A four-year study of planned wind energy areas off the East Coast found that building and operating offshore wind energy arrays could affect some of the region’s most commercially valuable fish species.

The report by scientists with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration was written to help the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management to evaluate development plans for eight offshore wind energy leases issued by the agency.

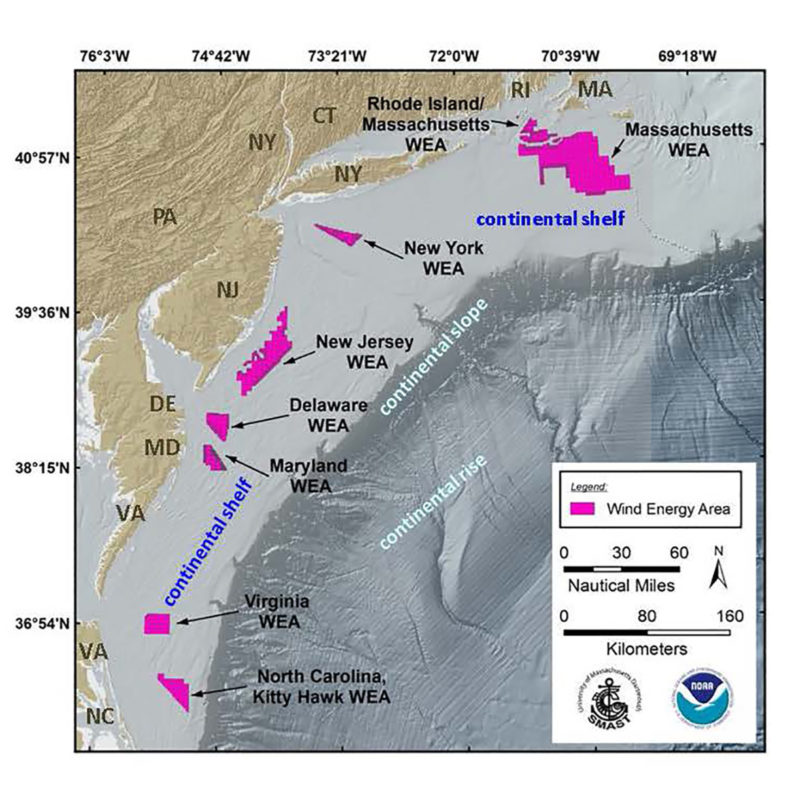

Those areas, extending from the largest proposals to date off southern New England to North Carolina, represent just about 2.7% of what NOAA Fisheries defines as the Northeast U.S. Continental Shelf Large Marine Ecosystem, according to the report. Since then four more leases have been issued, for a dozen proposed wind developments in all.

“While the extent of the WEAs (wind energy areas) may appear small in comparison with the entire system, it is the largest pre-planned anthropogenic (man-made) development in the coastal ocean in this region,” the authors note. “Further, the LME is not homogeneous, so that the effects of WEA development can potentially have impacts out of proportion to its small size.”

Jen McHenry (foreground) and Heather Welch (background) measuring beam trawl catch aboard NOAA research vessel Henry Bigelow. NOAA Fisheries photo/Vincent Guida.

High on the list of potential impacts are habitat for black sea bass and Atlantic cod, which use patches of gravel and rougher bottoms on the largely sandy outer continental shelf. Sea scallops, the highest dollar value species on the East Coast, are found in all the WEAs with the most significant overlaps in New England, according to the report.

Surf clams and ocean quahogs – harvested for canned chowder, frozen clam products and other processed seafood – are found in most of the WEAs. Advocates for the sea clamming fleet have insisted BOEM needs to set minimum distances of two nautical miles between wind turbine towers or their boats will effectively be shut out of fishing those areas.

The study was conceived in 2013 by researchers Vincent Guida, Jennifer Sampson and Rich Langton at the NOAA James J. Howard Marine Sciences Laboratory at Sandy Hook, N.J. j. in Sandy Hook, NJ, conceived a project to study bottom habitat in these wind energy areas. They proposed the project to BOEM, which was in the early stages of preparing the first East Coast leases, and the agency agreed to fund the project.

“Large areas of fisheries habitat in the ocean would be involved and potentially impacted by these WEAs and the resulting construction and operation of wind facilities,” said Guida, who led the project and is now chief of the Howard lab’s Ecology Branch. “We felt BOEM should know what is there now, what environmental issues and potential impacts there might be, before these areas are developed.”

In all 10 scientists with the NOAA Northeast Fisheries Science Center worked on the report, with additional contributors from the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth., Mass., and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution on Cape Cod.

The team reviewed previous research and data collections that had been conducted in the WEAs, and mounted their own cruises on NOAA research vessels to collect and analyzed about 1,000 new samples and related data.

The work went into a “contemporary and comprehensive benthic, or bottom, habitat database that can help provide insight into environmental issues,” according to NOAA officials.

Historic data about the region’s fish populations goes back decades into the 20th century. But the study authors acknowledged upfront that there have been dramatic changes off the East Coast, influenced by factors from fishing pressure to climate change.

“Thus, we restricted the use of the historic database to the period of 2003 to 2016 to avoid the some of the major shifts in the ecosystem prior to that time,” the authors wrote. “We felt this would provide a more realistic view of the current state of each WEA than the use of all the data while providing enough data for a representative sample. “

Building turbines arrays in that ecosystem has the potential for new changes – one that could affect fish stocks that need “structure” of rocky bottom, gravel or shell, the report says.

“In the southern New England and the southern mid-Atlantic subregions, where sandy sediments are the overwhelming dominant type of bottom, the structured habitats preferred or required by Atlantic cod and black sea bass can be a stock limiting ecological resource for those species,” the report says. “Hence, their disturbance becomes a management issue.”

That database, housed at the Howard lab, gives BOEM “a baseline for evaluating the potential impacts to benthic marine resources during offshore renewable energy facility construction, operation, and decommissioning,” according to NOAA.

Their report on the project, Habitat Mapping and Assessment of Northeast Wind Energy Areas, was published in December 2017 and is available online. The group’s work was delivered and published in December 2017, but NOAA is publicizing the report this week, at a time when BOEM and wind developers are in intense discussions with the seafood industry.

Advocates for the commercial fishing industry insist that BOEM and developers do more to mitigate spatial and environmental conflicts with the fleets, and BOEM this month put wind companies on notice that they will be required to set aside vessel transit lanes through their southern New England leased areas.

At its annual meeting, the American Fisheries Society devoted a day-long session to the potential impacts of offshore wind energy development. The consensus at that August gathering in Atlantic City, N.J., was that much more study and developing baseline science is a critical need as the industry prepares to set up in U.S. waters.

The NOAA report summarizes each of the eight wind energy areas in detail, and expresses concerns about how construction and operations could disturb the environment. The researchers address topics ranging from bottom water temperatures, bottom topography and features, types of sediments and ocean currents, to animals that live in and on top of the sediments and in the water column in that area either seasonally or year-round. Some examples include:

The Massachusetts WEA, covering about 743,000 acres of flat, primarily sandy bottom south of Cape Cod, has been divided into four lease areas. Forty managed fishery species were found ranging from year-round catches of little skate, winter skate, and silver hake to seasonal species including longfin squid, scup, spiny dogfish, and Atlantic herring. Possible habitat disturbance from offshore wind construction and operations include concern for black sea bass (warm season), Atlantic cod (cold season), sea scallops and ocean quahogs (both year-round).

The Rhode-Island-Massachusetts WEA covers about 165,000 acres at the southern end of Rhode Island Sound adjacent to the northeast corner of the Massachusetts WEA. It is divided into two lease areas and includes many of the same species found in the Massachusetts WEA, with the addition of ocean pout and yellowtail flounder during the cold season.

The New York WEA covers about 79,000 areas of flat, almost entirely sandy bottom south of western Long Island and is a single lease area. Possible habitat disturbance raises concern for black sea bass and longfin squid egg mops, sea scallop, surf clam and ocean quahog.

The Delaware WEA, about 96,000 acres southeast of the mouth of Delaware Bay, is also a single lease area. It has a 1,000-acre artificial reef known as the Fish Haven and at least one natural blue mussel reef. Mussel reefs and communities dominated by hard and soft corals are of concern as important habitat for black sea bass.