Offshore wind energy developers are courting recreational fishermen in the New York Bight, who could gain dozens of new fishing spots around turbine towers, but worry about impacts of the massive projects on traditional fishing grounds.

“Obviously the hot button for us is access,” said charter captain Paul Eidman of Anglers for Offshore Wind Power, a project of the National Wildlife Federation, which hosted the meeting in Toms River, N.J., on Wednesday along with the American Littoral Society for offshore wind companies and recreational fishermen.

“There’s a lot being proposed to go out in the ocean and on the bottom,” said Tim Dillingham of the littoral society, adding that the developing industry must avoid critical fish habitat and seafloor bumps and ridges that are important to anglers and the region’s big charter and party boat fleet.

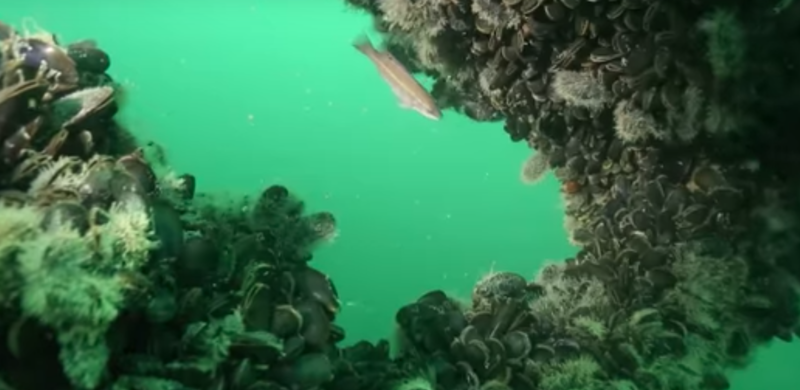

There are conflicted feelings in the recreational community. Many anglers want to see the new hard structure that turbine construction would put into the water, swiftly attracting hydroid and shellfish growth that become the base for new fishing hotspots, much like artificial reefs.

The American Wind Energy Association makes that a big selling point, advertising the success anglers and charter captains have with fishing for summer flounder, black sea bass and cod around the Block Island Wind Farm, the nation’s first commercial offshore installation built off Rhode Island in 2016.

An angler with a black sea bass caught near the Block Island Wind Farm in Rhode Island. Anglers for Offshore Wind Power photo

“Once the mussels take hold, it goes right up the food chain,” said Eidman, who has fished the Block Island array and speaks glowingly of “a great day fishing, sea bass, lots of doubleheaders.”

“I think we have a fantastic opportunity here,” he told the group.

Some were skeptical.

“You’re talking about a forest of these” turbines, said Robert Rush Jr. of United Boatmen, a charter captains’ trade group, and a member of the New Jersey Marine Fisheries Council, referring to the state’s goal of 1,100 megawatts of offshore power by 2030.

“We haven’t seen the science yet” for potential effects on the region’s fish populations, said Rush. “If you can’t show the science we’re not on board.”

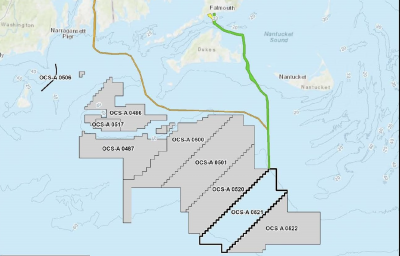

Many wanted more assurance of continued access in and around the turbine arrays. The federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management and Coast Guard have publicly insisted they will not allow navigation to be curtailed except for safety purposes during construction. But there could be some safety zones near transmission substations along the power cables to shore.

“The concern is that could be changed after the towers go up, “said John Toth of the Jersey Coast Anglers Association.

“Another federal agency or Homeland Security could come in and say, ‘We’re shutting this down,’” suggested Nick Honachefsky of The Fisherman magazine. The Empire Wind project planned by Equinor is located close to the busy shipping lanes to New York Harbor, he noted.

Equinor, Ørsted and EDF Renewables are all hoping to win contracts for at least part of New Jersey’s first 1,100 MW, and they are already engaged with the commercial fishing industry and its intense worry that trawling, scallop dredging and other mobile gears will be curtailed.

“We are committed to co-existence,” said Stephen Drew, whose Sea Risk Solutions LLC works with the undersea cable industry and has been hired by Equinor to help as a fisheries liaison. “We want the mobile gear to be able to continue working there.”

Equinor is working with fishermen, a gear designer and net builders to study how the commercial boats could work inside the arrays and use that information in site design, said Drew.

For recreational fishing boats, “frankly I see few issues,” Drew added. “You shouldn’t bump into the turbine, or tie up to it.”

Providing tie-up points close to turbines might be a good idea, suggested angler Tom Siciliano: “At some point when more boats of varying abilities get out there boats are going to start hitting these windmills.”

“We have not yet had a collision in 25 years with one of our turbines,” said Kris Ohleth, a New Jersey native and senior stakeholder relations manager for Ørsted. “Of course I try to explain to my Danish colleagues that New Jersey is different.”