The wreck of a Coast Guard cutter that played a key role in a major Pacific battle of the Spanish-American War has been positively identified off Point Conception on the southern California coast, officials with the Coast Guard and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said Tuesday.

The McCulloch helm. NOAA/USCG/VideoRay photo.

The 219’x33.4’ revenue cutter McCulloch was found and surveyed by a joint Coast Guard-NOAA team in October 2016, using the Shearwater, NOAA’s research vessel for the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary. Seven dives using the VideoRay Mission Specialist ROV deployed from the Shearwater yielded images confirming the wreck’s identity.

The first clue was a 15” torpedo tube, molded into the cutter’s bow stem — a distinctive naval weapon of the late 1890s, along with four “six-pounder” rapid-fire guns of 3” bore that fired the first shots at Spanish shore batteries in the Philippines during the 1898 Battle of Manila Bay.

The biggest vessel in the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service when it was commissioned in 1897, the McCulloch drew the first enemy fire — and suffered the only American crewman to die during the Battle of Manila Bay in the Spanish-American War.

Approaching the Spanish positions in early morning darkness of April 30, 1898, a sudden fire of coal soot in the McCulloch’s stack attracted the Spanish gunners’ attention. Chief Engineer Frank Randall was fighting the fire when he succumbed to heat and exhaustion, according to a NOAA history of the ship.

Led by Adm. Thomas E. Dewey on the cruiser Olympia, the U.S. squadron destroyed the Spanish fleet, where 381 sailors died in the one-sided outcome. That victory confirmed the U.S. as a major power in the Pacific — Dewey dispatched the McCulloch, his fastest vessel, to Hong Kong to spread the news. The McCulloch then returned stateside, to a career patrolling the eastern side of that sea frontier from its base at San Francisco.

The cutter ranged from the Mexico border up to Cape Blanco in Oregon. She later became part of the Bering Sea Patrol, enforcing fur seal regulations around the Pribilof Islands, and serving as a floating courtroom for federal authority in the Alaska territory.

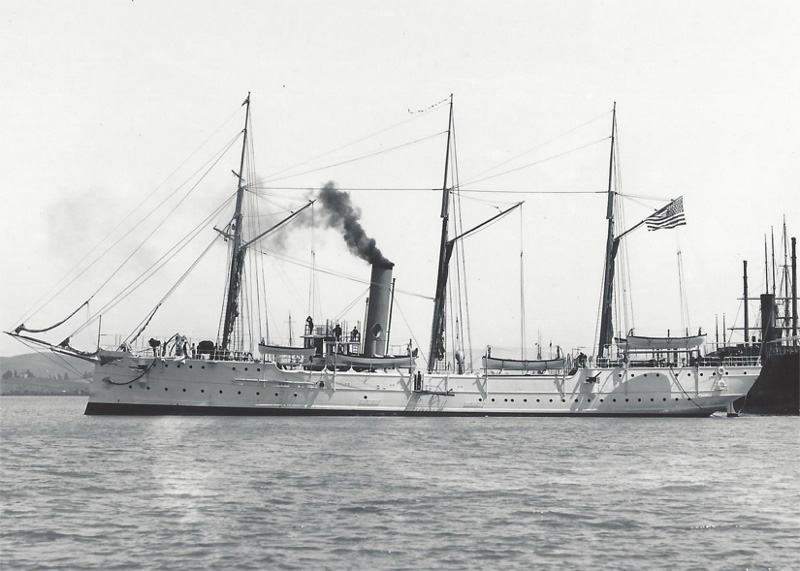

Built at a cost of $200,000 by William Cramp and Sons, Philadelphia, Pa., in 1896, the McCulloch was rated for ice, with a hull built using wood planks over steel framing. With a single triple-expansion marine steam engine, the McCulloch had a cruising speed of 17 knots — and was still rigged for sail for extended range, as a barkentine with three masts.

Returning to San Francisco in 1912, the McCulloch went into the Navy yard at Mare Island in 1914 for a major overhaul and repower, converting to the dual-fuel of that transitional era — boilers that could run on both coal and oil — and to have its mainmast removed and bowsprit shortened.

The McCulloch sinking in 1917. San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park photo.

That next phase of its career in the newly formed Coast Guard (The Treasury Department's Revenue Service was merged with the U.S. Lifesaving Service in 1915 to form the Coast Guard) was short-lived. On June 13, 1917, the cutter was proceeding cautiously in dense fog, returning from San Pedro, Calif., to San Francisco and four miles west-northwest of Point Conception, when Capt. John C. Cantwell and Ensign William Mayne heard a steamer’s fog signal off the starboard bow, according to a NOAA history.

“Nearby, the passenger steamship Governor was southbound from San Francisco to San Pedro. Captain Howard C. Thomas, master of the Governor, heard McCulloch’s fog signal and gave the order 'full speed astern' and to blow three whistles to indicate the vessel’s movement full speed astern," Cantwell recounted. "McCulloch was off the Governor’s port bow when the two ships collided, striking the McCulloch’s starboard side forward of the pilot house, holing the cutter. All of McCulloch’s crew were taken safely aboard Governor before the cutter sank to the sea floor 35 minutes later.”

Cantwell later described the evacuation:

“When the boats were clear of the ship, Chief Engineer Glover in charge of the gig, came alongside and advise me to leave the ship as she was sinking faster every minute and nothing more could be done to save her. I thereupon slided down the boat-falls into the gig and we pulled clear to await further developments. The entire forward section of the deck was submerged and the propeller was half out water. At 8:06 A.M., about twenty minutes after the collision, the McCulloch with colors flying, suddenly up-ended and sank in 60 fathoms of water”

John Arvid Johansson, the McCulloch’s acting water tender, had been in his bunk and was severely injured. Robert Grassow, the ship’s carpenter, rescued him:

“I heard the signal to abandon ship and went up on deck through the companionway onto the main deck to go to my station when I heard someone singing out for help. It was Johansson and he was all doubled up in the wreckage about three feet from where his bunk was. He was out against the ice boxes. There was nobody else around, so I took some of the wreckage away and there was a piece of wood eight inches long stuck in his side. The master-at-arms passed the word for men to carry him to a surf boat.”

Johansson died three days later in a San Pedro hospital. All the crew were taken aboard the Governor, where none of the 429 passengers and crew had been injured. The steamship was found to be at fault in the collision and its operators settled with the government in 1923 for $167,500.

An undated photo of the McCulloch crew courtesy of the U.S. Coast Guard Historian's Office.

Coast Guard and NOAA officials held a media event Tuesday at the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park to announce the discovery of the wreck, and pay tribute to the cutter and crew.

“McCulloch and her crew were fine examples of the Coast Guard’s long-standing multi-mission success from a pivotal naval battle with Commodore Dewey, to safety patrols off the coast of California, to protecting fur seals in the Pribilof Islands in Alaska,” said Rear Admiral Todd Sokalzuk, commander of the 11th Coast Guard District, in a statement marking the discovery. “The men and women who crew our newest cutters are inspired by the exploits of great ships and courageous crews like the McCulloch.”