The mega-population centers that attract offshore wind energy companies to the U.S. East Coast are spread farther along the Gulf of Mexico. But the Gulf’s immense industrial appetite for energy is making it look like a good bet for the wind industry’s future.

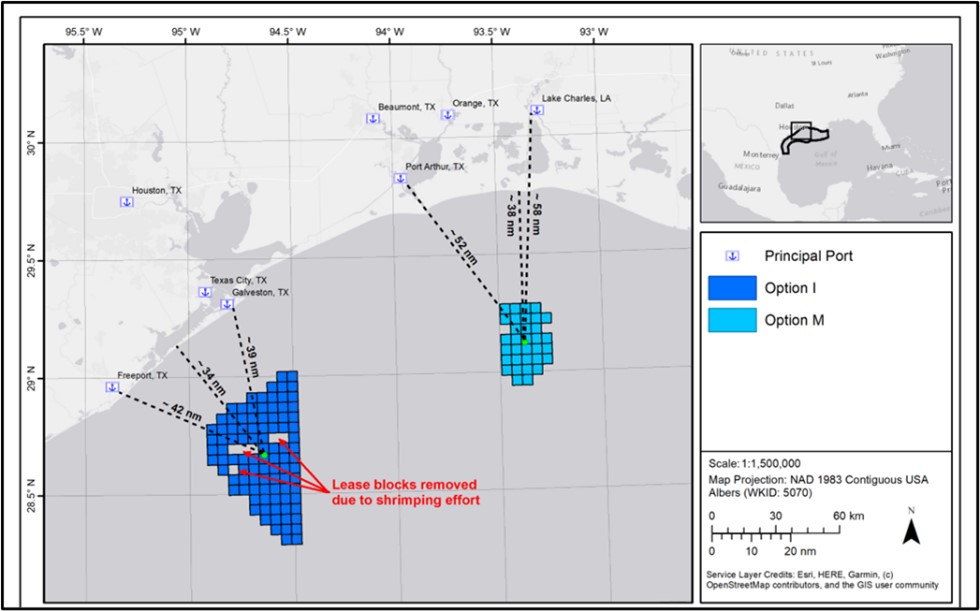

Two wind energy areas – one 24 miles off Galveston, Texas, with 508,265 acres, and another 56 miles south of Lake Charles, La., with 174,275 acres – are the first laid out by the Bureau of Offshore Energy Management.

The Gulf states’ industry, with its deep experience in offshore energy work, is already involved in the East Coast wind projects. Some 20 percent of those contracts have gone to Gulf states, according to the non-profit Business Network for Offshore Wind, which says half of its recently joined members are from the region.

There are now around 1,200 offshore wind supply contracts in the domestic U.S. market, said Liz Burdock, CEO and president of the Business Network for Offshore Wind during a Dec. 2 update at the International WorkBoat Show in New Orleans. Some $12.7 billion invested in the U.S. so far includes $5.38 billion paid to BOEM for leasing.

The investments include upgrades and new construction at 21 ports on the East Coast, and “I don’t think we’re done on the East Coast by any means,” said Burdock. To serve those projects 23 vessels are now under construction or in retrofit, she said.

The industry’s top vessel needs are wind turbine installation vessels, cable laying ships, feeder barges to carry turbine components, service operations vessels and rock laying ships to put down armoring around turbine foundations. Looking at the pace of planned U.S. projects and the supply of vessels, 2026 could be a year of bottlenecks, said Burdock.

Longtime offshore service vessel operators at a Marine Money finance forum Nov. 30 in New Orleans said they need more assurance that the wind business will be profitable enough before they make big commitments. Offshore companies and shipbuilders expressed the same sentiment at IWBS panel discussions, in a season when inflation and material costs have wind developers reconsidering their prospects.

But those sessions were packed, a clear indication of how Gulf region businesses are looking to offshore wind.

“It’s moving faster than I anticipated,” said Joe Orgeron, co-founder of 2nd Wind Marine LLC, Galliano, La., and a Louisiana state legislator supporting offshore wind initiatives.

Orgeron said he anticipated that Vineyard Wind’s 800-megawatt project off southern New England would need to be operational before other developers made big moves in the U.S. market. Now, Orgeron says, it is apparent that “we’re going to do this.”

“The job you’re going to do is virtually the same as what you’ve been doing,” Orgeron tells his colleagues in the offshore business. When wind power comes to the Gulf, it will drive “the energy addition” rather than a complete energy transition, he says.

“We’re still going to need plastics and hydrocarbons,” said Orgeron. Most energy in the Gulf “goes to high energy industrial processes” like plastics and fertilizer, making them ready customers for turbine projects, he says.