The federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management is preparing its New York offshore wind energy lease sale, after removing almost 2,000 acres of fish habitat.

The Cholera Bank, an undersea elevation that attracts fish – and fishermen – southeast of New York Harbor was trimmed from a final lease map issued Thursday by BOEM. The agency will put the remaining 79,350 acres up for lease sale to wind energy developers Dec. 15.

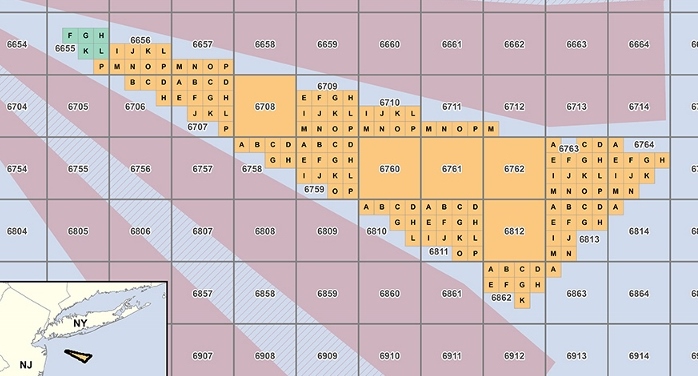

Roughly shaped like an elongated triangle with its narrow end closest to New York City, the New York Wind Energy Area starts 11.5 nautical miles south of Jones Beach, N.Y., and extends 24 nautical miles southeast. It contains five full lease blocks on the outer continental shelf (OCS) and 143 sub-blocks.

By vessel, the apex of the triangle is about a 29.5 nautical miles from the terminals at Bayonne, N.J. On charts, the blocks are tucked between the Traffic Separation Scheme (TSS) shipping lanes in and out of New York Harbor.

A compilation of AIS tracks in the separation lanes demonstrates BOEM’s thinking that a one nautical mile buffer between the TSS lanes and the wind energy area is sufficient for navigation. BOEM photo.

Some adjustments have been made after input from the Coast Guard and maritime interests, but BOEM believes a one nautical mile buffer between the TSS lanes and the wind energy area is sufficient for navigation, according to a revised environmental impact statement.

BOEM staffers reviewed years of Automatic Identifying System (AIS) records showing the tracks of vessels as they transited the separation lanes. The tendency for large cargo and tanker vessels to track closer to the inside edges of the lanes create an additional “de facto buffer” that reduces the danger of an allision with turbines, according to the statement.

Tradition holds that the name Cholera Bank refers to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when immigrant passenger vessels were quarantined outside the port to check for communicable diseases.

One criticism of the draft New York area map was that it infringed on the bank’s important fish habitat, a position taken up by the National Marine Fisheries Service. Removing it — cutting off the tip of the triangle by 1,779 acres — also helps meet the Coast Guard’s recommendation for wider buffer space at the western ends of the traffic lanes, the BOEM statement notes.

Commercial fishermen depend heavily on the area for squid fishing, and argued that the disturbance and noise of construction could destroy the fishery. BOEM was not buying that, pointing to the heavy ship traffic in and out of the port. But as a condition of the lease, a successful bidder will need to set up a formal liaison and communications system with the fishing industry, the agency says.

To prepare for bidding BOEM has qualified 14 companies as legally, technically and financially credible to develop the tract. The list includes homegrown U.S. ventures like Deepwater Wind LLC of Rhode Island and Fishermen’s Energy LLC from New Jersey. Two major European players based in Denmark and Norway that want to crack the U.S. market are in the running too: DONG Energy Wind Power (U.S.) Inc. and Statoil Wind U.S. LLC.

The nation’s sole commercial offshore wind energy project, a 30-megawatt array of five turbines in state waters off Block Island, R.I., was recently completed by Deepwater Wind. So far BOEM has awarded 11 leases in federal waters, opening one million acres on the continental shelf for future development.