Offshore wind energy developers are moving to set up their first U.S. manufacturing and support bases, sensing momentum in the market with New York and New Jersey seeking a combined 12 gigawatts of new energy by 2030.

A daylong conference at the State University of New York Maritime College on Thursday brought together wind companies, state officials and the maritime industry to talk about the industry’s coming workforce needs and potential for job growth.

The world’s biggest wind company, Denmark-based Ørsted, has an agreement with a German steelmaker to set up a manufacturing hub in southern New Jersey to finish turbine foundations for its Ocean Wind project off Atlantic City, said Fred Zalcman, who heads market development for its U.S. division.

Another winner could be upstate New York, where Ørsted and Equinor are looking to the Hudson River ports of Coeymans and Albany as bases for manufacturing, floating massive turbine components downriver for eventual transport to assembly at sea on the companies’ federal energy leases.

The Ocean Wind project could be the world’s largest at 1,100 megawatts, powered by 853’ high Halide 12 MW turbines, in a deal recently signed between Ørsted and manufacturer GE.

“When we look globally, the U.S. market really bubbled to the top,” with its attractions of high power demand, a shallow continental shelf for building turbines, and a favorable political climate in Northeast states, Zalcman said.

“So we’re right in the crux of this market,” he added.

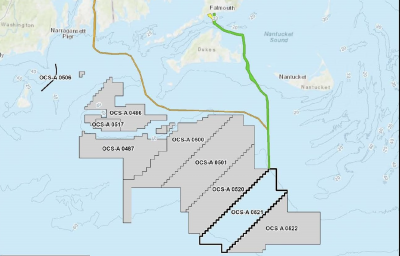

So too is the U.S. commercial fishing industry, where concerns about the impact of building turbines off Massachusetts this summer prompted the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management to hold off issuing an environmental impact statement for the Vineyard Wind project.

Zalcman and other wind company representatives said they see BOEM is still working on individual wind project applications, even as the agency takes a broader assessment of the potential cumulative impacts of turbines strung off the Eastern seaboard.

The wind companies are working with one fishing industry coalition, the Responsible Offshore Development Association, to resolve questions of user conflicts and the science of environmental and fisheries impacts, said Doug Copeland, development manager for Atlantic Shores Offshore Wind, a joint venture of EDF Renewables North America and Shell New Energies to build a wind turbine array in Mid-Atlantic waters.

At this point talking to fishermen is his foremost issue, said Copeland, who’s been involved in talks specifically with surf clam operators.

“They say, ‘We’re more than stakeholders, we’ve been here for hundreds of years.’ We really have to take that to heart,” said Copeland. “They’re the users of this resource.”

Wind power advocates tout the potential of the new industry to revitalize the industrial waterfront of New York City, where city officials and Red Hook Marine Terminals in Brooklyn are marketing acreage for turbine assembly and staging for construction.

New York state entered into power agreements with offshore wind developers Equinor and Ørsted for a combined 1.7 gigawatts of power by 2024. NYSERDA image

But there’s acute awareness of how all that would co-exist with others in the bustling port of New York Bight shipping lanes and fishing grounds.

“We’re right in between two of the busiest shipping lanes in the country,” said Julia Bovey, director of external affairs for Equinor Wind USA and its Empire Wind project off New York Harbor.

She contends “it’s not a terrible idea” because it makes sense to locate turbines near the urban load center of New York, and can be done safely: “It’s more difficult to build in deeper waters, with longer cable runs.”

Maritime labor unions and institutions are looking to new training programs for an offshore wind energy workforce. Unlike Europe, there are yet no U.S. standards and certifications for working in the industry, said professor Shmuel Yahalom, director of the Offshore Renewable Energy Center at SUNY Maritime.

The college is assembling curricula to train future mariners to work in wind energy, and may have these first elements in place next year. Meanwhile there’s a need for studies into a host of pressing issues, such as safe operating clearances for vessels transiting past the towers in turbine arrays, Yahalom said.

“Is it 2 miles? Three miles? Does anyone know?” he said.

The Coast Guard is working on those questions, with its own coast wide study of potential vessel traffic impacts and needs for safe transit lanes. Coast Guard officials have said some findings may come later this year.

“So it’s absolutely critical we have well functioning shipping lanes in and out,” said Capt. Jason Tama, commander of Coast Guard Sector New York. Other concerns are security issues raised by a new offshore energy industry, and how to safely conduct search and rescue missions near massive turbines, he said.

“So there’s a thousand issues we have to work through,” Tama said.