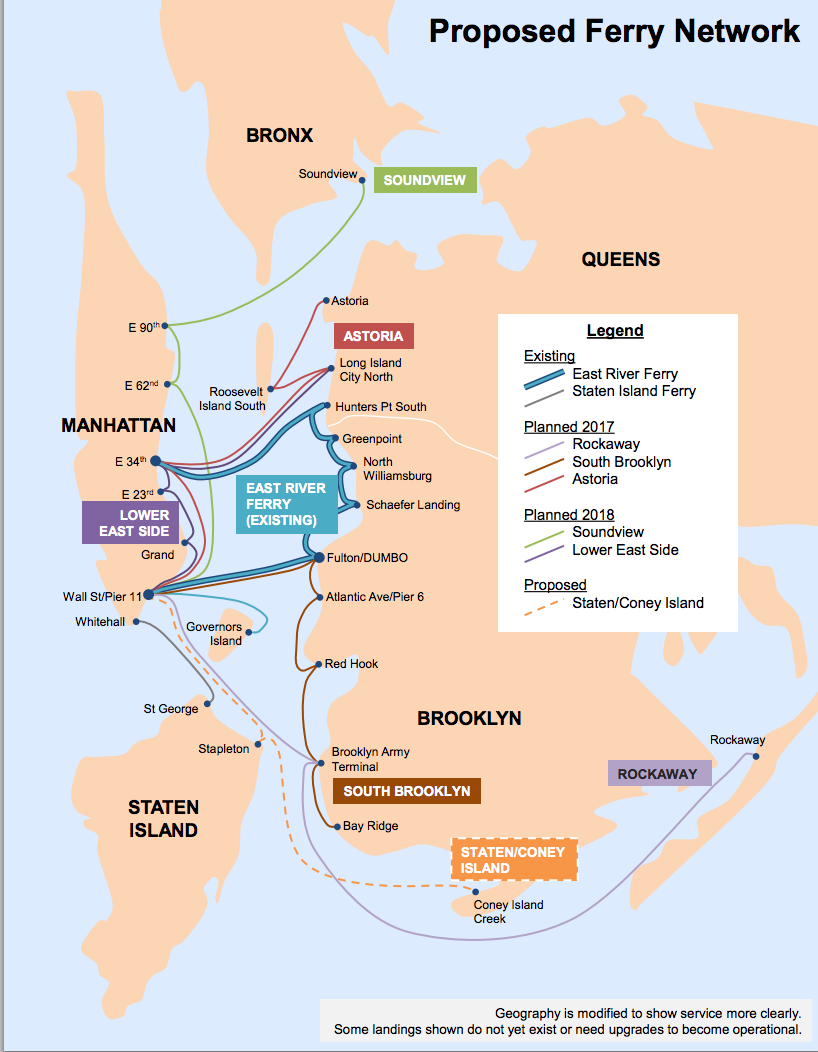

New York’s budding Citywide Ferry is a hugely ambitious plan to build and deploy a complete public transit system on the water by summer 2017.

For the administration of Mayor Bill de Blasio, it is a showpiece project to extend waterborne transportation – for many years a province of more well-paid Wall Street commuters – to average New Yorkers living in the boroughs.

Some 550,000 people live within half a mile of the new ferry landings, some in view of the water. For $2.75 – the cost of a subway fare – they could travel by water, and gain irreplaceable time back in their lives now lost on arduous bus and rail commutes.

In the months since city officials announced their choice of San Francisco-based Hornblower Cruises & Events to develop and run the system, much attention has focused on how the ferries will be built that fast. But to make this work in the long run, the city and the Hornblower operator, HNY Ferry Fleet LLC, will need to capture and hold those 4.6 million riders a year that ferry advocates foresee.

Fuel prices are at historic lows now, and the city’s economy on the upswing. Can future administrations maintain the resolve to keep those fare subsidies and other support up when times get tough?

The nonprofit CityLimits.org has published an extended analysis that is well worth reading, for its questions of price points and particularly long routes – like a ferry swing out the lower harbor to Rockaway, the city’s eastern frontier.

For a report about the ferry sector for WorkBoat’s upcoming October issue, I called one of the experts. Inna Guzenfeld, a Brooklyn Heights native, graduate of New York’s famed Pratt Institute, and independent planner and waterfront expert, wants to see the ferries succeed.

But she is clear-eyed about the prospects.

“How do we deal with fuel spikes, potentially unready markets?” asked Guzenfeld, who is concerned about the system winning and holding ridership in its rapid deployment.

Compared to a 10-minute ride on the East River, Rockaway is another undertaking entirely. Community leaders there have begged for ferry service as an alternative to their constituents’ long workday schleps by rail to Manhattan, but earlier trial proved uneconomical.

If Citywide Ferry wants riders to commit, it must perform on time. “If you can’t maintain peak headways to the Rockaways, you have to have another boat” that might add $500,000 to operating costs for the route, Guzenfeld said.

That would mean a bigger subsidy – and more long-term commitment from the city.

“We’ve come to think of water-based and land-based transportation separately,” compared to earlier eras in the city when trolleys ran to ferry landings, Guzenfeld said. Integration of ferries with the rest of mass transit – like swiping a MetroCard commuter pass to get on a boat, like you would the subway – may one more way to keep and hold a whole new generation of ferry riders.