As the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management prepares for an environmental review of the Ocean Wind project off New Jersey, the prospect of seeing wind turbines arise on the horizon is raising alarms in prosperous resort towns.

Politically the state has been all-in on offshore wind, with $250 million planned for investment in manufacturing at the port of Paulsboro on the Delaware River, and plans for a new port downriver – beyond the air draft limitations of river bridges – to accommodate wind turbine installation vessels. A groundbreaking April 20 marked the start of construction for a monopile manufacturing facility at Paulsboro for steel fabricator EEW to make the foundation components for Ocean Wind.

The Biden administration’s policy imperatives for renewable energy include a dramatic expansion of new wind leasing in the New York Bight. Ocean Wind, a 75/25 percent joint venture of Ørsted and the PSEG utility group, could be sending power ashore in 2024.

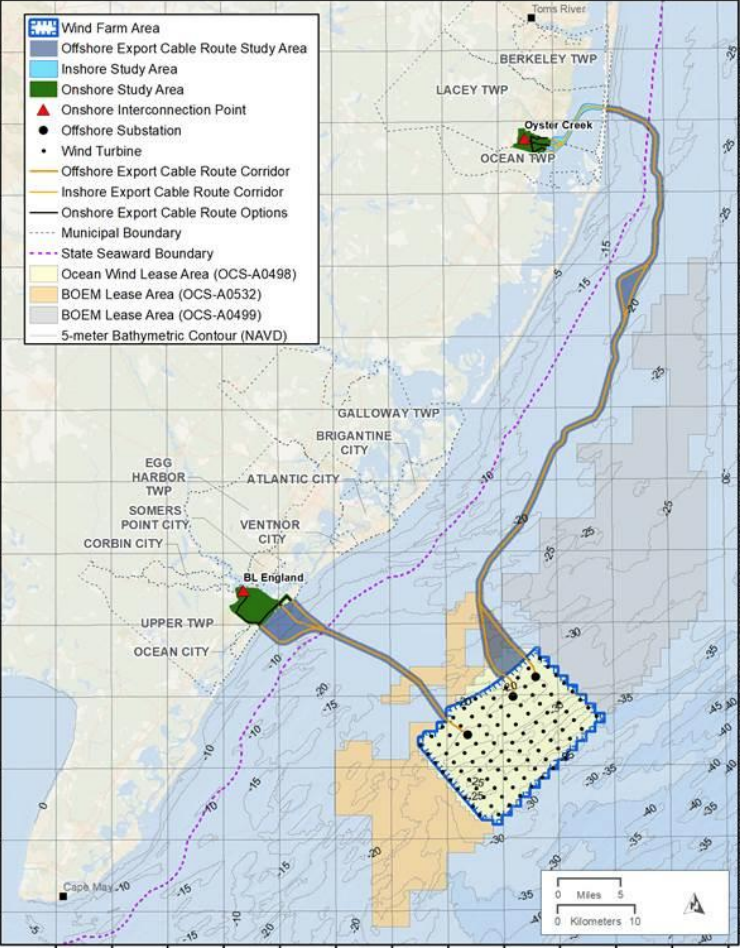

The 1,100-megawatt array would be built between 15 and 27 miles offshore on Ørsted’s federal lease east of Atlantic City, with up to 98 turbines feeding power to three offshore substations.

From there, export cables would carry the energy to a couple of once-thriving power plants on New Jersey bay shores: The disused BL England coal plant, considered by state regulators for conversion to natural gas a few years ago, and the obsolete Oyster Creek nuclear generating station, an industry showpiece when it entered operation in the 1960s. Both sites have grid connections to handle the wind-generated power.

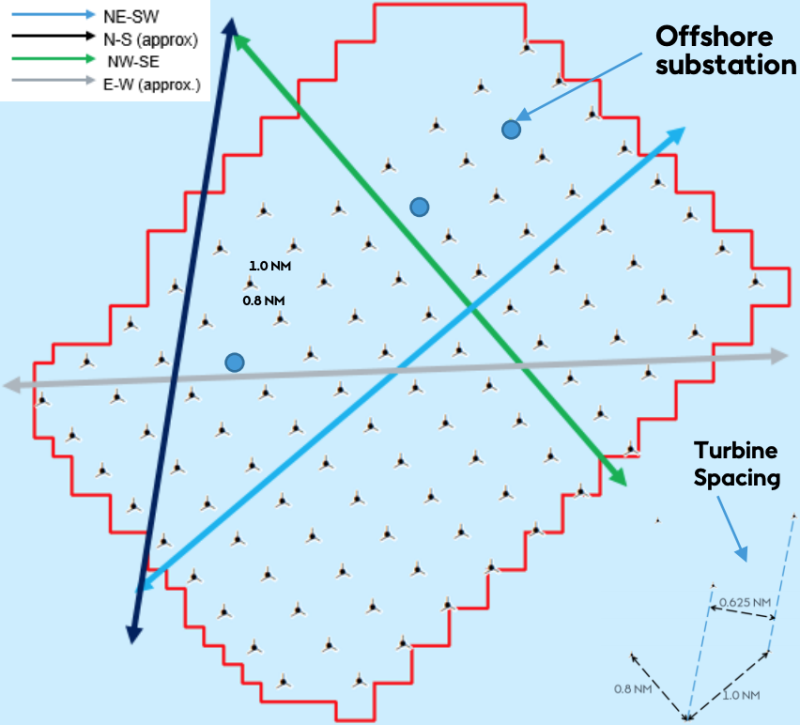

At sea, the Ocean Wind array would be laid out on a grid of 1 by 0.8 nautical mile separation between the turbine towers, an arrangement Ørsted planners say will allow passage for fishing vessels from the ports of Barnegat Light, Atlantic City and Cape May.

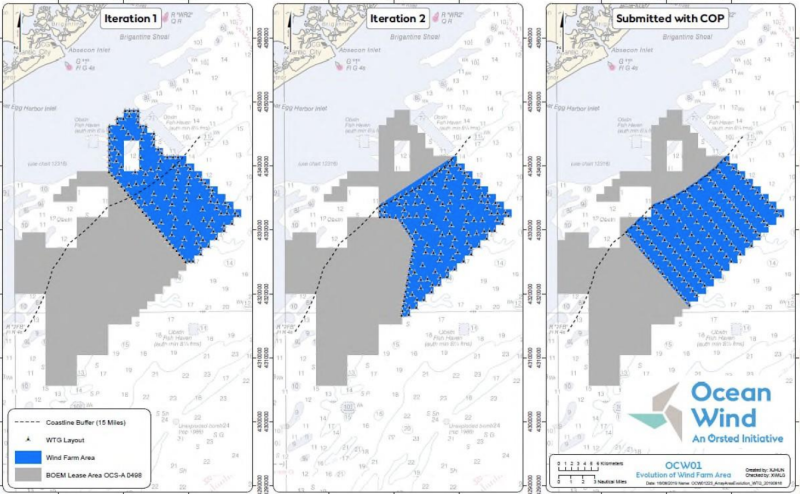

The larger configuration of the array changed over months after stakeholders including fishermen, maritime businesses and the Coast Guard offered their advice, settling on a roughly square grid.

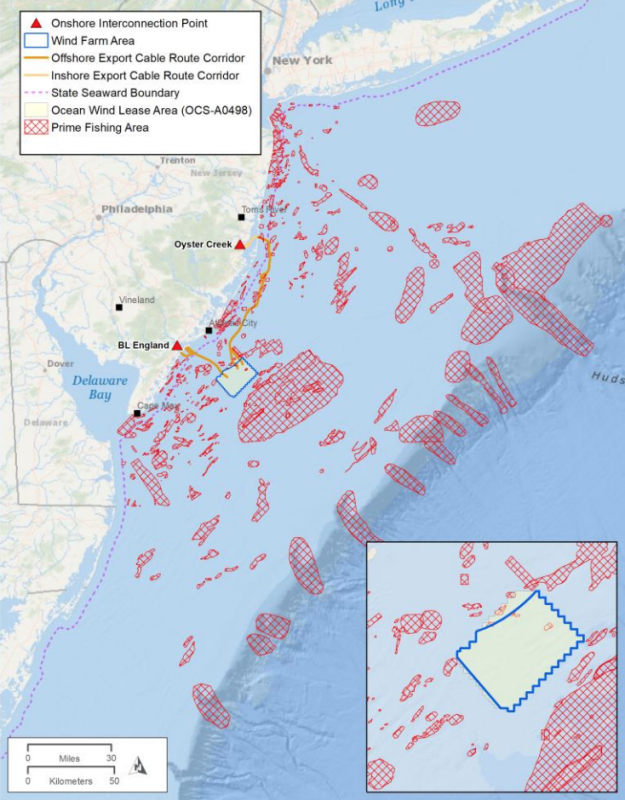

A chart graphic produced by Ørsted portrays the array lying outside larger fishing grounds, as compiled from federal and state data and reports. Consulting the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection’s ecosystem baseline study was a first step for BOEM in examining the feasibility of the Ocean Wind site, said William Waskes, a BOEM project coordinator, during an April 15 online scoping meeting on the plan.

Waskes said the agency considered input from stakeholders including fishermen and the Department of Defense; the Navy, Air Force and Air National Guard use airspace off southern New Jersey for training exercises.

With fisheries, the high-value scallop and surf clam resources were a big concern, and BOEM also adjusted edges of the New Jersey wind energy leases to make space for maritime vessel traffic, he said.

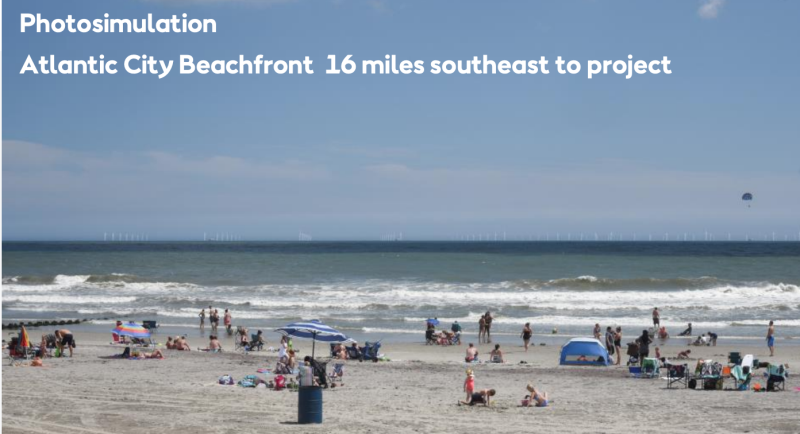

Ørsted also changed its turbine layout design in response to concerns from beachfront communities about the visual impact of turbines, said Pilar Patterson, Ørsted’s project manager for Ocean Wind. Video simulations produced by the company portray turbines closest to shore at 15 miles as blades and nacelles just visible above the horizon, when there is not a layer of marine haze obscuring them.

With both the Biden administration and New Jersey leaders pushing for wind power, some in the beachfront resort towns are not reassured, and restless.

Just south of Atlantic City, Ocean City, N.J., was a hotbed of opposition a few years ago to plans for a natural gas pipeline to repower the nearby BL England plant. Now, there is a faction dead-set against offshore wind energy coming ashore there.

The prospect of Ocean Wind, plus the Atlantic Shores project – a partnership between Shell New Energies US LLC and EDF Renewables North America that wants to build an array, just to the north off Long Beach Island – is hotly debated on that barrier island.

Climate change and sea level rise are serious threats there. But so are changes that offshore wind development might bring for the island’s small but prosperous fishing port at Barnegat Light. Town governments on the island have expressed formal opposition.

“We’re very concerned about the impact on tourism,” said Beach Haven, N.J., Mayor Colleen Lambert during the April 15 meeting on Ocean Wind.

The Ocean Wind tract at its closest is 15 miles offshore and turbine blades could be visible from shore on some days, according to BOEM visual simulations. Lambert noted New York has set an 18-mile minimum in its policy to prevent visual objections.

“It would be nice if the process slowed down,” she added.

In their online presentation, Ørsted planners say the experience of the Block Island Wind Farm – the five-turbine, 30 MW pilot project built off Rhode Island in 2016 – has shown “no loss of property values, tourism revenue, or recreational fishing opportunities.”

Recreational and charter fishing around the turbine structures have made the site an “enhanced fishing destination,” according to the company.

As for Ocean Wind and other projects near the New Jersey coast, BOEM could decide to leave some leased areas undeveloped to mitigate visual or environmental impacts, said Waskes.

Meanwhile, Coast Guard navigation experts are continuing to examine routes for a dedicated tug and tow fairway past the New York Bight wind areas, and NMFS has suggested that BOEM hold meetings with the New Jersey fishing industry to discuss access to its ports like Barnegat Light, Atlantic City and Cape May.

The New England Fishery Management Council, which works closely with scallop fishermen to manage that resource, is “happy to assist BOEM,” said Thomas Nies, the council’s executive director, during the April 15 meeting.

But BOEM also “needs to show that the fishing industry’s needs are being addressed,” Nies stressed. Offshore wind development will bring increasing costs to other maritime users like fishermen and tug and barge operators, and there should be “permit conditions or fee structures that can address these issues,” he said.

Those costs are still unknown, such as how fishermen’s insurance coverage and costs might change, said Jim Kendall, a former New Bedford, Mass., captain and now fisheries consultant. It’s unclear how insurers will view the risk of vessels transiting near turbine arrays, he said.

New York region maritime advocates too have been speaking of safety concerns to BOEM officials.

“Any potential maritime accidents in the New York Bight are unacceptable,” not just from the industry standpoint but for coastal communities that would be affected, said Edward Kelly, executive director of the Maritime Association of New York and New Jersey.