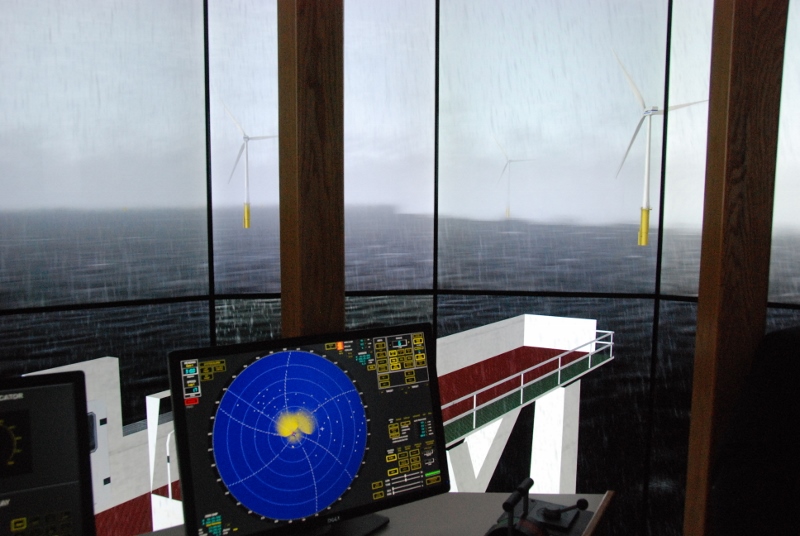

Off to starboard, a row of towering wind turbines spun slowly amid low fog and showers, casting flickers on the bridge radar screen.

“This is an 18,000-TEU containership,” explained Eric Johansson, a professor of marine transportation, standing at the Bouchard Transportation bridge simulator at the State University of New York Maritime College in the Bronx, N.Y.

“As these rotors spin, they will create some radar images, so we show that,” said Johansson, as an offshore service vessel emerged from the murky computer simulation, newly built by Kongsberg Digital Simulation Ltd.

The scene imagines a not-too-distant future, perhaps as soon as 2022, after Statoil builds its planned offshore wind energy array between approaches to New York Harbor.

“So this is going to be different,” said Johansson, a third-generation New York tugboat captain, as a visitor tried his hand at maneuvering an articulated tug-barge near the row of the simulated towers. “I don’t know how this will all fit, or how it will work out.”

At SUNY Maritime’s annual towing industry conference, mariners heard about those plans — and even bigger proposals for New York to get much more wind energy out of the ocean by 2030.

Professor Eric Johansson of SUNY Maritime College shows the new wind farm navigation program in the Bouchard tug and barge simulator. Kirk Moore photo.

“The big takeaway is there’s a huge opportunity with offshore wind for the maritime industry and manufacturing,” said Greg Matzat, an advisor to the offshore wind industry who worked with the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, the agency leading New York’s ambitious offshore wind planning.

“There’s a lot of users out there,” Matzat added. “Industry wants to work with everybody here to minimize impacts … one of the reasons we know this can be solved is they do it in Europe.”

The Coast Guard is in charge of navigational risk assessment, and working on an integrated approach that anticipates large wind arrays from southern New England to South Carolina, said Lt. Cmdr. Josh Buck of the Coast Guard’s New York Sector.

“It can ultimately cause large effects if those cumulative effects are taken into account,” said Buck. That effort to establish an overall routine system, allowing for federal offshore wind energy lease development and adequate fairways for shipping, is anticipated to take two to five years, he said.

“It is in a planning and analysis stage now,” said Buck, and maritime interests should expect to soon see a “call for information” to help the Coast Guard in that process.

A digital chart in the Bouchard bridge simulator shows the planned Statoil wind power array (dark blue triangle) between traffic separation ship lanes near New York Harbor. Kirk Moore photo

The federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, which oversees offshore wind development, held a meeting in Washington, D.C., last week with the Coast Guard, wind developers and other interested groups, said Buck.

BOEM ultimately calls the shots on approving the location and configuration of offshore wind developments, but the Coast Guard is “the proponent for navigational safety,” he said. If something “really poses a risk, we’re going to do our best to provide that feedback.”

Clearances and setbacks from shipping routes are in that discussion, and distances of two nautical miles along traffic separation schemes, and five nautical miles at their entrances, have been starting point guidelines.

“Each of those will be looked at on a case-by-case basis,” said Buck. “This involves so many stakeholders…we’re going to have to work through it together.”

NYSERDA is assembling technical working groups, including maritime interests and people from the region’s commercial and recreational fishing industries, to advise on those siting issues.

The Bouchard simulator and Kongsberg’s new software will help both mariners and future wind farm operators to see what they will be dealing with. In addition to simulating navigation around wind arrays, Kongsberg is working on programs that model wind farm installation and crew service vessels, said Clayton S. Burry, the company’s vice president of Americas sales.