Workboat roles are expanding along with the ships they service

Three miles long and 1,000' wide at its narrowest point, the Kill Van Kull channel between Staten Island, N.Y., and Bayonne, N.J., is a keyhole approach for containerships, routinely navigated with local pilots in and out of the bustling terminals at Port Newark and Port Elizabeth.

It is a spectacle for ship spotters and photographers, who watch some of the biggest vessels in the world and their tugboat escorts pass smoothly.

Thirty years ago, planners at the Port of New York and New Jersey knew the squeeze would get even tighter, with the shipping industry’s relentless drive toward bigger and more efficient ships.

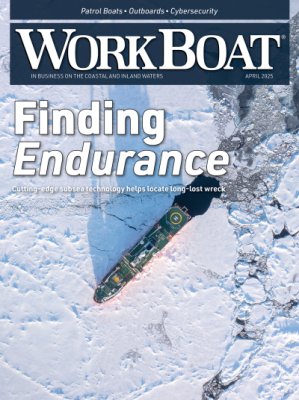

The containership MOL Benefactor was the first post-Panamax ship to transit the widened Panama Canal and call at New York, Savannah, Ga., and Norfolk, Va. Georgia Port Authority/ Stephen B. Morton photo.

At the west end of the Kill Van Kull, one more step in the port’s adaptation is taking shape: a $1.3 billion rebuilding of the Bayonne Bridge to raise its vertical clearance to 215' from 151', to accommodate the air draft of new ships being built to reach the U.S. East Coast through the widened Panama Canal.

After delays, the bridge is now expected to be ready by the end of 2017.

“With these new ships, you’re going to have air draft of 175' to 195' … ships that are around 1,200' long and 160' wide,” said Ed Kelly, executive director of the Maritime Association of the Port of NY/NJ.

For the workboat sector, that brings big challenges, and big opportunity. Pilots have been training to handle the new ships, in simulators at the Maritime Institute of Technology & Graduate Studies, Linthicum Heights, Md., and in person with pilots at West Coast ports. Naval architects and tugboat builders are pushing design parameters to get even more horsepower into tugs to handle bigger customers.

The leap forward in gross tonnage and adjusting for wind effects is a challenge for harbor mariners, said Capt. Jon Miller, vice president of the Metro Pilots Association in New York Harbor.

“The biggest thing is the tonnage. The wind is significantly more. We thought that the tonnage would counter that. But they do react,” Miller said. An upper wind limit of 35 knots for docking ships will likely be reduced to 30 knots for the biggest post-Panamax vessels, with other rules being developed by the harbor deep draft advisory committee, he said.

“There’s going to be a need for bigger boats, when you think of the windage on the sides of these ships,” Kelly said. “The number of tugs per vessel and the power of tugs will have to be increased.”

Ships too big for the old Panama Canal have been coming to the U.S. West Coast, and some to the East Coast via Egypt’s Suez Canal. But the canal widening is a game changer because it enables a shorter route and new efficiencies in moving cargo to U.S. consumers, Kelly said. It means goods can go from Atlantic ports by rail or truck into the populous U.S. heartland, instead of by long overland haul from California.

East Coast ports are in different stages of adapting, said professor Anthony Pagano, director of the Center for Supply Chain Management and Logistics at the University of Illinois Chicago.

“Most of them are not really ready yet. They are working on it, and a lot of them have a long way to go,” said Pagano, who in 2012 co-authored a study of U.S. ports’ preparations with Grace Wang of Texas A&M University at Galveston.

DEEPER CHANNELS NEEDED

Baltimore was prepared early, with a 50' channel since 1990 and 50' draft containership berth at its Seagirt terminal completed in 2012, as was Norfolk, Va. This summer the Corps of Engineers and Port Authority of New York & New Jersey finally completed the port’s main navigation channel deepening program, a 25-year, $2.1 billion project conceived in the 1980s to assure the New York region’s continued dominance.

“Baltimore’s been a great story. We had the channel and the berth ready. They were there to meet the challenge,” said Mike Reagoso, vice president of Mid-Atlantic operations for McAllister Towing and Transportation Co. Inc., in Baltimore.

CMA CGM and Evergreen Line are major players in Baltimore, so tug crews and state docking pilots have more experience than most moving containerships in the 1,100' to 1,200' range. The nearby MITAGS training and ship simulator in Linthicum Heights, Md., is a major asset. “We have tug captains and mates in the simulator too” to get a feel for the ships, Reagoso said.

At such sizes, ships can have seven-knot minimums to keep steerage, “so we have to slow them down coming in,” Reagoso said. An 1,100' ship escort is typically made up of three tugs with 5,000 or 5,100 hp each. McAllister’s new tugs are being built with 6,700 hp. “Everyone’s building bigger equipment that I know of on the East Coast.”

Between 1989 and 2016, some 38 miles of federal navigation channels in New York Harbor were deepened. Planning for channel depths went deeper, from 40' to 45' to 50'. Bedrock was blasted at the bottom of the Kill Van Hull. The newly shattered boulders of diabase — the same stuff in the Palisades cliffs along the Hudson River — was barged out of the harbor and dropped in the ocean to create artificial fishing reefs.

“This harbor deepening may be the most important and influential project related to modern day economics in the Northeast,” said Col. David Caldwell, commander of the Corps’ New York District, during a Sept. 1 event to mark the completion of dredging. “The harbor deepening was accomplished safely even while the port remained open throughout all phases of construction, whether dredging or blasting.”

The containership MSC Jeanne inbound at Charleston harbor in September. Kirk Moore photo.

In some ways Charleston, S.C., has been well ahead of the curve. The city’s iconic Arthur Ravenel Jr. Bridge, completed in 2005, has 187' of vertical clearance for vessels heading to port terminals on the Cooper and Wando rivers. Its diamond-shaped suspension towers are protected by stone revetments designed to withstand an allision from a container ship at 12 knots.

What remains is funding for deepening the harbor entrance to 54' and federal channels to 52' – a $509 million project recommended for funding by the Corps in January. The funding was held up recently as Congress fought over the Water Resources Development Act. After some tense days, Charleston was included in a House version of the bill Sept. 28. Jim Newsome, president and CEO of the South Carolina Ports Authority, said after the vote that Charleston was “well-positioned to be the deepest harbor on the East Coast by the end of the decade.”

Post-Panamax size ships have been calling at Charleston for years, and in July the number was up to around 16 vessels out of the 26 making regular calls, according to Newsome. Thanks to its tidal ranges of around 5', the port routinely gets ships 1,100' in length drawing 48', and deepened channels will allow them to pass under the Ravenel bridge at any time.

“We’ve seen a steady trend of post-Panamax over several years,” said Capt. John E. Cameron, executive director of the Charleston Branch Pilots Association. “The trend toward upsizing ships has been pretty steady.”

There are 20 Charleston pilots and four boats, including the Fort Ripley, an aluminum 64'x21’x10'6" emergency response boat built by Gladding-Hearn Shipbuilding that was among WorkBoat’s Significant Boats of 2014.

“We’re traveling farther offshore and burning more fuel” to service the bigger ships, Cameron said. With its deep water, Charleston is also a good final port for ships to take on cargo – including BMW automobiles, assembled at the company’s Spartanburg, S.C., plant and lined up at the Columbus Street terminal, now the ro/ro connection for BMW’s imports and exports.

NEXT STEPS

The containership Hanover Bridge approaches the Arthur Ravenel Jr. Bridge in Charleston, S.C., after transiting the widened Panama Canal. Kirk Moore photo.

The Panama Canal brought a series of first-time events to East Coast ports. In Charleston, the first arrival through the widened canal was the 1,102'x151' Hannover Bridge, an 8,200-TEU ship from China, on July 14. The first 14,000-TEU vessel may call at Charleston sometime in early 2017, said Erin Dhand, a spokeswoman for the South Carolina Ports Authority.

The 1,105’x 157' MOL Benefactor, a 10,000-TEU ship delivered in March, transited the new Panama Canal and showed up in New York Harbor on July 7 at the Global Container Terminal in Bayonne, N.J. It set a record as the largest cargo ship to call at the port. A week later the containership arrived at the Port of Savannah, Ga., Charleston’s competitor in the Southeast market, which is in the midst of its own program to deepen channels to 49'.

“To be a major container operator, you need to have at least weekly service,” said Kelly of the Maritime Association of the Port of NY/NJ. “I would suspect the proper size will probably be in the 12,000- to 14,000-TEU range. One guy buys a bigger ship and that gives him a 20% to 30% advantage over his competitors. You pay the same for fuel, you pay the same for pilots, the same for tugs.”

One expectation might be that those bigger ships and more efficiency may actually reduce work for the tugs and others that serve them. But this is not clear.

“It’s a difficult prognosis for what it means for pilotage,” said Cameron of the Charleston pilots. “The mathematics of it would indicate the number of ship calls will be fewer.”

Then there is the ongoing turmoil in the shipping industry, with the Hanjin Shipping Co. bankruptcy and predictions of further consolidation in the container trade. But overall maritime trade continues a slow upward trend.

In recent years cargo statistics have not been very impressive, Pagano of the University of Illinois said. But he thinks those numbers will take a bigger turn in the coming years. “There’s been a downturn in shipments from Asia because of the slow growth of the economy,” Pagano said. “I don’t think you can look at this and predict that’s indicative of what we will see in the future. Not only is it going to lower the cost of shipping from Asia to the U.S., but in the other direction.”

The widened canal will take a lot of U.S.-produced liquefied natural gas toEast Asia markets, particularly Japan, where energy companies are looking to secure reliable and diverse energy sources.

There are positive signs in the port of New York and New Jersey, which saw average yearly cargo growth of 4% since 2000. There was a big 10.4% jump in cargo volumes in 2015.

“What’s happened is that trade has continued to grow. This is not a new phenomenon,” said Kelly, who has witnessed the port’s earlier evolutions to bigger ships for decades. “The volume will continue to increase.”

“From our perspective, we’re doing what we can to prepare,” said Miller of Metro Pilots. “When I started as a pilot seven years ago, they were all talking about 965' [ships], that was the big thing. Now, it’s like nothing.”