Atmospheric wakes trailing behind offshore wind turbines will change oceanographic and marine ecosystem conditions in the North Sea as more and larger turbines are built there to meet Europe’s energy needs, according to a recent study published in the journal Nature.

The paper by researchers Ute Daewel, Naveed Akhtar, Nils Christiansen and Corinna Schrum of the Institute for Coastal Systems in Germany used numerical modeling to show how wind wakes may change local conditions.

Those systems could be moved by plus or minus 10 percent, not just within turbine arrays but over a wider region, the team wrote. That includes “primary production:” the generation of nutrients at the base of the marine food chain.

The Nov. 24 publication of their paper, “Offshore wind farms are projected to impact primary production and bottom water deoxygenation in the North Sea,” is the latest from scientists investigating how larger-scale offshore wind projects may alter ocean conditions and ecosystems.

As in Europe, U.S. researchers too are looking at how wind wake and ocean currents flowing for miles behind turbines will change the seasonal stratification of cooler water close to the bottom, peaking in summer and turning over in fall and spring.

None of those studies are definitive, but they are raising enough questions for whale experts and biologists with the National Marine Fisheries Service to recommend that the Bureau of Offshore Energy Management take more precautions, including buffer areas between wind energy areas off southern New England and ocean feeding grounds favored by the highly endangered North Atlantic right whale.

Researchers with NMFS, the New England Aquarium and the Cape Cod-based Center for Coastal Studies reported in summer 2021 that the right whale population – now estimated at less than 350 animals – have increased their use of waters around Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket in recent years.

In a May 2022 letter, obtained by the New Bedford Light through a Freedom of Information Act request, Sean Hayes, chief of protected species at NMFS’ Northeast Fisheries Science Center, told BOEM officials that a conservation buffer of at least 20 kilometers (12.4 miles) from the Nantucket Shoals edge of wind development areas “would reduce the potential for negative consequences to right whale prey and the NARW (North Atlantic right whale) population.

“Concentrating development to the southwest and creating a conservation buffer adjacent to the Shoals is expected to reduce risk by reducing overlap between high species distribution and concentrated areas of construction, operations and maintenance activities, including associated vessel traffic and potential changes in commercial and recreational fishing activity.”

Hayes wrote that right whales need dense concentrations of zooplankton, the tiny animals they feed on, and that “disruptions to prey aggregations in the only known winter foraging area for right whales could have significant energetic and population consequences.”

“Without dense aggregations of prey, right whales will search elsewhere for food, potentially at an energetic loss, given the likely increased metabolic travel costs and that alternative energetically beneficial foraging grounds may not exist during the winter,” Hayes wrote.

Wind turbines “are likely to result in both local and broader oceanographic effects, and may disrupt the dense aggregations and distribution of zooplankton prey through altering the strength of tidal currents and associated fronts, changes in stratification, primary production, the degree of mixing, and stratification in the water column,” Hayes wrote.

In the North Sea paper, researchers say their modeling studies show that expanding offshore wind installations there “will substantially impact and restructure the marine ecosystem of the southern and central North Sea. Changing atmospheric conditions will propagate through ocean hydrodynamics and change stratification intensity and pattern, slow down circulation and systematically decrease bottom shear stress.”

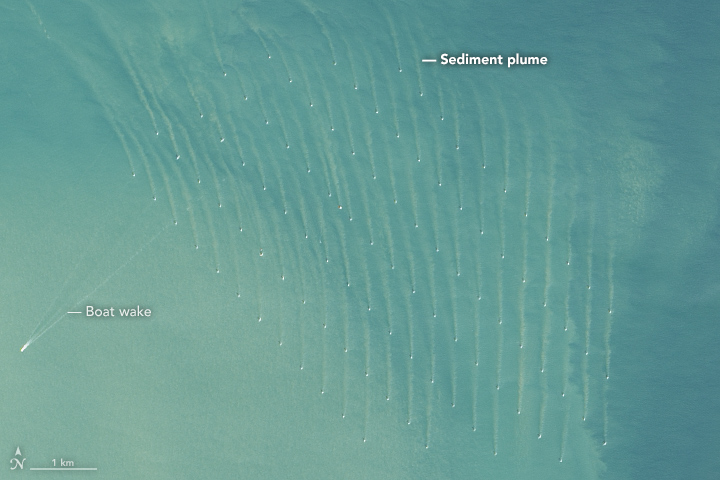

Wake effects streaming from the leeward side of turbine arrays can extend 40 miles or more, “depending on atmospheric stability, with a wind speed reduction of up to 43 percent inside the wakes leading to upwelling and downwelling dipoles in the ocean beneath,” the authors wrote. That changes mixing, stratification, temperature, and salinity in the waters below.

Future North Sea offshore wind projects “are planned in exactly those highly productive areas, which are known to be ecologically highly important. Our model results show that the systematic modifications of stratification and currents alter the spatial pattern of ecosystem productivity,” the authors wrote.

The potential atmospheric effects of next-generation offshore wind projects have been underrated, the North Sea researchers say. Looking ahead to wind developers’ plans, the researchers say “the marine ecosystem responds very clearly to the changes in the atmosphere leading to changes in ocean stratification, advective processes and a systematic decrease in bottom shear stress.”

Those changes will show up in “higher trophic levels of the marine ecosystem” through the ocean food chain, they noted.

On the U.S East Coast, similar modeling studies predict changes in how zooplankton will change in distribution as offshore wind projects are built.

Those studies suggest “similar impacts could occur with right whale’s zooplankton prey,” Hayes of NMFS wrote in his letter to U.S. offshore energy planners. “The scale of impacts is difficult to predict and may vary from hundreds of meters for local individual turbine impacts, to large-scale dipoles of surface elevation changes stretching hundreds of kilometers.”