In March 2022, a collection of international teams embarked on an expedition to locate and document the wreck of HMS Endurance, the famed ship used by Sir Ernest Shackleton in his failed 1914-1917 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. The vessel had been lost to the Antarctic waters of the Weddell Sea for over a century. Using advanced subsea technology, the subsea team, led by Nico Vincent [Deep Ocean Search (DOS)] and John Shears (Shears Polar), found the ship resting on the ocean floor, 10,000' below the ice.

The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition aimed to cross the Antarctic continent from coast to coast via the South Pole, but the expedition was thwarted when Shackleton’s three-masted barquentine, the Endurance, became trapped in ice, leading to a dramatic survival story as the Anglo-Irish explorer and his crew endured extreme conditions. All men were ultimately rescued, but the Endurance was crushed and sank, not to be seen again for more than 100 years.

The Endurance22 project, funded by the Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust (FMHT), aimed to locate the long-lost wreck and conduct a non-invasive study. The teams based their search on a 1915 journal entry by Capt. Frank Worsley, who, on the day of the sinking, had to delay taking sextant readings due to overcast skies. The 24-hour pause meant his calculations provided an estimate, rather than precise coordinates of the ship’s final position.

“This project was a decade in the making, beginning in 2012 when the project’s anonymous benefactor met with Trustee Mensun Bound in a London coffee shop,” an FMHT spokesperson told WorkBoat. “The initial plan was to launch the search in December 2013, but securing a suitable icebreaker proved impossible. Over the years, numerous experts advised on how to proceed, refining plans for both the first and second expeditions until the conditions were finally right in 2022,” they said.

Jérémie Morizet, subsea engineer at DOS, detailed the company’s mission preparation to WorkBoat.

“The project involved three years of management and planning led by Nico Vincent. Then we had a period of, let’s say, six months of onshore prep,” Morizet said. “During this time, we had to go to the factory of Saab’s Sabertooths to oversee the [autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV)] survey payload integration and assist with configuration. We then conducted trials before transferring the vehicle to the south of France, where we tested it at depths of 3,000 meters (9,843').

“After the onshore phase, we mobilized in South Africa, which took about two weeks to gather all the equipment that were air freighted from different parts of the world to fit everything on board, to connect everything, and then after … we finished overall integration as we were sailing underway,” he said.

The Endurance22 mission called on the S.A. Agulhas II, an icebreaker owned by South Africa’s Department of Environment, Forestry, and Fisheries that served as a central operations hub for eight teams on board. The 440'x71'x35' ship carried a full South African crew of 65 managed by African Marine Solutions Ltd., along with an expedition team of 45 archaeologists, oceanographers, meteorologists, drift prediction experts, and ice scientists. Additionally, a subsea operations team of 17 including 10 subsea experts from DOS were on board. While the Endurance22 mission focused on locating the wreck, other teams aboard the vessel conducted separate research efforts.

“Picking the right ship for the expedition was not just about finding an icebreaker — it had to be one of the very few in the world that could handle the extreme conditions of the Weddell Sea,” FMHT said. “Only a handful of vessels are tough enough to operate there. The S.A. Agulhas II is a Polar Class 5 icebreaker, meaning it can smash through ice up to a meter (3.3') thick while still cruising at five knots. What was key for the Trust was the quality of the research facilities on board. On top of that, the ship had already proven itself in Antarctic missions, including reaching the Endurance’s last known location back in 2019,” the Trust said.

Agulhas II is powered by four Wärtsilä medium-speed diesel engines and a diesel-electric propulsion system. Two Converteam 6,000-hp motors drive 14.8' Kongsberg controllable-pitch propellers, while Rolls-Royce bow and stern thrusters enhance maneuverability; useful features when operating in extreme weather conditions. The vessel’s 16-knot maximum speed and 15,000-nautical-mile range ensured operational flexibility for the 50-day expedition.

After departing Cape Town, South Africa, on Feb. 5, 2022, it took the Agulhas II 13 days to arrive on site.

SUBSEA OPERATIONS

Central to the mission was the Sabertooth drone, which Morizet described as a hybrid system that can behave as a classic remotely operated underwater vehicle (ROV) or like an AUV. “You can switch between the two modes pretty instantly, which makes it the perfect tool to make object search, or in this case, wreck search,” he said.

The Sabertooth’s ability to transition between surveying and inspection streamlined operations that typically require separate vehicles. “With the Sabertooth, you can go from one mode to the other,” Morizet explained. “In the standard subsea operations, you first make your survey with a towed vehicle or an AUV, and then only after, you can come back with the ship to deploy an ROV to check what is the target that you’ve picked up. So, it’s much more time-consuming. It’s much more expensive,” he said.

The Sabertooth was equipped with advanced survey and imaging technology for the mission. It carried an R2Sonic Sonic 2024-V multibeam echosounder for high-resolution bathymetric mapping and a Sonardyne Gyro USBL LMF for acoustic tracking and positioning. Navigation, speed, direction, and motion data were provided by the Sonardyne Sprint NAV system, and the Voyis Imagery Insight Pro conducted photogrammetry, generating 3D models of the wreck using underwater laser scanners and imagery. Additionally, the EdgeTech 2205 system collected side-scan sonar imagery, sub-bottom profiles, and bathymetric data to aid in the survey.

Operating in Antarctic waters posed unique challenges, especially in the presence of shifting sea ice. According to Morizet, once the icebreaker stopped to deploy the Sabertooth AUV, the surrounding ice began to carry the Agulhas II away at speeds of up to one knot or more. “As soon as you stop the surface vessel to deploy the vehicle, the ice just captures you, like the Endurance, and takes you away,” he explained. His remarks parallel those from Shackleton crewmember Thomas Orde-Lees, who described the ice-trapped Endurance “frozen like an almond in the middle of a chocolate bar.”

As the icebreaker drifted, the AUV continued its survey within a designated search box, creating a complex situation where the surface ship and the subsea vehicle moved independently, requiring continuous adjustments to the survey pattern.

Morizet credited ice drift specialists from the German-based Drift+Noise Polar Services, who utilized a drift-prediction model to anticipate pack ice drift directions, allowing the team to draw the best survey line pattern in real time.

“It is a model, so it’s not always true,” he admitted. “The final survey pattern we had on seabed went from nice and clean parallel survey lines to a kind of weird patchwork with survey lines going in different directions and different shapes; S-shapes, U-shapes. So, it means that we had on bottom to adapt our survey pattern, depending on the direction of the surface vessel. It was a complex, complex game.”

Speaking to the AUV deployment and operations, Morizet said, “You preprogram your mission. It’s a very versatile vehicle, offering different modes of operation … A fantastic feature of this AUV, I would say, is that it can fly in any position, like a fighter aircraft … So you can … roll it 45 degrees and stabilize the position and run it like that, or you can even run it upside down if you want to scan under the ice.”

To prevent excessive tension on the fiber-optic tether, the team had to constantly pay out cable, up to five miles at one time. “You don’t want to maintain a strong traction on the vehicle, because otherwise it will go away from the search box,” Morizet noted. However, as more cable was deployed, drag from ocean currents increased.

“At some point, even though the fiber-optic tether is very thin, it creates a drag … and you start to feel on the Sabertooth that you have another consumption of battery, and the progression slows down,” he said. “It’s a trade-off between the current, the battery, etc. Sometimes the battery life forces you to recover the vehicle because there is no more battery. And sometimes, the drag is becoming so, so strong that it’s hardly workable,” he said.

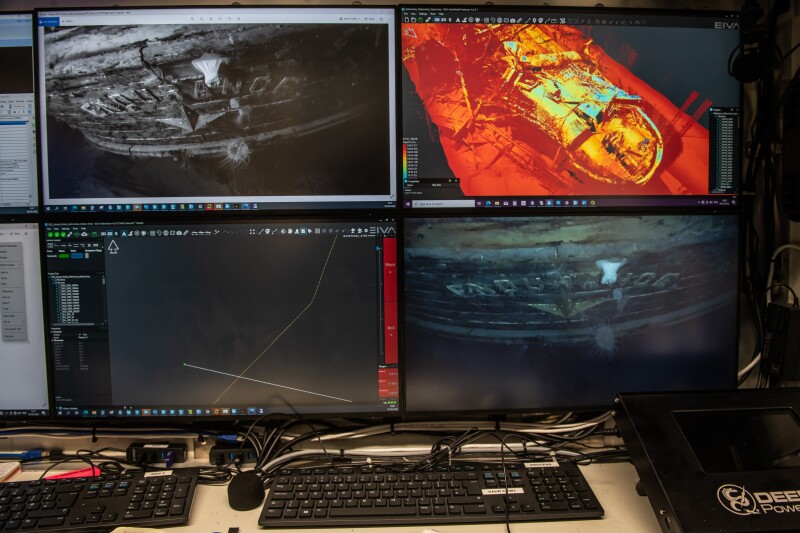

The fiber-optic cable is a two-way data street between the control room and Sabertooth, carrying commands from the ship to the AUV and returning information, including from its side-scan sonar, described by Morizet as the primary tool for detecting shipwrecks due to its ability to cover large search area. To effectively monitor this incoming data, the control room aboard the Agulhas II was divided into two desks: one for the pilots and another for the survey team.

The AUV’s navigation relied on an inertial navigation system integrated with an ultra-short baseline acoustic positioning system. “The surface vessel sends an acoustic interrogation to the vehicle, which then replies. From this two-way travel, we determine the position of the subsea vehicle,” Morizet said. This data was transmitted through the bi-directional fiber-optic tether, however, in cases where the fiber was lost, the team used an acoustic telemetry system for emergency recovery.

When the tether breaks, which happened a few times during the expedition, “the vehicle is still alive because it still relies on its batteries, but we don’t have the command, neither the feedback,” Morizet said. “And so, in that case, we could take control of the vehicle using what we call a subsea telemetry system. It’s a very slow communication system through water, but it allows at least to bring the vehicle back home,” he said. By sending acoustic commands and receiving acknowledgments, the team could regain control and guide the vehicle back to the surface vessel.

To help mitigate fiber breaks caused by sea ice, DOS designed a ‘fish float’ that allowed the fiber optic cable to move with the flow, rolling around ice blocks rather than being crushed by them. “We were surprised we had so few breaks, because in such an environment where there is so much ice around that wants to crush the fiber-optic through the water interface, were just expecting to have much more damage than that,” he said.

After 20 days of navigating strong currents and overcoming operational constraints, the Sabertooth’s side-scan sonar detected a reading emerging from the ocean floor. The control room erupted in shouts as the team confirmed the identification of the shipwreck they had been searching for.

The team then switched the Sabertooth to inspection mode to survey the wreck, and using photogrammetry from the Voyis Insight Pro, they captured high-resolution images of the Endurance’s transom, hull, and deck, which contained preserved crew boots, intact tile patterns, blocks, pulleys, and other artifacts left on the vessel. The Sabertooth’s enhanced maneuverability also allowed for scans of the lower hull sections that a standard, flat-positioned vehicle would have missed.

FMHT spoke to the mission’s success. “We are incredibly proud of what was achieved — not just in finding Endurance, but in sparking curiosity and interest in the story of Shackleton, the wonders of deep-sea exploration and the challenges of working in one of the most extreme places on Earth.”

Reflecting on the experience, Morizet said, “Meeting Antarctica is already something that changes every man and woman on board. You hear about it in the storytelling of Shackleton and everything, but when you really experience it, you truly understand what they endured. You really want to come back one day. So that was just fantastic.”