Building floating offshore wind turbines is already daunting. Designing floatation to support massive towers, anchoring systems and inter-array cabling requires new port facilities and a spiderweb off offshore infrastructure.

Then there are questions of how to bring that offshore energy onshore. A two-year study by the federal Department of Energy’ Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) and National Renewable Energy Laboratory examined how linking future offshore wind development to regional grids could help energy reliability in coastal communities and lower overall costs to power customers in the Western U.S.

“Offshore wind transmission can deliver a new source of power to support a significant portion of rising energy needs,” said Travis Douville, lead author on the report and an advisor at PNNL who leads research on integrating wind energy into the grid. “And even when the wind is not generating electricity locally, networked offshore transmission can still transport low-cost energy from onshore like solar, land-based wind, and hydropower.”

The report was published Jan. 15, amid a last push by the outgoing Biden administration to advance offshore wind and other renewable energy projects, now under attack by the Trump administration its allies in legacy fossil fuel industries. But the report’s long timeline scenarios could serve as a blueprint for a future revival of West Coast wind power.

The researchers estimate that growing electrical demand in the Western states – to power transportation, buildings and industry – will require an additional 400 gigawatts (GW) of generation capacity by 2050.

Their new report shows that floating offshore wind could supply 33 GW of that coming energy requirement by 2050 “and bolster the resilience of coastal communities,” according to a summary from the Pacific Northwest lab. “In some scenarios, the additional transmission that would be built to transport the offshore wind could also help to transport lower-cost energy like solar and hydropower, ultimately leading to billions of dollars in savings across the Western Interconnection.”

The design and building of transmission systems will be a major consideration and “more work needs to be done to ensure consumers receive maximum energy benefits at the lowest cost,” according to the PNNL.

“With careful planning and coordination across multiple points in time, we can solve the question of how offshore wind generation and transmission could be developed on the West Coast for maximum benefit,” said Douville.

Offshore southern Oregon and northern California with 10 to 50 miles of the coast is attractive for wind power planners for wind strength and consistency, an average 22 mph, according to the PNNL. Having offshore wind power at hand could improve energy reliability for coastal cities, the researchers wrote.

“With nearly every point we connect wind energy to the southern Oregon and northern and central California coast, there's immediately an energy resilience benefit from having a generator nearby because there aren't a lot of generators at the coast,” said Douville. “Though there are costs to incorporate bulk power flows at these points of interconnection, there are direct improvements in power quality and resilience of the local grid.”

The depths of the Pacific Ocean are an immense problem for building offshore wind, unlike most of the East Coast where the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management has focused on the relatively shallow outer continental shelf. The Pacific Northwest lab researchers limted their study to sea floor regions no deeper than 1,300 meters or 4,265’.

“We found that approximately 30 GW of offshore wind energy and transmission components could be deployed in economically favorable locations off central and northern California and southern Oregon,” said Greg Brinkman, a National Renewable Energy Laboratory co-author on the study. “To go beyond 30 GW in this region, waters to the west at greater depths, or north with lesser quality resource could be explored.”

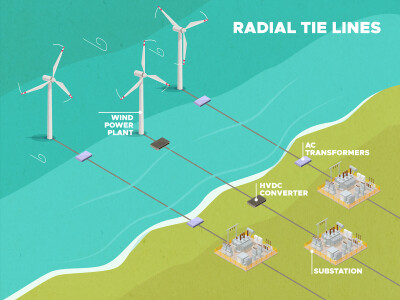

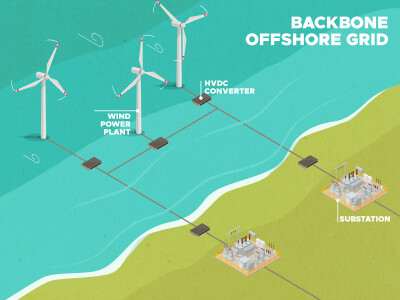

In examining how to transport power from the ocean to land, the team studied two transmission concepts: A “radial” structure, where each wind turbine array is connected to one point on the coast, and a “backbone” structure with arrays connected to each other in the ocean as well as to points on the coast.

“A backbone structure allows large grid operating regions to connect to each other,” according to the PNNL. “Although this scenario would cost more initially (because it would require building more transmission), the benefits outweigh the cost because it would ultimately allow cheaper energy to be transported more efficiently across regions.”

“Overall, the team found that starting with a radial structure in 2035 that would evolve into a backbone structure connecting grid operating regions provides the most benefits at the least cost. They estimated that after construction costs, savings could total $25 billion in today’s dollars mostly due to the ability to share lower-cost energy such as solar and hydropower across grid regions.”