Wind energy projects under construction off southern New England could have effects on the endangered North Atlantic right whale and ocean ecosystem in the Nantucket Shoals region. But it is difficult to determine how those impacts are different from ongoing climate change and other ecosystem trends, according to a report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine.

“The report recommends further study and monitoring of the oceanography and ecology of the Nantucket Shoals region to fully understand the impact of future wind farms,” according to a summary from the NAS.

Right whales have increased their use of Nantucket Shoals waters in recent years, and some scientists have recommended setting buffer areas around wind energy development areas to ensure future turbine operations don’t alter the local ocean ecosystem.

The NAS study was commissioned by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management to address those concerns. The resulting 106-page paper released Oct. 13 concludes that much more detailed study and modeling is required to predict how operating massive wind turbines may change wind and water currents, and food available for whales.

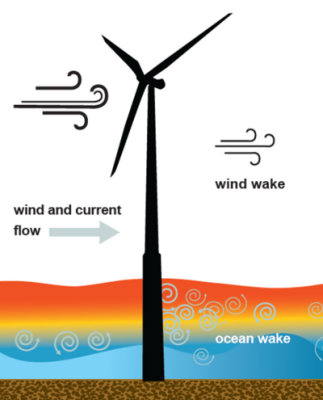

Part of the uncertainty are the effects of “wind wake” trailing behind as wind energy moves through a turbine array, and underwater wake from ocean currents moving past turbine towers on the sea floor.

“The increased turbulence and changing local wind velocity due to spinning turbines both affect the structure and movement of the water, referred to as hydrodynamics,” according to a summary of the National Academies paper.

Those movements of wind and water influence the ocean ecosystem, including production of zooplankton, tiny energy-rich animals that right whales feed on. One species that’s dominant in season off New England is very important to the whales.

“High concentrations of zooplankton, including the primary prey of right whales – the copepod Calanus finmarchicus in winter–spring – may account for the great numbers of right whales observed feeding in the Nantucket Shoals region and other areas of high productivity in Southern New England, for example, Cape Cod Bay,” the paper's authors wrote.

“Successful foraging depends on copepods being found in sufficient densities and at appropriate depths, and as such right whales are sensitive to disturbances of their prey in the water column,” according to the paper. There has not been enough observation and modeling of wind wake effects to predict how wind turbines could change that, the authors say.

Previous European studies and models looked at wind power projects in the North Sea, “which have different hydrodynamic and ecosystem characteristics,” according to the paper.

“Based on what is known, the impacts on ecosystems from development and operation of offshore wind may be difficult to distinguish from natural and other anthropogenic variability (including climate change) in the Nantucket Shoals region, where the oceanography and ecology is dynamic and evolving. Targeted observations and studies are critical to understand and quantify the hydrodynamic and ecological effects of offshore wind in the Nantucket Shoals region.”

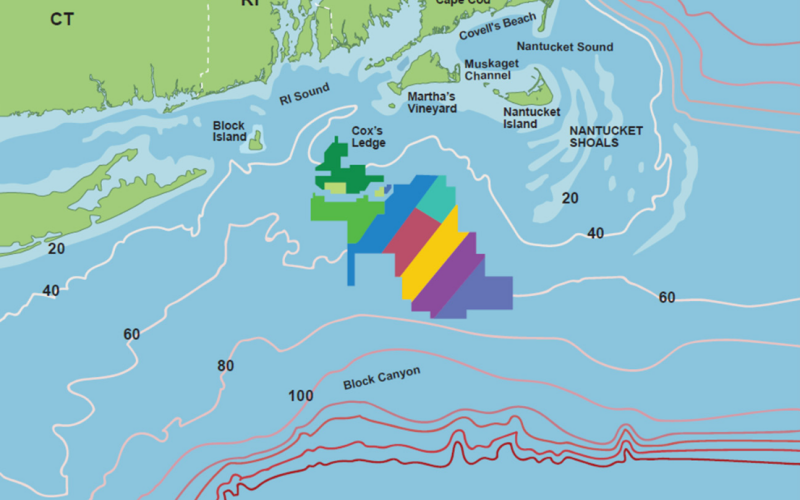

Moreover, the area continues to change even as the first turbines start spinning. Among its lists of recommendations, the academies’ study group says that “studies at Block Island, Dominion, Vineyard Wind I, and South Fork Wind should be considered as case study sites given their varying numbers of turbines, types of foundation, and sizes and spacing of turbines.”

“Major oceanographic changes have occurred in the region since 2000, including warming of surface and bottom temperatures, increased frequency of Gulf Stream warm core rings, and midwater intrusions into the tidally mixed inshore region,” the paper says. “Warming water temperature affects onset, decay, and intensity of seasonal stratification. These changes affect the oceanography of the region, but the long-term trends and consequences remain to be determined, particularly because the system is subject to additional changes. “

None of the European studies have been definitive. But they raised enough questions for whale experts and biologists with the National Marine Fisheries Service to recommend that BOEM take more precautions, including buffer areas between wind energy areas off southern New England and ocean feeding grounds favored by the highly endangered North Atlantic right whale.

Researchers with NMFS, the New England Aquarium and the Cape Cod, Mass.-based Center for Coastal Studies reported in summer 2021 that the right whale population – now estimated at less than 350 animals – have increased their use of waters around Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket in recent years.

In a May 2022 letter obtained by the New Bedford Light through a Freedom of Information Act request, Sean Hayes, chief of protected species at NMFS’ Northeast Fisheries Science Center, told BOEM officials that a conservation buffer of at least 20 kilometers (12.4 miles) from the Nantucket Shoals edge of wind development areas “would reduce the potential for negative consequences to right whale prey and the NARW (North Atlantic right whale) population.

“Concentrating development to the southwest and creating a conservation buffer adjacent to the Shoals is expected to reduce risk by reducing overlap between high species distribution and concentrated areas of construction, operations and maintenance activities, including associated vessel traffic and potential changes in commercial and recreational fishing activity.”

Hayes wrote that right whales need dense concentrations of zooplankton, the tiny animals they feed on, and that “disruptions to prey aggregations in the only known winter foraging area for right whales could have significant energetic and population consequences.”

“Without dense aggregations of prey, right whales will search elsewhere for food, potentially at an energetic loss, given the likely increased metabolic travel costs and that alternative energetically beneficial foraging grounds may not exist during the winter,” Hayes wrote.

Wind turbines “are likely to result in both local and broader oceanographic effects, and may disrupt the dense aggregations and distribution of zooplankton prey through altering the strength of tidal currents and associated fronts, changes in stratification, primary production, the degree of mixing, and stratification in the water column,” Hayes wrote.