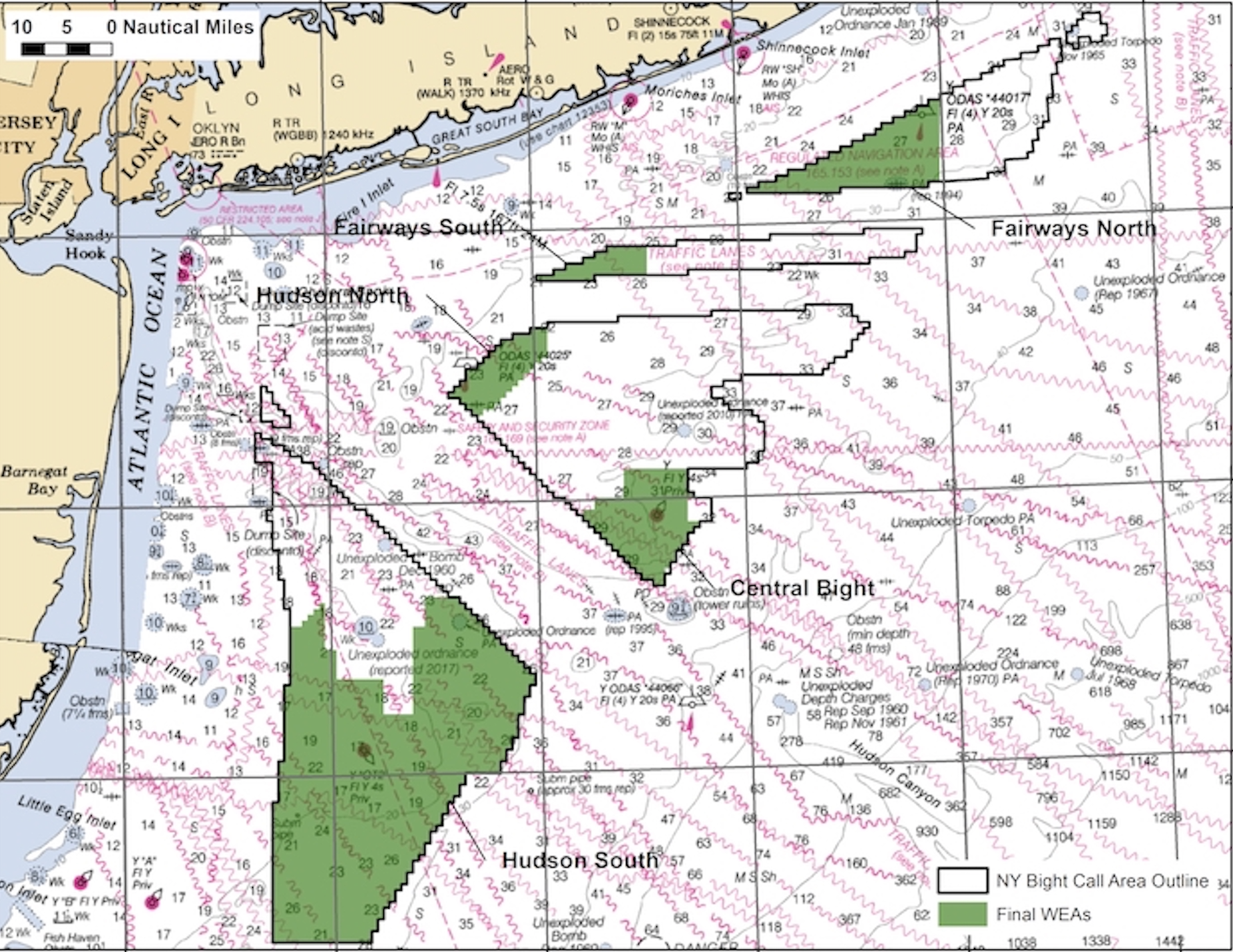

The Fairways North and Fairways South areas, named for nearby shipping approaches to New York Harbor, were also seen as less attractive to wind developers for their smaller power potential. Removing them from Bureau of Ocean Energy Management planning still leaves more than 627,000 additional acres in the region available for future lease sales.

New York State officials recommended against planning for leases in the Fairway areas, saying the closest 15-mile proximity to Long Island runs counter to the state’s policy of keeping wind generation at least 18 miles from shore.

The BOEM decision came as the agency commenced online meetings of its New York Bight task force, including federal, state and local government representatives and other stakeholders.

One prominent group not in virtual attendance Wednesday was the Responsible Offshore Development Alliance, a coalition of fishing groups and communities. The group has been meeting for years with BOEM planners and wind developers, but in recent weeks reacted with alarm to the Biden administration’s full-court press to expand the industry.

“Fishermen have shown up for years to ‘engage’ in processes where spatial constraints and, often, the actors themselves are opposed to their livelihood,” according to a letter RODA submitted to the task force.

“This time and effort has resulted in effectively no accommodations to mitigate impacts from individual developers or the supposedly unbiased federal and state governments,” the letter says. “Individuals from the fishing community care deeply but the deck is so stacked that they are exhausted and even traumatized by this relentless assault on their worth and expertise.”

While RODA chose to sit out this bout, the National Marine Fisheries Service was represented. The agency did not hold back on its view of potential environmental and fisheries impact should more wind energy areas be developed in the New York Bight.

The region “is one of the most important areas on the East Coast for commercial and recreational fisheries,” said Sue Tuxbury, a fisheries biologist in the agency’s habitat conservation division who works on wind energy and hydropower activities.

Surf clams and scallops, two of the most valuable East Coast fisheries, have major shellfish resources on the bottom. “The location and number of turbines” will be a major factor in whether those dredge fisheries can continue to operate around the wind areas, said Tuxbury.

She recommended that BOEM and the Bight task force consult RODA’s 2019 workshop on fishing vessel transit issues – and for the agency to hold new meetings with commercial fishermen to discuss potential traffic lanes for New Jersey ports Barnegat Light and Cape May, close to the planned Ocean Wind and Atlantic Shores turbine arrays.

Tuxbury said unknown environmental questions include how those arrays may affect the Mid-Atlantic cold pool, the seasonal stratification of water temperatures that is influential on the life cycles of fish and other marine life. New surveys and scientific modeling are needed to anticipate how those changes may happen and play out, she said.

BOEM’s proposed wind energy areas include essential fish habitat “for nearly every species” managed by NMFS and the New England and Mid-Atlantic fishery management councils, said Tuxbury. Building turbines out there “will directly impact” the agency’s ability to conduct at-sea scientific surveys that managers depend on to make decisions, she said.

Survey vessels operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration will likely be excluded from operating their trawl sampling gear in wind energy areas by spatial constraints between turbine towers. Along with the need for longer vessel transit times to get around arrays, that will reduce biological sampling, said Tuxbury.

Meanwhile wind power development will be altering the ocean habitat. BOEM, NMFS and other agencies need to plan now for mitigation measures to account for those changes, said Tuxbury.

The need for safe spaces between turbine towers and bigger ships was on the minds of maritime advocates too. George Detweiler Jr. of the Coast Guard navigation center described how planners are mulling various configuations for a tug and tow fairway to provide safe passage past turbine arrays between Cape May and Montauk Point.

“We’re very much in favor (of offshore wind power) like everyone on the planet should be,” said Ed Kelly, executive director of the Maritime Association of the Port of New York and New Jersey. “We have to insist it remains safe, secure and environmentally sound.”

Kelly said the recent Suez Canal blockage by the grounding of the ultra-large container vessel Ever Given shows the vulnerability of ULCVs to windage in tight passages.

Coast Guard guidelines now call for turbines to be set back two nautical miles from the edge of traffic separation zones into New York Harbor, and five miles from the terminus points of those lanes, said Arianna Baker, a BOEM specialist.

But near the northern apex of the bight, setbacks are just one nautical mile along the planned Empire Wind project, nestled between two lanes out of the harbor, said Andrew McGovern, a Sandy Hook pilot who serves on the harbor safety committee.

“These ships are getting bigger and bigger and there can be issues,” said McGovern. He recommended a minimum two-mile setback for all wind energy areas.

BOEM must work closer with other resources agencies including NMFS and the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission in planning projects, said George Fagan of the New Jersey-based environmental group Clean Ocean Action. Resetting those relationships would “take what has been an oil and gas agency into this new age of wind,” he said.