Offshore energy developers and the U.S. maritime industry are locked in a renewed battle over legislation that would give preference to hiring U.S. workers, particularly in offshore wind power.

The Coast Guard Authorization Act of 2022 – ordinarily a calmly bipartisan effort in Congress every two years to approve Coast Guard operations and planning – passed the House of Representatives on Tuesday, March 29.

But wrapped inside the package is a section, sponsored by Reps. John Garamendi, D-Calif., and Garret Graves, R-La., that would require new crewing and reporting requirements on operators of foreign-flag vessels working in U.S. waters.

Backed by U.S. maritime companies and labor, the sponsors presented their “American Offshore Worker Fairness Act” as a measure to hold energy companies and their contractors closer to the Merchant Marine Act of 1920 – also known as the Jones Act, originally built to protect the domestic U.S. maritime industrial base.

“This bipartisan bill closes an egregious Jones Act loophole so that foreign-flagged vessels are held to the same high standards as US-flagged vessels developing our nation’s offshore energy resources, including for offshore wind projects,” Garamendi said March 2 when the amendment was accepted.

In its campaign for the legislation, the Offshore Marine Services Association stressed it would “change the current practice where foreign vessels utilize crewmembers from low-wage countries at day rates no American would or should accept. This unfair practice gives foreign vessels a competitive advantage over U.S. vessels and takes jobs away from American mariners.”

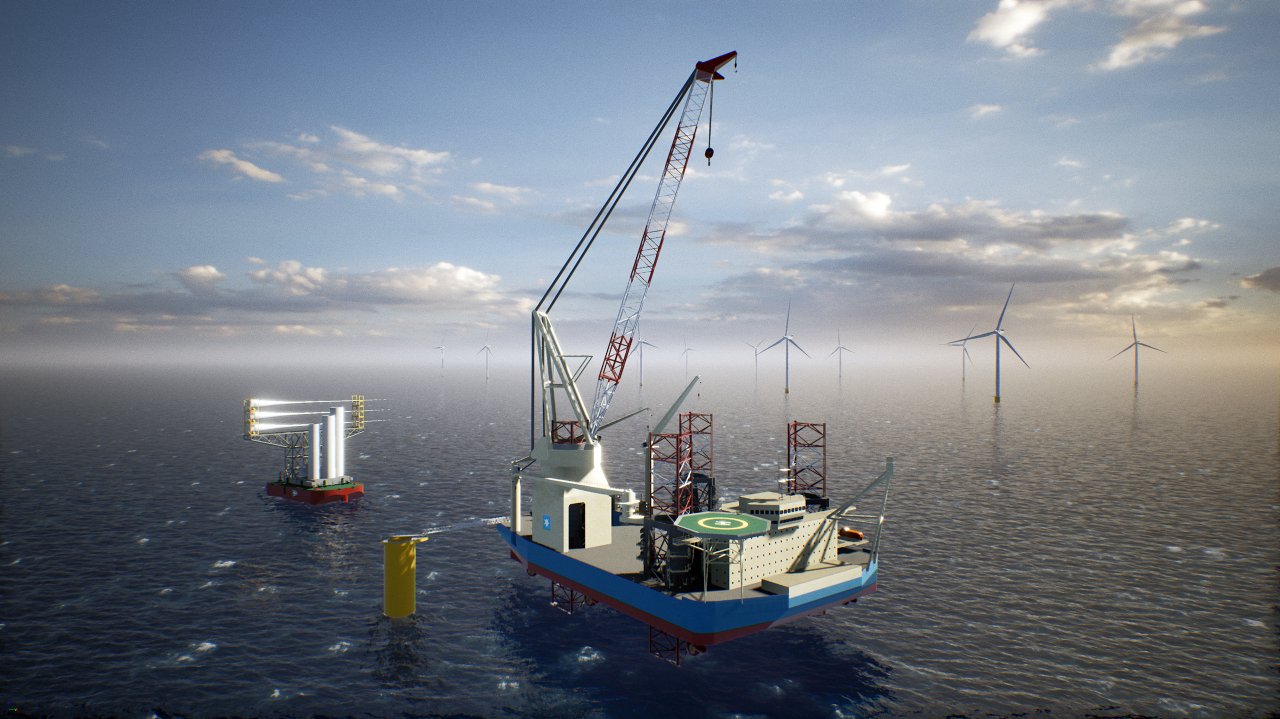

Offshore wind advocates are pushing back hard – and stressing the worldwide shortage of wind turbine installation vessels, which they say could hobble development of the U.S. wind industry for years to come.

The new fight erupted as Maersk Supply Service announced it will have a WTIV built in Singapore, to install the first phase of the Empire Wind turbine array near approaches to New York Harbor.

Maersk and Empire Wind partners Equinor and BP would work with Kirby Corp. subsidiary Kirby Offshore Wind, using newbuild Jones Act-compliant vessels to carry turbine components out to the project site.

Some in the industry contend the proposed crewing provisions will complicate those plans.

Vineyard Wind has a similar arrangement with Foss Maritime, for Jones Act-compliant tugs and barges to transport turbine components from shore to a foreign flag WTIV for assembly on the site of that 800-megawatt project off Massachusetts.

“If passed into law, this provision would prevent the U.S. from achieving the administration’s target of deploying 30,000 MW of offshore wind by 2030,” American Clean Power CEO Heather Zichal said in a prepared statement. “As the voice of industry, we remain committed to working with the U.S. Senate to stop this anti-jobs provision from being enacted and holding back our nation’s ability to produce more sources of clean homegrown energy.”

Zichal said “the maritime crewing provision as it will cripple the development of the American offshore wind industry.”

It’s a touchy subject for the offshore wind industry. Wind development companies based in Europe are always acutely aware of the higher costs for operating in U.S. waters under the Jones Act. On the other hand, developers and U.S. politicians are also closely allied with American labor unions, who anticipate many years of work at sea and on shore for their members – in both the maritime and construction trades – if the Biden administration’s goal of 30 gigawatts of wind power moves forward.

One ‘no’ vote on the Coast Guard bill came from Rep. Jake Auchincloss, D-Mass., whose Fourth Congressional District borders Rhode Island and the port of New Bedford, two centers for offshore wind development.

"Tonight, I voted with my district," said Auchincloss in a statement. "While I strongly support funding the Coast Guard, a hidden provision in this bill would grind offshore wind production to a halt, costing thousands of local jobs and impeding our ability to meet President Biden's clean energy goals."

According to the Offshore Marine Services Association, the Garamendi-Graves amendment “would change the current practice where foreign vessels utilize crewmembers from low-wage countries at day rates no American would or should accept.” OMSA says other changes will include:

• Requiring foreign mariners working in the U.S. offshore energy markets secure a Transportation Worker Identification Credential (TWIC). Current regulations allow such mariners the option to secure a TWIC while U.S. mariners are required to secure and hold a valid TWIC.

• Limiting the number of visas that can be issued for each foreign vessel operating in U.S. waters and takes steps to ensure that these visas are connected to the mariner’s work on that vessel. Requiring each foreign vessel in U.S. offshore energy markets to prove their ownership structure annually.

• Requiring the U.S. Coast Guard to annually inspect foreign-flagged vessels operating in U.S. offshore energy markets to ensure compliance with these changes.

The Maersk plan for building its WTIV in Singapore is certain to fuel debate over how much offshore wind may benefit the U.S. shipbuilding industry.

The sole U.S.-built WTIV so far, the 472’ Charybdis now under construction by Keppel AmFELS in Brownsville, Texas, has commitments for work beyond owner Dominion Energy’s own 2.6 gigawatt Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind project. It’s being closely watched as an indicator of whether other companies will decide to invest around $500 million in another Jones Act-compliant WTIV.