Despite expectations of a looming oil market deficit, prices have remained surprisingly low. According to Rystad Energy, the oil market is projected to face a significant deficit, averaging 2.4 million barrels per day (bpd) for the remainder of the year.

Why aren't oil prices higher despite the expected market tightening? Rystad Energy suggests a combination of non-fundamental factors, lagging demand, and stronger-than-expected supply are at play.

Demand: is growth still as robust as we believe?In our Base Case, we forecast that oil demand will increase by 1.7 million bpd in 2023. This growth rate is relatively conservative when compared to other main forecasters.

Our growth forecast this year has mainland China (from the regional point of view) and jet fuel (from the product point of view) as the main growth engines.

Mobility data is a great indicator of the actual evolution of demand despite data by nature being volatile. The latest mobility data shows mixed signals. Global road traffic has fallen below 2019 levels in the last couple of weeks after remaining above those levels for more than three months.

Most of the decline seen recently is concentrated in China, Europe, and North America. China has been dealing with another wave of Covid-19 for the past month, which has kept some people voluntarily at home, albeit without any lockdowns. We expect the effect to be temporary.

Chinese crude imports also reveal an interesting element as they have remained very strong recently.

In March, imports reached 12.3 million bpd, the highest level in three years. In May, they reached 11.4 million bpd, which is 5% above the level seen in May 2022 and 18% above May 2021.These strong import numbers suggest oil demand remains solid; however, the caveat is that, at the same time, crude storage has been increasing in the last few months, which implies that demand is potentially lagging.

Supply: tight control by OPEC+ but have promises been broken?

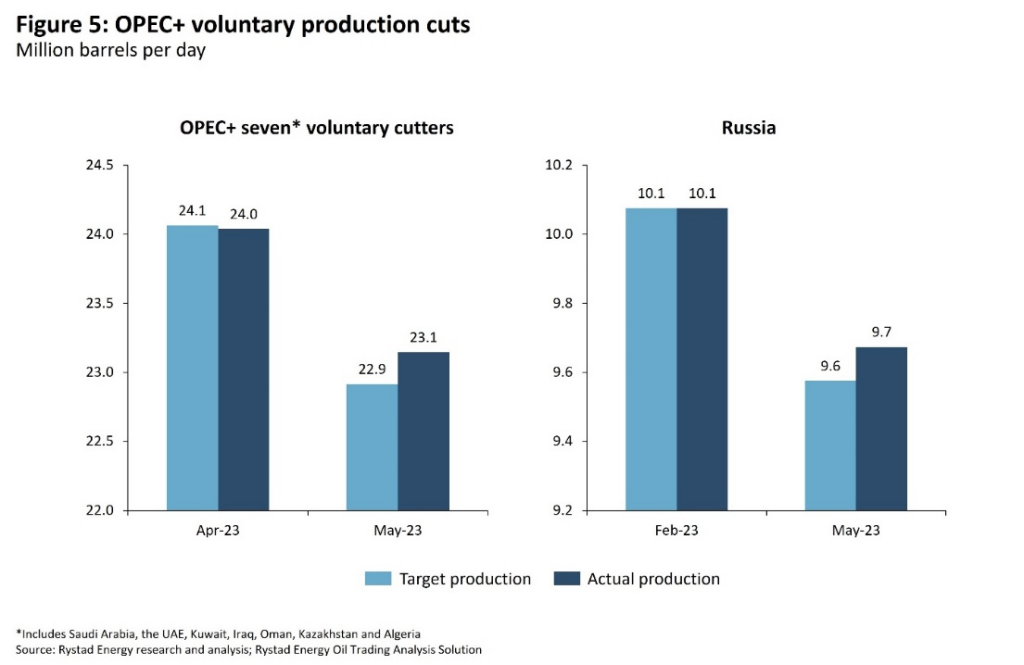

In April, seven OPEC+ countries, led by Saudi Arabia, introduced voluntary cuts running from May until December 2023 and amounting to 1.15 million bpd. Additionally, Russia announced in March that it will voluntarily reduce production by 500,000 bpd until the end of the year.

The latest production figures for May show something of a glass-half-full picture. Whereas output from the group of seven countries did drop last month, it was by slightly less than promised – while the promised cut was 1.15 million bpd, production declined by less than 900,000 bpd.

In the case of Russia, there is also a gap between actual and promised cuts in May – out of the announced cut of 500,000 bpd, production has declined but only by 400,000 bpd.

The mismatch between Russia's production decline and increased seaborne crude exports is significant and puzzling.Despite the announced cuts, exports have risen from 3.3 million bpd in February to around 3.5 million bpd in recent weeks.

The intriguing aspect is that if this ongoing disparity persists, with high exports and alleged production cuts, it could potentially lead to a significant shift in the supply dynamics and provoke a notable response from the rest of the OPEC+ group.While the likelihood of this occurrence is low, its potential impact on prices is substantial, which may be a contributing factor to the prevailing bearish sentiment in the market.

Moreover, opaque exports from sanctioned countries like Iran and Venezuela further contribute to supply uncertainty.Surprisingly, while expectations suggested a drop in Iranian crude exports, they have remained stronger than anticipated due to Russia's reduced reliance on the dark fleet tanker market.

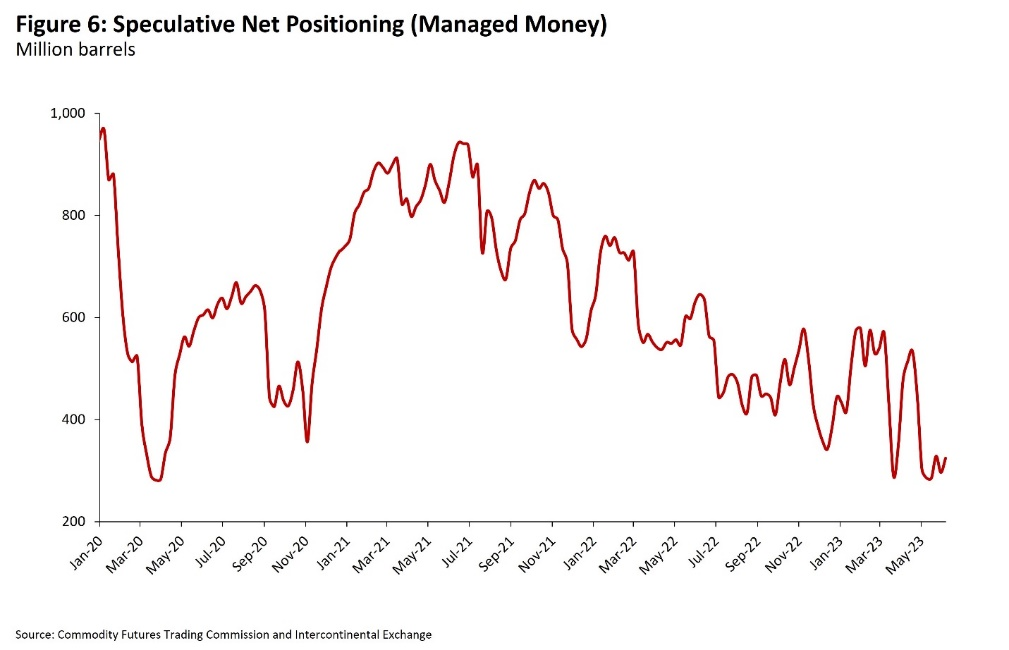

Non-fundamentals: are high inflation and high interest rates dragging oil prices? The recent underperformance of energy commodities compared to other asset classes is primarily influenced by the macroeconomic environment and asset allocation decisions.

High interest rates and inflation have driven a shift towards safer assets, such as cash and bonds, due to recessionary fears and financial uncertainty.

Previously, commodities, notably crude oil, served as an inflation hedge, but with inflation already peaked and declining, the appeal of this hedging strategy has diminished.

As a result, speculative positioning on the oil basket has plummeted, reflecting a low level of confidence in tight physical markets in the coming months.

Higher interest rates have had a direct impact on opportunity costs in the physical markets, leading to a decrease in the incentive to hold oil stocks, as observed in other markets as well.Global crude and condensate volumes in floating storage has declined from around 80 million barrels in January to less than 65 million barrels in April, its lowest level since early 2020, according to the IEA.

Will oil hit $90 per barrel any time soon?We believe that at some point in the coming weeks market fundamentals will drive the oil market. Upside price pressure will materialize soon.

However, downside risks include a potential failure to stimulate the Chinese economy and lower-than-expected discipline by OPEC+ in adhering to production cuts.

Despite these risks, we remain confident that significant upside price pressure will materialize in the second half of the year.

Jorge Leon is a senior vice president with Rystad Energy.