Plans for 17 or more offshore wind turbine arrays off the U.S. East Coast mean more imminent peril for the endangered North Atlantic right whale – unless regulators and wind power developers implement sweeping new protection for the animals, according to one expert on the species.

Ship strikes and fishing gear entanglement already top the list of hazards for the right whale population, now estimated at less than 340 animals. Construction work and increasing vessel traffic around wind projects will add to the danger, says Mark Baumgartner, a senior scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute whose laboratory tracks and studies the whales.

“We’ve never found a right whale that died of old age,” said Baumgartner. “We find they die from industrial accidents.”

A presentation by Baumgartner is titled “The Fate of North Atlantic Right Whales in an Increasingly Industrialized Ocean.” In an online discussion hosted Monday by the Rutgers Cooperative Extension Service in New Jersey, Baumgartner gave a blunt assessment of the situation.

“Right now, it’s not good,” he said, “unless we change our industrial practices.”

After centuries of hunting to near-extinction, a modest revival of the population brought the whales’ numbers to 482 in 2010, aided by years with abundant food and successful seasons off the U.S. Southeast where female whales migrate to give birth, said Baumgartner.

But shifting conditions tied to climate change brought more right whales feeding in the Gulf of St. Lawrence – and a series of whale deaths tied to ship strikes and gear entanglements in Canadian waters.

By 2020 the population was estimated at 336, said Baumgartner. At that level, the National Marine Fisheries Service has calculated the average annual death rate in the population must be less than one animal if there is any meaningful chance of recovery.

For an example of the hazards individual whales face, Baumgartner cites the story of a whale researchers dubbed Punctuation, a 40-year-old female that died from a ship strike in the Gulf of St. Lawrence during June 2019.

It was the whale’s second accidental encounter with a ship, on top of five times she was seen entangled in gear, said Baumgartner. Researchers tracking Punctuation’s family history documents her giving birth to eight calves, with three that died; of two documented grand-daughters, one whale was killed and the other entangled.

“How is it possible?” said Baumgartner. “You have to understand the scale of industrial activity offshore.”

Baumgartner said he believes climate change is a greater long-term threat to whale survival. If it's possible to "do wind energy right" that could help to lower atmospherice emissions and slow the changes, he said.

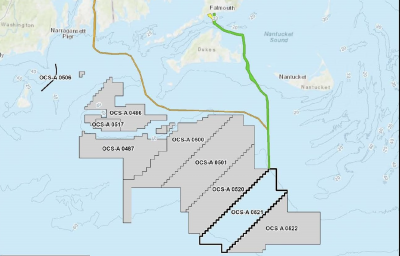

Ambitious wind projects off southern New England and in the New York Bight will up the ante.

Based on studies so far at the Block Island Wind Farm off Rhode Island it appears “the noise just from operation is really minimal,” said Baumgartner. “During construction, there’s a lot of noise.”

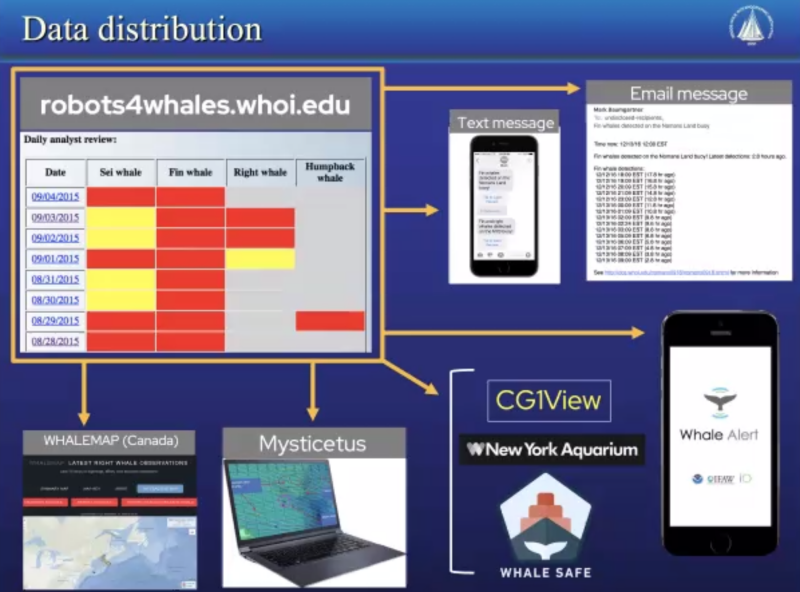

Whales use sound to sense their environment and communicate, so to track them, “we listen for them…whales use it all the time, so we can tell if they’re around,” said Baumgartner, who developed software years ago for monitoring and analyzing those low-frequency sounds in the ocean.

The Low-Frequency Detection and Classification System generates “pitch tracks,” analogous to sheet music, to record the whale sounds. The Woods Hole institute is part of a larger network using digital acoustic receivers, carried on buoys and a fleet of Slocum electric glider robots.

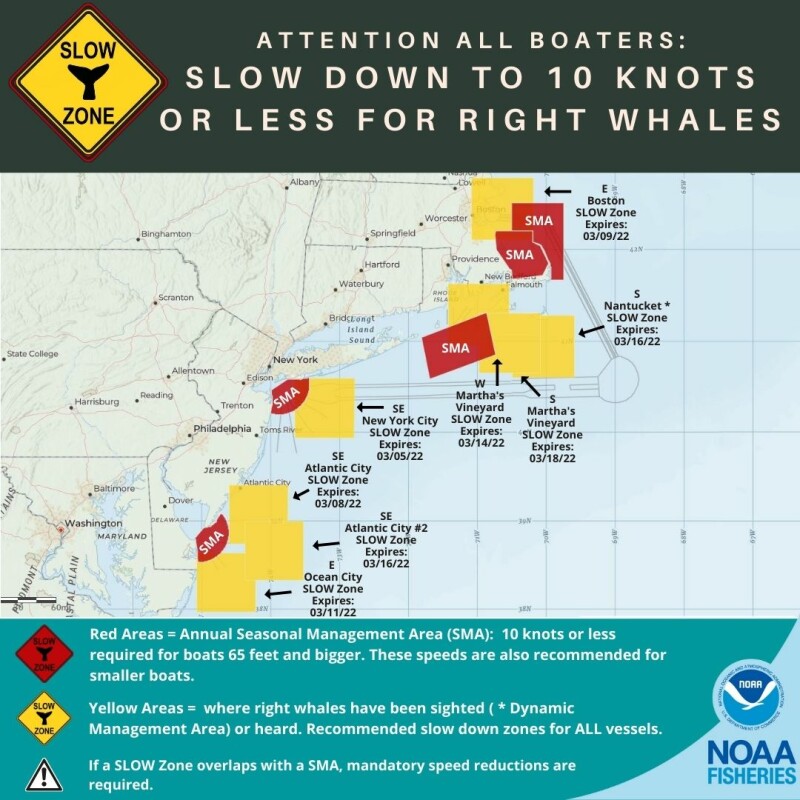

Every two hours, those automated systems beam up their data to an Iridium satellite for relay to the network. Right whale activity sensed by the monitors enable NMFS to trigger voluntary “slow zones” in those areas and around shipping approaches to East Coast ports.

New buoys off Norfolk, Va., and Savannah, Ga., are sponsored by shippers CMA CGM and other partners including wind developers are helping to sponsor gliders, Baumgartner said.

“There’s good research to show the slower ships go, the less lethal ship strikes can be,” said Baumgartner. Slow zones are voluntary in the U.S., and could be “a playing field that’s not necessarily level” if some ship operators choose to exceed the 10-knot limit to gain commercial advantage, he noted.

For wind turbine construction, acoustic monitoring will be able to alert for the presence of whales. That can be used to schedule vessel activity and construction, including extremely stressful noise like pile driving, when whales are not around, said Baumgartner.

More can be done to protect whales and still use the ocean, Baumgartner stressed.

“It’s not that we’re talking about not having shipping, fishing or wind energy,” said Baumgartner. But “if we don’t change how we do things…we’re going to lose this species.”